Sacramento resident Scott Davis offers recommendations on how to stabilize and improve Obamacare.

Lots of people have suggestions on how they think the Affordable Care Act should be fixed. But rarely do they put their recommendations in writing with rationales to support their suggestions. Sacramento business consultant Scott Davis has put his recommendations and rationales down on paper for elected representative to read and ponder. You may not agree with all of Mr. Davis’ recommendations, but at least he is trying to provide recommendations to fix Obamacare from a consumer’s perspective.

WAYS TO IMPROVE THE AFFORDABLE CARE ACT

By Scott Davis

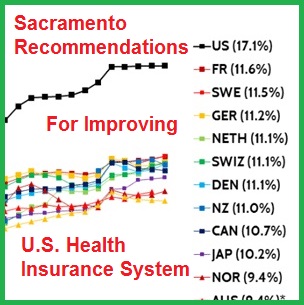

The United States spends far more as a percentage of GDP than other countries and has poorer outcomes on most other countries. The U.S. life expectancy of 78.8 years ranks 27th out of the 35 countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Among those countries it has the fourth highest infant mortality rate, the sixth highest maternal mortality rate and the ninth highest likelihood of dying at a younger age from a variety of ailments, including cardiovascular disease and cancer. A compelling argument can be made that the structure of our health insurance system problems with healthcare markets are key causes.

Health Care Spending as a Percentage of GDP, 1980 – 2013, showing how the U.S. outpaces other industrialized nations.

Source: “U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective” Commonwealth Fund (2015)

In September the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education Labor & Pensions is expected to hold hearings regarding reforms to the Affordable Care Act to consider changes that can be made to lower premiums and increase choice. Below are two sets of recommendations designed to accomplish those goals. The first set describes modifications to our insurance system and the second describes changes that can be made to lower healthcare costs as a whole.

Suggestions for Lowering Health Insurance Costs

- Repeal the employer mandate for all companies (regardless of size) and replace it with a payroll tax for all companies that do not provide insurance. The proceeds from that tax should be allocated to vouchers given to the employees which they can use to purchase health insurance or fund health savings accounts. Furthermore, employees should be given the option of opting out of employer-provided insurance in exchange for a comparable health insurance voucher.

Rationales: Requiring employers to provide insurance to their employees has two major negative impacts: 1) it imposes an administrative cost on employers and 2) it limits options for employees. Most businesses don’t have particular expertise in health insurance and the requirement that employers provide health insurance requires them to devote resources into evaluating alternatives, negotiating with insurance companies, and maintaining health insurance accounts. Many businesses lack the expertise to make the best health insurance decisions for their employees. For many businesses, it would be cheaper and less resource demanding just to pay a tax that corresponds to average actuarially fair insurance. In addition, the current mandate encourages employers to game the system by cutting back on the hours employees work or the number of employees they hire to avoid the health insurance requirements. This can be harmful to current and potential employees seeking full-time employment. Eliminating this requirement would mitigate arguments that the ACA is a “job killer.”

Furthermore, employer-provided insurance limits the health insurance options of employees. They are forced to accept the plan(s) negotiated by their employer which limits their choices. It also means that changing employers often necessitates a change in insurance coverage as well as a change in doctors and healthcare providers. As a result, many employees can feel “trapped” in a job because of their desire to retain their doctors and health insurance. Furthermore, some employers regularly change plans and carriers leaving employees with different benefits and providers. While employees like group coverage they are finding that they frequently must change plans because the company has switched carriers to reduce costs. I personally believe that there should be no association between employer and health insurance and note that current system is an outgrowth of a time when wage controls forced employers to include health insurance as one way to compete for employees.

2. Retain the individual mandate but have the tax penalties go to vouchers that can be used by the non-insured only to purchase insurance or fund a health savings account. I would suggest a penalty on the order of 10% of income up to a cap that corresponds to actuarially fair insurance premiums for the individual’s age. Subsidies should be provided to those people for whom this penalty will not cover actuarially fair insurance that are sufficient to cover the cost difference.

