A day hike in the Sierra Buttes with my son was great until I got lost. At 57 years old, I had no problem with the 10-mile hike and 2,300 gain of elevation. I was shocked that I was hit with acrophobia climbing the stairs to the Sierra Butte’s Look Out station, and then getting lost hiking back to the car. Fear and dread welled up inside of me.

The Covid-19 pandemic and ensuing lock down cemented my slow acceptance that I am no longer young, handsome, smart, destine for fame and fortune with a future that is unlimited and full of hope and happiness. In short, I’m an old man. I have acquiesced to the fact that my highest achievement in life is now to be content with what I have and what I can do.

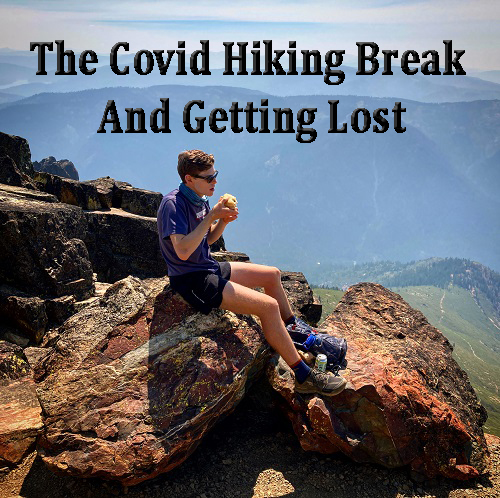

Hiking To The Top Of The Sierra Buttes

His world revolves around organic chemistry and pharmaceuticals at MIT. My world focuses on California history when distilled spirits were considered medicinal. The one intersection between the generations is hiking. On this day, September 4, 2020, the hike was to the 8,587-foot location of the defunct fire spotting surveillance perch in the Sierra Buttes.

The last couple miles up to the top of the Sierra Buttes is physically challenging as the slope, on average, is steep. When I made it to the base of stairs, I felt good. Then I started to walk up the stairs, which span the deep chasms between the mountain rock and I froze. I was gripped with acrophobia, fear of heights.

I knew the genesis of this sudden onset of acrophobia. The previous year I had problems with my shoulders and gripping items. They still are not 100 percent, even though the mysterious affliction seems to have passed. Possibly related, I’m not lifting my right leg as high as I should when I walk. This leads to stupid stumbles as my hiking shoes catches a rock, like it did many times hiking up the trail. A quick review of my maladies and it was apparent that I would trip on a stair step, not be able to hold my balance, and fall into the chasm below me.

I gripped the side rails as tight as I could and deliberately put one foot in front of the other as I climbed the stairs. I did not look down. My focus was on each stair step. I counted them to distract myself. Upon setting my feet on the hard rock path at the top, I was relieved, if not unnerved, at this new emotional fear I just experienced.

Getting Lost In The Sierra Buttes

Return hikes are pretty easy, especially when it is all downhill. We had made a few turns and transferred to other trails, but I thought there were plenty of landmarks to keep me on track. I wasn’t paying attention too closely as the leader our hike, my invincible 23-year-old son, knew what he was doing. He had hiked around this region the year before while traversing a portion of the Pacific Crest Trail. We had escaped Covid-19, but not the omnipresent smoke from thousands of acres of California forests burning. The hike was so physically distanced – with the young man virtually racing down the hill – that this old man got lost.

After I had passed all of the high Sierra mountain lakes, the trail and landscape all looked the same and not familiar. Where was I? Which way back to the car? Do I sit in one place? Do I retrace my steps to the last familiar spot? Did I make a wrong turn or several wrong turns? Where in the hell was my kid? It was a mixture of dread and mild panic.

My fear was no longer from the pall of smoke engulfing the mountains and valleys or catching Covid-19 and dying alone in a hospital bed; I was now gripped with the fear of spending the night alone in the wilderness. I wandered over various trails and roads blowing the recue howler whistle with a certainty that no one would hear my futile attempt to summon assistance.

Where was the young man, whose diapers I changed when he was a baby, and why wasn’t he looking for me? Never has such panic and a sense of my own mortality gripped my little brain. There was only a couple of ounces of water left in my bottle, no food, and I packed only a light long sleeved shirt. I hopefully surmised that it was going to be a long night before rescue.

For months, I had been so vigilant at protecting myself from a virus I could not see, only to become lost in a terrain that I could see and touch. My savior was in the form of a little tag labeled PCT. I figured if I stayed on the Pacific Crest Trail I would eventually come to a road or camping spot. I followed the PCT for the next 90 minutes over a trail that did not look familiar. I ventured down an old dirt road to see a gate I remembered walking around six hours earlier. Finally, something looked familiar.

As the parent of an adult, you must resist the urge to scold or argue with your child. It is a matter of respect, like you would display with any friend or stranger. This was a point, a moment in time he would not be aware of, where I, his father, swallowed my parental superiority and engaged him as an equal. He calmly sat in the car awaiting my return. “It did not occur to you that after 90 minutes your father might be in distress?” “No,” he said, “You always hike slower than me.”

I saw little use in trying to convey my fear and panic, if it was only for a brief period of time. Instead, I focused on my safe return and that my son was also safe. I knew that at the age of 23, he could not completely comprehend the wave of fear and uncertainty that can envelope an older person, whether the genesis of the foreboding is from Covid-19 or being lost in the forest. His perception of my anxiety over being lost was that it was irrational, illogical.

My son, fortunately, does not hold the same perception that the fear of catching Covid-19 is irrational, albeit that it is a little over hyped. He is appropriately respectful to wear a mask always indoors and keep a safe distance. I must assume, that when he is my age, and the body doesn’t function like it did 40 years earlier, and you know your physical limits, that he will not find the fear of being lost in the woods is irrational, but a part of life.