Unlike the destruction of gold mining along the American River at Folsom Lake, Native Americans changed the landscape very little even though they lived in the area for thousands of years.

I slipped my shoes off and stepped on to the massive granite boulder along the North Fork the American River. My feet felt the slight sting of heat from the granitic monolith that was normally under the waters of Folsom Lake, but had been baking in the hot summer sun. An old man with gray hair, I now owned this rock that I was certain had not been touched since the days of the gold rush. As I surveyed my imperial perched overlooking the rushing waters of the river below, I noticed holes in my rock. “What man hath scarred my throne?”, I wondered.

Native Americans Before The Gold Rush

From the perspective of most people in the Sacramento region who visit Folsom Lake, there was no life before the dam. In 1977, I was a 12 year old running up and down Granite Bay Beach in the Junior Life Guard program. Folsom was a giant swimming hole surrounded by picnic tables. Sometime during my elementary school education I learned about the gold rush, the ‘49ers, and the manifest destiny of Americans to exploit whatever natural resource they could get their hands on.

Oh yeah, there were Indians someplace in California. But those people lived someplace else, certainly not in my back yard. Indians lived in museums. They put their woven baskets up on walls and the arrowheads under glass. Indians lived in a few places where the Parks department had built little brush display huts under oak trees. The lasting impression of a young child growing up in the 1960s was that there were a few Indian villages scattered along the rivers in Sacramento. The real story was the gold rush, Old Sacramento, bar fights, and bordellos. Our real history started with the mass migration of men from the east in search of gold. Indians: colorful bit actors in a larger drama of empires and the transcontinental railroad.

A Few Clues To Native American Life Before Folsom Lake

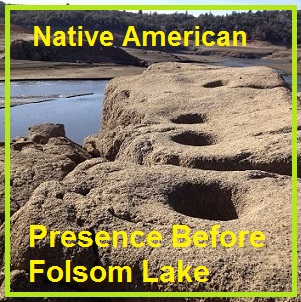

Numerous Native American grinding holes dot the landscape along the North Fork of the American River where granitic formations were favorable to creating a mortar in which to grind acorns.

Every year when Folsom Lake water levels drop, I go hiking around the lake bed searching for history. The years when the lake dropped really low because of the drought was a bonanza of hiking and historical finds. The first Native American grinding holes I came across were a real novelty for me. “Wow”, I thought, “Someone was here before me, the lake, and the gold miners.” I came across more and more of the grinding holes along the North Fork of the American River. Then it occurred to me that there just weren’t a few Native Americans here before us, but a whole community.

If you search through books or online you’ll come across all sorts of references and history about the historical mining activity along the north and south Forks of the American River. There were old towns like Salmon Falls and Rattlesnake Bar, and colorfully named mining areas such as Condemned Bar. But where were the sites of the Native American villages? There just aren’t a lot of references to prehistoric sites. But it is undeniable that early prospectors and miners encountered Native Americans in their travels along the North and South Forks of the American River.

1977 Surveys Of Prehistoric Activity At Folsom Lake

While there were a few archeological surveys done prior filling of Folsom Lake, the bulk of the sites along the north and south forks of the American River were recorded in 1977. The California State Parks Department took advantage of the extremely low water levels of Folsom Lake during the drought of 1977 to survey the area for prehistoric Native American activity. The Parks Department has also documented other sites as new roads or recreational facilities were proposed within the Folsom Lake State Recreation Area and cultural resource surveys were triggered.

Over fifty Native American sites along the north and south forks of the river within the Folsom State Park boundary have been formally identified and recorded. Some of the sites represented camps or perhaps small villages while others were work centers or quarries where evidence of tool and projectile manufacturing might have occurred. A few sites represented burial grounds or ceremonial sites.

The Parks Department essentially swept up most of the Native American artifacts that they found. Their preservation operations along with people who took home the found arrow head, have effectively removed most remnants of Native American occupation around Folsom Lake. However, some people will come across Native American grinding holes on top of granite boulders or outcroppings as they roam around the lake.

Black Oak acorns were ground into a fine powder and used through out the year to create a much or cakes.

While the grinding holes can be found throughout the area, they are mainly concentrated along the North Fork of the American River where the granite outcroppings are most abundant. The river canyon of the South Fork of the American River is mainly composed of metamorphic or slate rock and does not lend itself being drilled for the purpose of creating a mortar in which to grind acorns. Portable mortars for grinding acorns were found along the south fork where Native American sites were recorded.

