Health insurance applications that you put on your mobile phone or tablet are very convenient for monitoring not only your health plan, but also doctor appointments, lab results, and searching for health care providers. Built into these apps is software that tracks you, collect your data, and shares your data with other applications. They are building a profile of you, based on your behavior, to market other products and services to you.

First, I want to stress that none of the health insurance applications are sharing any personally identifying information (PII) or personal health information (PHI) that is protected under HIPAA regulations. However, they are gathering other data, that when matched with other information from your device, creates a clear picture of who you are. This is not a 2-dimensional picture, but one that is closer to a 3-dimensional model because it includes time and space. Some apps are collecting data from your phone as you travel to the store, visit relatives, or go on vacation.

Health Insurance Apps Are Collecting Your Digital Image and Monetizing It

You cannot see the behavioral data that these health insurance and other apps collect. Oddly, they own the data. They own the data you created by your behavior of clicking on a link, taking a walk around the block, reading about mental health tips on the app, or the time you spent with a counselor through the app. Overtime, without ever having a picture of you, these apps have developed a digital profile of you. While some apps say they never sell their data, the few I’ve reviewed all state they share the data.

Health insurance companies are pushing their mobile applications. Some insurance customer service representatives are telling consumers to download their mobile app to get information on claims. From the company’s perspective, the mobile app reduces the expenses of customer service for the health plan if everything goes through the app. The bonus for the health insurance companies is the behavioral data profile they can build on the user and then monetize the data in the form of advertising.

The Privacy Statements Outline How They Collect Your Digital Behavioral Data

Of course, if we can’t see the data the apps are collecting, how do we know they are collecting behavior data with their application? They spell it all out in their lack-of-Privacy Statement. My first review of data collection within the privacy policy is from the Sydney Health app used by Blue Cross.

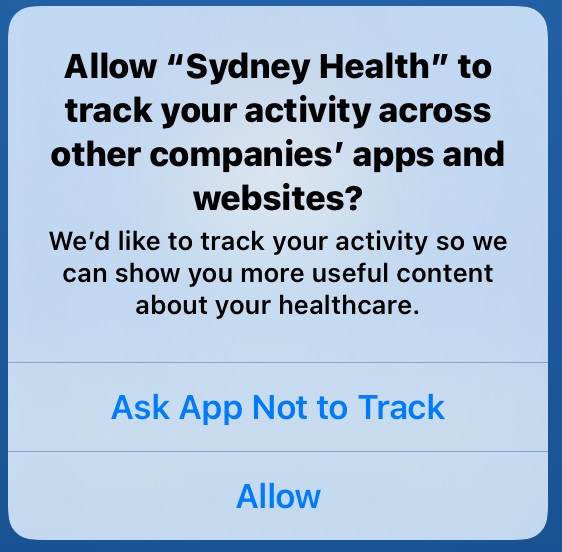

Before the Sydney app is even loaded on the mobile device it asks if it can track the user across multiple websites. But don’t worry, even if you opt out of tracking, they will still collect your data.

Many apps will put cookies on your device to facilitate the collection of data. However, the health plan app is a giant cookie sucking all or your personal behavioral data as you click on websites, interact with other apps, or check your emails at a café out of town.

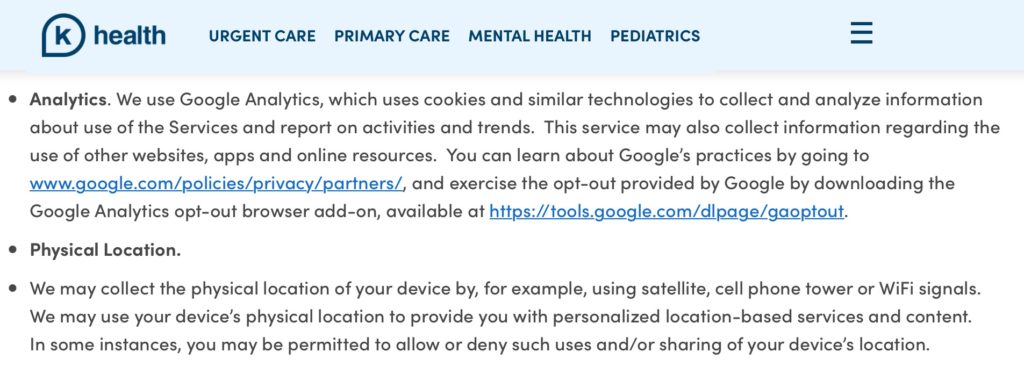

Another source of data that helps pinpoint your location is the IP address, which the app collects. The IP address can give general location data. This is helpful if you turn off your geolocation tracker on your phone.

