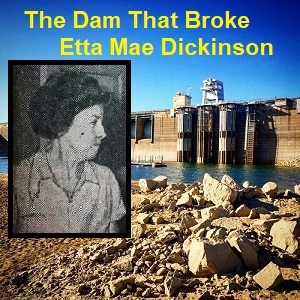

When the Folsom Dam project was finally authorized by congress in 1948 the residents in the footprint of the proposed Folsom reservoir knew that eventually they would have to leave their farms, ranches, and homes forever. The uncertainty and anxiety of having to move was too much for one woman. In 1952 Etta Mae Dickinson killed her father at their ranch home on the North Fork of the American River. After setting the home on fire, she was caught and transported to Auburn where she committed suicide at the Placer County Hospital.

Folsom Dam Construction Triggers Murder, Then Suicide

It was a typical spring morning along the American River fives mile north of the town of Folsom in 1952. 100 years since the big gold rush that had miners swarming across the banks of the north and south forks of the American River, this part of rural Place County had settled into a quiet bucolic community. One family that called the area home was that of James Peter Dickinson, his wife Katie Mae and their daughter Etta Mae. Mr. Dickinson liked to go by his middle name Peter.

At 78 years old, Peter had lived through two world wars and the Great Depression on his ranch on the river. But in 1952 he and his daughter Etta Mae were facing the condemnation of their property so that Folsom Dam could flood the property with water to create Folsom Lake. Peter Dickinson purchased his ranch land in this historic gold rush region in 1918. Peter and his wife Katie Mae took out a mortgage of $2,000 to purchase the 210 acres that ran all the way down to the river. They completely repaid their mortgage to Wells Fargo Bank and the Roman Catholic Bishop of The Diocese of Sacramento in 1927.

Rock Spring House On The Dickinson Ranch Land

It was a nice piece of property situated for growth. On the northwest portion of the property the North Fork Ditch cut through the land. This water canal constructed in the 1850s to provide water to the gold mines was now supplying water to farms and ranches like the Dickinson’s. There was also Rock Spring on the property that gurgled out water year round to keep the grass green. Rock Spring literally put the property on the map. Before North Fork Ditch was built, Rock Spring was a place where the early pioneers would stop to get a drink of water. The Rock Spring House was listed on an 1866 Government Land Office map.

There was also the North Fork of the American River on the southeast section of the Dickinson property. A man could go down to the river and fish for salmon or shoot a goose for supper. The Dickinson property had the main road from Folsom to Auburn running through it. This paved county road made it easy to get cattle to market. In addition to these amenities, the property was surrounded by beautiful oak trees and granite outcroppings, some of which that had Native American grinding holes embedded in them. In short, the area was rich in history and resources for any family to have a comfortable life and earn a living.

Etta Mae Grew Up In The Granite Bay Area

Peter’s daughter, Etta Mae, was 15 years old when he bought the property that included the Rock Spring house. Peter’s wife, Katie Mae, had emigrated from Ireland in 1902 at the age of twenty. By 1903 Peter and Katie Mae were married and had little Etta Mae. The family was not alone as Katie Mae had numerous relatives in the Folsom and Sacramento region.

In 1947 the Dickinson family suffered a great loss as Katie Mae died of heart failure. Peter was 73 years old at the time of his wife’s death. That meant that Etta Mae, still living at home, would be the sole care taker for her aging father. More change was to come as the Folsom Dam project was approved in 1948. Shortly thereafter, the Dickinson’s would be getting daily reminders that life was changing as more cars, trucks, and earth movers passed through their property heading north to build the dykes in today’s Granite Bay area for Folsom Lake. Off in the distance, they could hear the explosions of dynamite as the dam builders blasted the large monoliths of granite that formed the American River’s banks for Folsom Dam. The quiet Dickinson ranch land was no longer as bucolic as it once was in 1918.

Dickinson Ranch To Be Flooded By Folsom Lake

Eventually, the Army Corp of Engineers contacted Peter Dickinson about selling his land. Most of the land that Peter owned would be below high water mark of 466 feet of elevation of a full Folsom reservoir once Folsom Dam was built and the lake filled. The other portions of Dickinson Ranch land above 466 feet of elevation were also being acquired by the Army Corp in order to have access to all points around the reservoir. There was no escaping to higher ground on property he already owned. He and Etta Mae would have to move. By all accounts, the prospect of moving was most stressful to Etta Mae.