A report on the California Parks Department large cultural resource survey from the late 1970s concluded that the sites recorded corresponded to previous research on Native American villages and camps. Specifically, most of the sites tended to be on knolls with moderated slopes bounded by drainage or creeks on either side. The sites had southern exposure and were near grinding holes. Other artifacts such as projectile points, rock knives, beads and ornamental shells were also recorded. The only remnants of the actual shelters were the outlines of depressions created when the hut was built.

I’m not an anthropologist or an archeologist. But if you were going to set up a permanent or seasonal camp, where would you put it? You are not going to set up camp where you are going to be washed away in a flash flood from a creek. Having a camp with southern exposure will give you the most light and warmth. The Native Americans lived off the land. While there was trade between different Native Americans from the coast, valley, and in the mountains, most of their food sources occurred locally. In the fall they gathered acorns to grind up for mush or cakes. They hunted deer and other small mammals. Geese and other birds were also hunted. They fished for salmon and eels in the river. Native Americans had a whole way of life with their own creation mythology and ceremonies to mark seasons, births, and deaths.

Native American Way Of Life

Before being used to weave baskets, branches or pine needles were soaked in water to make them pliable.

I often hear people discuss how they don’t want to lose their way of life. The farmer doesn’t want to lose their way of life to a housing development or freeway. Ranchers don’t want land policies that might restrict their grazing rights because it threatens their way of life. Fishermen dread the closing of parts of the ocean to fishing because they could lose their livelihood. These folks engage in a distinct and unique vocation that necessitates a particular way of life. It’s in their blood. The lifestyle has been in their family for generations. It’s who they are. They farm, ranch, fish, mine, hunt, work hard, and enjoy the fruits of their labor. We are very good at creating myths and identities around a way of life. There is nothing wrong with attaching significance and identity to an occupation.

The Native Americans who occupied the land along the North and South Forks of the American Rivers were all of the above: farmers, ranchers, miners, fishers, food processors, hunters, gathers, and home builders. They had a way of life that was every bit as valuable as the immigrants who claimed ownership to the lands along the river beginning in 1849.

Native Americans appear to have had an interconnected and dependent – and somewhat fragile – economy of subsistence. They were not generating excess amounts of food stuffs or creating goods that put them at an economic trading advantage with other regional Indians. There were seasons for hunting when the deer came down from the hills during mating season. Fishing during the Salmon runs. Hunting ducks and geese during the winter. Harvesting acorns during the fall. Collecting berries during the spring. They were the ultimate survivalists.

Pine needles could be tightly woven into baskets used for food gathering and preparation by the Native Americans.

Hundreds of Native Americans called the land under and around Folsom Lake home before the gold rush. As the miners came in and disrupted and destroyed a fragile subsistence from the land, confrontations were bound to happen. Newspapers of the time are filled with accounts of atrocities on both sides. There is also mention of Native Americans taking an active role in mining activities. But overall, the mood of the immigrants was that they could not coexist with the Native Americans. Something had to give, and it was the Native American way of life.

While the Native Americans were derisively portrayed as savages in many historical accounts, they were obviously better suited, prepared, and thrived in a land without modern conveniences. In his 1852 book “California Illustrated: Including A Description Of The Panama and Nicaragua Routes”, author J. M. Letts recounts his time mining and selling goods on the North Fork of the American River near Lacy’s Bar. In chapter 20 he details how difficult life on the river can be for an ill-prepared immigrant.

Flash Floods

General Winchester and company had just placed their quicksilver machine, and commenced successful operations on the bar, but one night destroyed their works, carrying one of their machines, laden with twenty-five pounds of quicksilver, a distance of three miles, destroying it, and emptying its valuable contents into the river. The rise of the river was so rapid that those on the opposite side, when it commenced to rain, found it impossible to re-cross six hours after. The scene was most terrific; the mountain on either side of the river, rose almost perpendicularly, and the torrents rushed down, undermining huge rocks, which, after making a few leaps, would come in contact with others of equal dimensions, when both, with one terrific bound, would dash into the chasm below.