Rationales: Health insurance markets fail dismally when people who believe that they are healthy are allowed to opt out of buying insurance or are allowed to buy “skinny” plans that provide little effective coverage. The result is a pool of people seeking insurance who either (often correctly) perceive that they are at high risk or have sufficient incomes and are highly risk averse. The result is a risk pool with above-average risk and thus above average cost. Insurance companies know this and will raise premiums accordingly, discouraging even more healthy people from getting insurance. The result of this “adverse selection” problem is high premiums and limited coverage. The problem is magnified if insurance companies are required to issue insurance to people who have pre-existing conditions. This provides an even greater incentive for people who are currently healthy to defer obtaining insurance until health complications arise. The result is an even smaller risk pool with even higher premiums. Imposing penalties on people who choose to begin coverage after a time gap (such as a premium surcharge or a lag before coverage begins) provides a further disincentive for healthy people to begin coverage due to the higher initial costs or reduced initial benefits. Plans imposing deferred penalties with an uncertain financial impact will provide a much weaker incentive to purchase insurance than the tax penalty in the individual mandate of the type currently in the ACA (which has a certain short-term impact).

A cost-effective health insurance system requires that everyone be part of it. While it is unclear that legislation can legally force the purchase of services provided by the private sector, strong financial incentives should be provided to do so. I believe that Congress should determine a fair cap on the percentage of one’s income that should go to health care and require that an individual devote an amount up to that cap to health insurance and/or healthcare. This would take the form of a tax of up to that percentage if one does not purchase insurance. I have suggested 10%, but clearly that amount is debatable. If the individual can purchase health insurance for less than that cap they could save money by doing so. If that percentage is insufficient to cover the cost for actuarially fair insurance, people should be required to contribute that percentage with a subsidy to cover the difference. This structure would provide a strong incentive for an individual to purchase insurance while not imposing a financial burden on insurance companies for covering low-income individuals. In addition, if someone opts to not purchase insurance, the amount taxed should be available to that individual in the form of a health saving account. The percentage of that amount that could be rolled over is a worthwhile subject for debate.

- Eliminate the age-related limit on premium rate variation or increase the variation from the current 3 to 1 ratio to 5 to 1.

Rationale: Based on the data I’ve seen, the ratio of the actuarially fair cost differential of insuring someone in their 20s and someone in their late 50s or early 60s is roughly 5 to 1. Setting the ratio at 3 to 1 causes distortions that unfavorably impacts young adults and, as a result, degrades the risk pool. Insurance companies are reluctant to put themselves in a position in which they risk losing money with additional customers and will set prices for older adults so that they can recover their costs in that age group. The 3 to 1 ratio limits how much they can reduce premiums for young adults. The resulting premiums represent “unfair” insurance for young adults and discourages them from purchasing insurance. Discouraging young adults from purchasing insurance exacerbates the adverse selection problem in the insurance market and reduces the incentive for insurance companies to compete for older customers.

Raising the limit on age-related premium variation to 5 to 1 may have the effect of small increases in premiums for older adults but would allow substantially lower premiums for younger adults. The current system forces young adults to effectively subsidize the insurance of older adults. I believe this is undesirable for 2 reasons: 1) older adults generally have higher incomes and are better able to afford higher premiums ad 2) young adults should have a greater focus on saving for a home or retirement (or eliminating college debt) than older adults – higher premiums make that harder. If low-income older people cannot afford higher premiums, they should be eligible for subsidies.

- Allow people to buy in to Medicare or another government-supported public option. The premiums should be actuarially fair and cover the administrative costs so that providing such an option does not impose a cost on taxpayers (beyond any subsidies provided in point 2). A revenue tax should be placed on health care providers that do not accept payments from this option or other plans that offer insurance though individual exchanges.