The apps will use mushy descriptions like quantitative user information to soften the reality that they are extracting your information for their monetization. Note that the Sydney app states they do not sell personal information such as PII or PHI. All the other data they collect on you is on the table to be shared. They alert the user who may read the privacy statement that they work with third parties for the ultimate purpose to customize content and advertising. That means they, and others are generating a profile of the user, and when that specific device surfs the internet, some of the ad delivery systems can read the profile and deliver targeted ads. Advertisements uniquely suited to a person’s interests have a higher click-through-rate. Higher ad clicks equal higher revenue for the system delivering the ad.

Many of the apps just ignore the ‘Do Not Track’ option or signal from an internet browser. It’s not that they can’t stop tracking, they choose not to because there are no penalties for ignoring the signal. Also note the implicit threat in the first paragraph. If you don’t opt into all of the data gathering features, the app may not work correctly.

Health Apps Sharing Data With Other Health Apps for Advertising

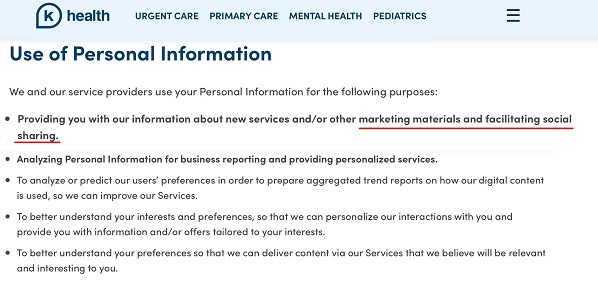

Linked to the Sydney Health app is another health care provider app called K Health. If you use some of the health care services offered through Sydney, you are being directed to this K Health app. K Health is another app that extracts your data, develops a profile of you, and keeps it forever.

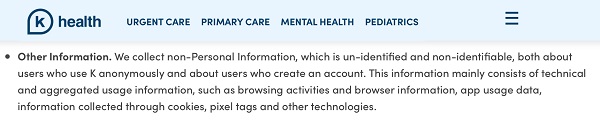

K Health is a little more descriptive in their privacy policy about the methods and collection of your personal data. Some of the methods for building a profile on the user is through the browsing activities, browser information, app usage data, cookies, pixel tags and – ominously – other technologies.

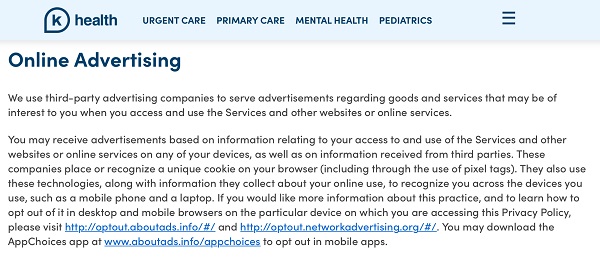

Like the Sydney app, the K Health data gathering is being used to monetize your profile and deliver marketing materials to you. What is a little creepy is that they state they analyze your personal information for business reporting and providing personalized services. But the element that describes where the whole behavioral surveillance industry is moving toward is the analysis and prediction of an individual’s decisions. Let me underscore, the goal is to aggregate enough data on you in order to predict what you want, when you want it, and where you want it from.

K Health spells out the other information they are aggregating on your profile that has nothing to do with providing health care services, such as demographics. While they state the aggregated data does not identify you by name, you are identified by a number, and the profile attached to the number is passed around to other apps. The demographic data is key to painting this digital portrait of you.

The three-dimensional profile these apps are creating of you are greatly facilitated by location data. Even if you have tracking and location IDs turned off on your phone, if you check your phone on the road, the wi-fi spot or cell tower in many instances can provide general location data. They know when you visit your relatives in another state and how often you travel there.

Bottom line for these applications, revenue from online advertising using your personally extracted data.

Most of the apps will have a general statement absolving them of any tracking or data gathering by third party apps they may interact with. In short, no one is responsible for anything, but they get to keep all the data rendered from your life.

When Oscar Health plans came on the market several years ago, their focus was delivering customer service through their mobile app. From the Oscar privacy statement, they are up front about collecting your data when you use their application, which can almost be the only way to get information from Oscar.