Lack of Proper Shelter

The store I occupied was made by driving stakes into the ground, and inclosing with common unbleached muslin; the roof flat, covered with the same material. It had answered a good purpose during the summer, but for the rainy season, I am not prepared to say it was exactly the thing. I do not know that the rain fell faster inside than out, but some of my neighbors insinuated that it did. I could keep tolerably dry by wearing an India rubber cap, poncho, and long boots, with the aid of a good umbrella; in short, this was my regular business suit. For a bed, I had a scaffold made of poles, on which I had a hammock stuffed with grass and straw, using a pair of blankets as covering. In order to keep my bed dry I had a standard at the head and foot, on which was a pole running “fore and aft,” serving as a ridge-pole, over which was thrown an India rubber blanket. On going to bed I would throw up one corner of my India rubber blanket, holding my umbrella over the opening, and after taking off my boots, I would crawl in feet first, throw back the rubber to its place, then tying my umbrella to the head standard I was in bed. My friends, Fairchild, Tracy, Jones, and Dean were not so fortunate. They would lay down on the ground in their blankets, and in one hour would be drenched to the skin; in this condition they were obliged to spend the balance of the night. Jones (formerly of the Cornucopia, New York) had a severe cough, his lungs being much affected, and he thought he was fast declining with the consumption. After becoming drenched and chilled his cough would set in, which, together with his distressing groans, would render night hideous, and cast a gloom over the most buoyant spirit.

Land Scurvy

A disease at this time manifested itself, the symptoms of which were of a peculiar nature. It was called the “land scurvy,” and was caused by a want of proper vegetable diet. The blood of the system became thick and turgid, and diminished in quantity; there was but little circulation at the extremities, or near the surface of the body, the fleshy parts becoming almost lifeless; the gums became black and not unfrequently the teeth would fall out, the gums having so entirely wasted away. The malady became fearfully prevalent, and no remedy could be obtained; vegetables were not to had, there were none in the country. There had been a few, a very few, potatoes in the market, at prices varying from four shillings each to a dollar and a half per pound, but the supply was too scanty to arrest the disease, and many had become almost entirely disabled.

On the 28th of October, a man from Illinois fell a victim to this dreadful malady, and on the 29th, it was our painful duty to bear him to that lonely hill and consign him to the tomb. A board was placed at his head, on which was cut his brief epitaph. What a strange commentary upon the vicissitudes of human life. He was once an infant, fondled and caressed by an affectionate mother, a youth counseled by a doting father, and embraced and loved by sisters and brothers.

Surviving On The American River

The Native Americans were accustom to, and prepared for, the environmental elements of the low foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountain range. They placed their camps away from rivers that could rage with floods without warning. They knew how to build shelters that protected them from wind, rain, and cold temperatures. Their varied diet of meat, nuts, grains, and root vegetables kept their bodies healthy. Yet, it were the Native Americans who were uneducated and inferior to the immigrants who suffered so profoundly at the hands of the hubris of their own abilities.

Failed Treaties

There were clumsy attempts at creating treaties and setting aside land for reservations. But there was a lack of political will to ratify the treaties. Attempts to change the substance of the treaties to accommodate mining interests undermined the confidence of the Native Americans about any real recognition. The lack of progress on the treaties and the threat of changing the terms were not lost on everyone. This editorial from 1851 in the Sacramento Daily Union summarizes the disgust some people had for the way Native Americans were being treated.

Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 1, Number 134, 22 August 1851

“Rank Injustice.

We are sorry to perceive an attempt to make political capital out of an exceedingly serious and important correspondence which has just taken place between Brevt. Brig, Gen. E. A. Hitchcock and Governor McDougal. We regret it because it evolves principles of injustice so monstrous that a man of moral reflection, or a man who understood the principles upon which our political institutions are founded, could not, it seems to us, express sentiments so insensible to the natural, just and cherished rights of the original owners of California.

The idea that nothing is due to the Indian tribes of the State, but that kind of Christian forbearance which would exterminate them without an effort by even the shadowing of justice to conciliate and improve them — the idea that the convenience of the white man, tutored in all the advantages that belong to civilization, is to be propitiated by forcing these people from their valley homes and the treasured ashes of their dead into the barren and inhospitable haunts of perpetual winter, may answer the purpose of those who hold that the ascendency of a party ticket is paramount to the laws of God and humanity.

But if the Whig party, to the advancement of those interests we have appropriated the columns of the Union, expect of us to make use of such capital, we will at once repudiate a position so unhallowed in moral associations, and so repugnant to the dictates of nature, and the promptings of an enlightened age.