Etta Mae Returns The Government Check

The Dickinson’s agreed to a purchase price of $25,000 from the Army Corp of Engineers for the property. Once the settlement check arrived, dread and indecision overcame Etta Mae and she returned the check to the government. Then the family received information that the government would be condemning the property which meant they may actually get a smaller reimbursement amount than the $25,000. Etta Mae began to quarrel with her father over their future. She argued with the Army Corp of Engineers. Neighbors reported that Etta Mae was acting more erratic in the spring of 1952.

On April 10th, the Auburn Journal published an artist’s rendering of what the Folsom Dam would look like with the reservoir waters behind the dam. It was a subtle reminder that most of the region was looking forward to the big dam and lake to follow. There was no organized protest against the Folsom Dam project. There was no one advocating for the families who were being displaced. The government had now become the over powering adversary to little farms, dairies and ranches in the way of an all-important flood control project for Sacramento.

The weather forecast for Thursday April 11 called for breezy conditions with wind gusts up to 20 miles per hour. The temperatures would be cool with lows in the 50s and highs in the upper 60s. Overall It was to be a wonderful April spring day along the American River. A bonus for folks who wanted to be out in the evening would be the rising of a full moon over the river canyon and hills. It was on this morning, with wild flowers bursting forth on the hillsides, a spring day most suited for life, leisure, and work that Etta Mae decided the end had come for both her father and herself.

The Last Breakfast

As her 78 year old father ate the breakfast she had prepared for him, she picked up the family shotgun, pointed it at the back of his head, and pulled the trigger. She then poured kerosene in the living room, kitchen, and on some of her clothes tossed on the floor, and set the house ablaze. She later recalled she had every intention of dying in the fire along with her father. Death was the only way out of the dilemma she had created as she saw it.

The flames and smoke were intense. Etta Mae couldn’t bring herself to step back inside the inferno she had just sparked. At 48 years old, she saw her whole life going up in flames. She retreated to the barn, let out the animals, and contemplated killing herself. She tried to commit suicide with the shotgun but found it too difficult to get it in place and pull the trigger. Or, maybe, she just wasn’t ready to die. With just the clothes on her back and the shotgun in her hand, she wandered off among the oaks, buckeyes, manzanita, and gray pines that populated the hills on their property.

From a distance she watched as the neighbors and fire crew came to extinguish the house fire. The expectation from those rushing to the scene was that they would find two bodies; that of Peter and Etta Mae. Only one body was found in the ashes. Late in the afternoon, after the remains of Peter Dickinson had been removed, Etta Mae was spotted looking down upon the scene from a vantage point up the hill behind some trees and shrubs.

Realizing that she had been seen, Etta Mae hid the shotgun behind an old log nearby as Placer County Sheriff Charles Ward approached her. She walked down to the road but was hesitant. One of the neighbors, Joseph Mooney, whose family had homesteaded 160 acres (NE1/4, Section 12, T10N, R7E, 1883) on top of a ridge overlooking the river and would later be known as Mooney Ridge, came down to reassure Etta Mae it was fine to talk to the Sheriff. After some initial false statements about the house fire, she finally admitted that she had shot her father and set fire to the house.

It was apparent to the Sheriff from the comments of the neighbors regarding Etta Mae’s behavior and her inconsistent statement about how the fire started, along with her actions, that she may not be entirely mentally competent. He transported her up to the DeWitt State Hospital in Auburn for a mental evaluation. DeWitt State hospital was formerly the DeWitt General Hospital built by the U.S. War Department to treat wounded service members. In 1947 the facility, which was comprised of many long, narrow, barracks-like buildings, was conveyed to the State of California.

The primary focus of the DeWitt Hospital was on psychiatric disorders and illnesses. Etta Mae was evaluated by doctors at DeWitt and admitted into the hospital as an emergency patient Friday, April 12. At the same time, the Placer County Sherriff was arranging for a murder warrant against her for killing her father. On Saturday she was charged with murder and transferred to the Placer County Hospital where she was put under observation. Neither the DeWitt Center buildings nor the Placer County Hospital where Etta Mae was detained are still standing.