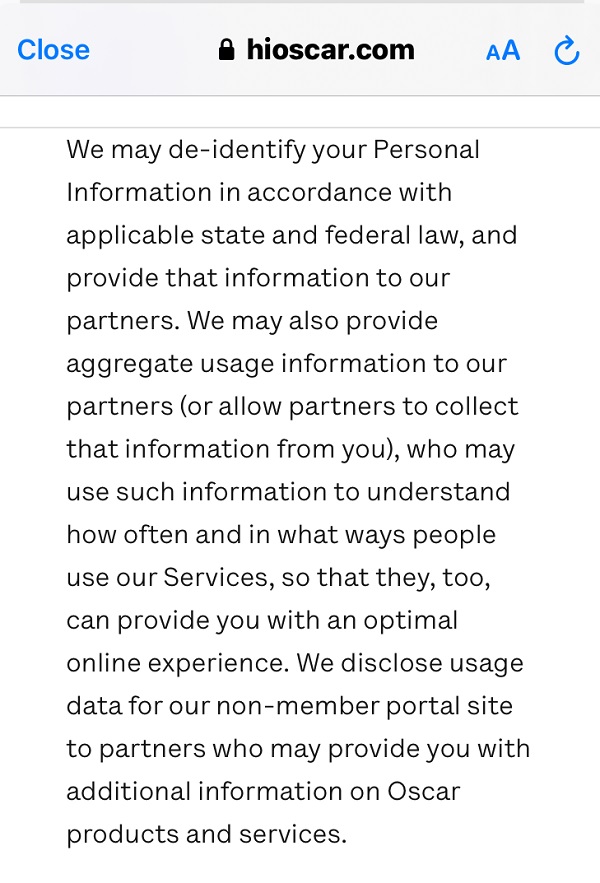

Supposedly, Oscar is stripping out any PII or PHI when they share your data with business associates and partners. However, the information is still being pushed to other entities to serve you advertisements.

Oscar Owns You

Even if Oscar goes out of business or is sold, your data profile is still one of their assets and it can be transferred to another business. They are taking the picture you created, declaring their ownership over it, and treating it like an asset they own, forever. You are now part of their balance sheet.

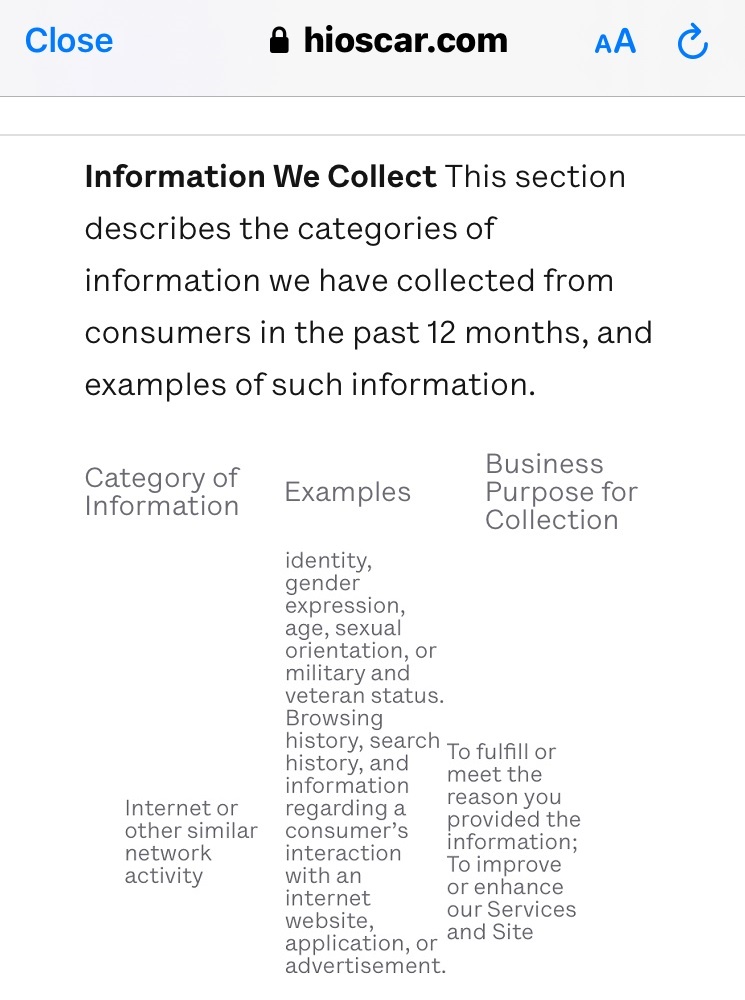

Oscar provides a long list of identifiers they collect on you. Some of the information is protected by a variety of laws, but most is not. Note they gather information on browsing history, internet searches, consumer interaction with any website or advertisement. This extraction of your online behavior is characterized as improving or enhancing their services and website. In reality, the big reason for the surveillance on you is to monetize your digital profile.

Oscar states they have not sold your data in the past 12 months. That does not mean they have not shared it with one of their investors, business associates, or mysterious third parties.

The extraction, storage, and manipulation of your personal online data is akin to the wild west. There are few rules in this relatively young industry and what rules there are, the app gleaners ignore until they are caught violating the law. You can’t see the digital portrait you have created by your own actions on your mobile device and captured by the health insurance apps. In a sense, they own your image. Usually images you create are protected by copyright laws. In this new industry of digital surveillance and capture, you don’t own your own image.

To learn more about this digital surveillance and the extraction of your personal information, refer to Shoshana Zuboff’s The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. The book is expertly researched and written. Zuboff outlines, in depth, how search engines, such as Google, quickly understood the value of digital exhaust or behavioral surplus, began capturing it and monetizing it in the form of advertising back to the creator: you.