Rationales: There are some markets in which competition is limited leading to a lack of insurance options. The lack of competition leads to higher premiums. Providing a “public option” that is required to charge actuarially fair premiums and break even ensures that there will be a fairly-priced option even in markets with few or no private insurers. The requirement that the option break even allows for fair competition from private insurers that would have an increased incentive to innovate and operate cost-effectively. The revenue tax would reduce the incentive of healthcare providers to opt for practices that are targeted toward wealthy patients and limit access to care through the public option.

- Set higher minimum standards for insurance by retaining (or possibly expanding) the set of fundamental benefits that are required to be covered and prohibiting high-deductible plans. High-deductible plans can be replaced by plans that offer substantial well-patient rebates in which insurers can offer rebates or future premium credits to individuals who do not require expensive medical care beyond standard health maintenance. The rebate could correspond to the amount of the deductible that isn’t utilized.

Rationales: The adverse selection problems that one sees in the insurance market as a whole also applies to insurance regarding individual conditions as well. For example, if policies are allowed that exclude treatment for mental health or addiction, then people who will seek those kinds of policies will be those who are likely to require those treatments. Insurance companies know this and will charge substantial price premiums for coverages that include those benefits, discouraging even more low-risk people from getting coverage that include them. Excluding conditions from fundamental benefits significantly diminishes the ability to get insurance for those conditions.

An argument for “skinny plans” that have high deductibles or copays is that some people will only want coverage for catastrophic events and that they should have that option. This allows insurance companies, with their superior knowledge of the probabilities and costs of procedures, to design policies that appear attractive but provide minimal actual coverage. Further, patients with a skinny plan that may greatly benefit from an expensive test or treatment may try to get by without it to avoid a large out-of-pocket expense, leading to poorer healthcare results. Furthermore, the presence of skinny plans creates an adverse selection problem in which insurance companies assume that people who want full insurance will be at relatively high risk and will raise premiums accordingly.

If only “high-quality” plans are allowed, a policy with substantial well-patient rebates would lead to very similar post-rebate financial outcomes for patients who remain healthy, but would greatly reduce the adverse selection problem and the inclination to skip potentially beneficial tests or treatments.

Suggestions for Lowering Healthcare Costs

1. Increase cost transparency by requiring healthcare providers to provide estimates of the cost of procedures before any non-emergency procedure is performed. These cost estimates should include 1) the price charged for the procedure by procedure code, 2) the expected total cost of the procedure (including the expected cost of drugs utilized, expected hospital stay, etc.), 3) the amount paid by insurance, and 4) the amount that will have to be paid by the patient. The cost estimates should also include likely contingencies (e.g. the price of other drugs that will be utilized, such as Tylenol). I suggest requiring Healthcare prohibiting providers from price discrimination on any basis other than financial need. Healthcare system/network membership could also serve as a basis for discounts or surcharges, but these should be published and readily accessible to patients and referring physicians. I also recommend providing a mechanism though which prices can be compared across providers making it relatively easy for the patient and referring physicians to compare the prices of different providers.

Rationales: Markets do not work if customers do not know the prices of the alternatives. In the vast majority of cases, patients have no idea of the price of procedures until after they are performed, if then. Furthermore, referring physicians often don’t know the prices charged by alternative providers. In one of my recent consulting projects we found that procedure price would be the second or third most important consideration in their referral recommendation (behind trust in competency and in some cases network membership), but over 2/3 of the referring physicians did not have more than the slightest knowledge of the prices charged by competing alternatives for basic procedures such as tonsillectomies or MRI scans. Anecdotally, I have found that many physicians don’t know the prices charged for the procedures they perform unless they are in private practice.

The lack of price information has led to a complete lack of pricing discipline and a large dispersion in prices, as is well-documented by Steven Brill in his book, America’s Bitter Pill. As an example, I recently had a CT scan and found after the procedure that the provider charged $10,400 for the procedure. After some research on my part, I found that the identical scan (by procedure code) would cost $800 at a local imaging center.