Etta Mae was becoming increasingly agitated at her state of affairs. She began to hit herself on the head with her shoes at the DeWitt Hospital. Upon being transferred to the county hospital her shoes were taken from her, but she was allowed to keep her stockings. Deputy Matron Millie Roth, who was in charge of monitoring Etta Mae, testified that when she checked on her she was wearing only a hospital gown. Previously, Etta Mae had been observed walking around her room with the stockings draped over her shoulder. But when Matron Roth checked on her on Saturday afternoon the stockings were nowhere in sight.

The Suicide Of Etta Mae Dickinson

Speculation by Matron Roth was that Etta Mae had hid her stockings in a book that she was allowed to have in her room. Matron Roth went to supper at 4:30 pm. The last known observation of Etta Mae was of her gazing out of the window of her room. At 4:50 pm when Matron Roth returned, she found Etta Mae on the floor between her cot and the window with the stockings tightly wrapped and knotted around her neck. The nurses cut the stockings off and administered respiration efforts, to no avail. Dr. Everette Dick pronounced her dead at 5:05 pm that evening.

There is little record of Etta Mae Dickinson’s mental health. We do know that she quarreled with her father about making a last will and testament. Unbeknownst to her, Peter Dickinson did make a will bequeathing the property to her. The question arises as to why he would hesitate leaving the property to Etta Mae unless he had doubts about her mental capacity to run the ranch or any subsequent estate. In the fog of mental duress, this might have played a role in the logic of Etta Mae to commit suicide as she, from her perspective, was utterly destitute and without a home.

Since Etta Mae survived her father, she inherited the property. But now Etta Mae herself had died. There were two applications to administer the estate of Etta Mae Dickinson, one from the County Coroner Francis E. West to become the public administrator and another from Mrs. Mabel A. Brown of Folsom who was a cousin to Etta Mae. Mabel Brown ultimately prevailed because on June 6, 1952, she filed a public notice to all potential creditors to file claims for payment from the estate of Etta Mae Dickinson. Mabel Brown was listed as the administratrix of estate in the legal notice. The deed records I have found indicate the ranch was mortgage free.

One item that was odd to me, but perhaps not to someone more knowledgeable in these matters, was that the Roman Catholic Bishop of the Diocese of Sacramento was listed as a creditor on the mortgage documents. I don’t know if the diocese actually lent the Dickinson’s money, along with the bank, to purchase the property or if they were merely a cosigner to the loan. Additionally, I don’t know if the participation in such mortgages by the Roman Catholic Church was commonplace in the region. If I acquire more information about this I will edit this post to include what I have learned.

The various newspaper accounts all refer to the Peter Dickinson ranch as being 326 acres. I can only account for 240 acres from deeds on file with Placer County. In the 1956 book “The Story of Folsom Dam” by Joe Blenkle, a souvenir book printed for the completion of the dam, he notes that Peter owned 400 acres and had rented land in the area before buying his property. Blenkle mentions that Dickinson was interviewed in 1950, apparently in connection with the Folsom Dam project and the impending loss of his land, and wrote that Peter was a cattleman who still enjoyed riding through the hills at the age of 76. In addition, Blenkle reported that the Dickinson home was the “Old Rock Spring Ranch” or also known as “the Old Prisser place.”

I have yet to stumble across any Prisser family connected to the land in question. But the Rock Spring House is indicated on several maps. The name was given to the house because of its proximity to Rock Spring less than a ¼ mile to the north. There is no doubt that the Rock Spring House was on land owned by Peter Dickinson. The question remains as to whether this was the Dickinson residence where Etta Mae shot her father Peter?

In the drought of 2014 – 2015 Folsom Lake water levels dropped to historically low levels. Most of the old Dickinson ranch land was dry for the first time since the 1977 drought. I’m relatively certain that the remains of the house shown below are the Rock Spring House based on maps of the area. It could also be where Peter Dickinson met his fate and Etta Mae started slipping toward her inevitable suicide in Auburn.

There are unconfirmed reports that Mabel Brown donated part of the land to the California State Parks to be used as the entrance for the Granite Bay Park at Folsom Lake. What is confirmed, is that Etta Mae, her mother Katie Mae, and her father Peter are all resting together at East Lawn Cemetery in Sacramento.

Podcast

A sincere note of appreciation to Bryanna M. Ryan, curator of the Placer County Archive in Auburn at the DeWitt Center, in assisting me with gathering information for this history post.

Images of Dickinson deeds and newspaper clippings from the Placer Herald and Auburn Journal reporting on the tragic events of the Dickinson murder-suicide incident.