Better cost transparency would make it easier for patients to fully compare providers increasing price competition and imposing greater price discipline on the industry. This, in turn should lower overall healthcare costs.

2. The ability of pharmaceutical companies to charge exorbitant prices for proprietary drugs should be limited. There are several ways of doing this. I suggest limits to price discrimination on any basis other than financial need (which could apply at the country level). A relatively simple policy would be to require that the all US customers get most-favored nation pricing (perhaps, plus a reasonable percentage) among a set of developed countries, such as Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Japan. Such a policy would prohibit US drug prices from being more than a specific percentage above those charged in other developed countries, greatly reducing the price of proprietary drugs.

Rationales: The US prices for proprietary drugs often are 2-3 times as high as those paid in other developed countries, even after discounts negotiated by insurance companies. The rationale is that the price premiums are needed to ensure research and development, yet major drug manufacturers have dividend yields of 3.2% as compared with an average yield 2.28% for the healthcare sector as a whole (source: Dividend.com). From 2006 to 2015 the 18 drug companies in the Standard & Poor’s 500 index spent a combined $526 billion on buybacks and dividends” compared to their R&D spending of $465 billion (Source NY Times, Gretchen Morgenson). Price discrimination is a means by which drug companies increase profits at the expense of US patients and insurers and more of those benefits go to shareholders than go to R&D. If a lack of R&D funds becomes an issue, public-private partnerships might be employed.

Graphs showing the how certain Brand name drugs cost more in the U.S. than other industrialize nations.

3. Introduce tort reform to reduce the incidence of defensive medicine and the cost of malpractice insurance. These should include caps on non-economic damage awards.

Rationale: Excessive damage awards do little to encourage improved medical treatment since the awards are generally paid out of malpractice insurance. Further, they are generally awarded on a subjective basis by non-experts. Their primary effect is to raise the cost of malpractice insurance, which can provide a disincentive for talented individuals to get into medical practice, exacerbating a potential physician shortage. Researchers at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation concluded after reviewing 11 major studies that rates in states with extensive malpractice reform have gone up 6 percent per year as compared with 13 percent in non-tort-reform states.

In addition, physicians are more inclined to order marginally valuable tests and procedures to avoid the threat of a potential lawsuit. A 2012 study by Avraham, et. al. in The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization found that the most common set of tort reforms during this period reduces premiums of employer-sponsored self-insured health plans by 2.1%. A 2014 study led by the Cleveland Clinic and published in JAMA Internal Medicine cited a national cost estimate of $46 billion related to defensive medicine, but noted that those costs have only been measured indirectly. Other studies, along with the American Medical Association, put the cost impact much higher.

I suggest serious consideration to taking malpractice actions out of our legal system, where decisions are often rendered subjectively by non-experts, and establishing review boards comprised of healthcare and economics experts to review such cases.

I have other recommendations that are too complex to adequately cover here, including reforms to the fee-for-service reimbursement system and the incentives it provides for overuse. Hopefully these recommendations will contribute to a constructive discussion and will be taken seriously by our senators

About the Author

Scott Davis

Since 1997 Scott Davis has served as the Principal of Strategic Marketing Decisions, a consultancy he founded that specializes in marketing strategy, pricing and product design. Before founding SMD he served on the marketing faculties of the Olin School of Business at Washington University in Saint Louis and the Graduate School of Management at University of California, Davis. Since then he has taught MBA pricing and economics classes at a number of the country’s leading business schools, including the Haas School of Management at the University of California Berkeley, the Anderson School of Management at UCLA, the Carlson School of Management at the University of Minnesota and the Graduate School of Business at Stanford University.

He has consulted internationally on pricing and marketing issues in a variety of industries including healthcare, telecommunications, and packaged goods. His clients have ranged in size from new business start-ups to Fortune 500 companies.