The history of our State, proves, that a large proportion of the Indians of our country are docile, easily governed and susceptible of a tolerable degree of civilization — proves that a few men have settled among these Indians, occupied their lands, and availed themselves of their labor without incurring the least personal injury, by simply supplying towards them that sort of kindness which could be manifested by a few blankets and beads.

It is also a matter as susceptible of proof, that since the gold discovery upon their ground, they have been extensively employed in digging the ore, and the results of their labor have gone to enrich those men who had the most of the worthless trinkets that were falsely estimated by them.

And now. when almost every valley and stream of the State has been taken from them, and a sense of their loss is beginning to be felt in their ranks, now when, by an authorized treaty of Government, they are having taken from them which an honorable treaty vouchsafes, it is totally unbecoming and unwarrantable to treat them with such indifference, or to make such a use of a negotiation that was not necessary, but one probably which, contemplates he great bulk of advantage upon the side of might and intelligence.

It has been the opinion of those men who have been employed in the Indian difficulties of different sections of the country, that treaties respecting and preserving their rights would make them our friends instead of foes. And now when an effort is made to try this experiment, under great disadvantages we admit, to see a public print recommending, not a careful investigation of the justice or necessity of such a treaty as has been made, but recommending in terms that cannot be misunderstood, a violation of the contract, which has been honestly and fairly effected.”

Native Americans Disappear

There is no record of when the last Native American camp ceased to exist in the Folsom Lake region. Many historians note that by 1853, most of the Native American population had dispersed, move south, died in conflicts with immigrant settlers, or died of disease. But there is no doubt that there was a thriving Native American population and culture along the north and south forks of the American River. Where Native Americans once ground acorns, skinned deer, or fashioned tools from local rocks, Folsom Lake visitors now fish, hike, ride horses, bikes, and have picnics.

Some roots, such as the soap root, are very fibrous and could be fashioned into brushes once properly prepared and dried.

While the Parks Department does their best to educate people about not disturbing Native American sites or lifting artifacts they may find, they could do more. The visits to Folsom Lake are increasing and in particular mountain bike riding. Many trails have become severely eroded with the number of bikers using the trails all year round even during winter when the soil is wet and most susceptible to erosion.

If we are to have respect for the ancestral homeland of thousands of Native Americans who called Folsom Lake region home, if we value the sacredness of this land by people who were pushed from it, and if we embrace the concept that public parks are a resource for all people to enjoy, then the Parks Department has an obligation restrain the degradation of the land.

The documented sites of Native American activity in and around Folsom Lake are a carefully guarded secret. The fear is that if the sites become known, people will attempt to hunt for artifacts. It is virtually impossible to see any of the artifacts collected by the Parks Department out at Folsom Lake. I’m sure, if they could have, they would have removed the grinding holes drilled into the granite.

Thin rope was made from the fibers of certain bushes. The rope was used for netting fish and catching birds along the American River.

I’m not saying that the wisdom of the Parks Department and trained archeologist is wrong. I’m just pointing out the result of their preservation efforts have left the Park vacant of any educational signs or outreach that Native Americans used the area long before suburbia invaded. It is not uncommon to see cars and trucks roaming over the beaches of Folsom Lake that were once Native American camps. Mountain bikes are allowed to careen down trails exacerbating erosion on the hillsides. Where are the anthropologists and archeologists to inform Park visitors of the history? Or are they only concerned about their work and the artifacts they find?

When I hike, I still scramble up granite boulders to see what I can see. Now I see more. I just don’t look for the history of the gold rush or the remnants of old water canals. Now I realize my foot was not the first to be placed on that granite. The sights, sounds, and smells around Folsom Lake and up the river canyons are similar to what the Native Americans experienced long before the immigrants came in search for the gold dust in the river. Babies were born on the river. Old men, like me, died on the river. Mostly I hear nothing. It is quiet for the most part. Everyone is gone.

Author’s note: research for this piece was based on numerous cultural resource reports located at the California Department of Parks Archives, several books relating to Native American history in Northern California, review of 19th century newspaper stories related to Indians in California, and discussions with archeologists and anthropologists. The images of Native American grinding holes are from my many hikes in the region. The photographs of traditional handmade Indian goods were on display at a local gathering of Native Americans on the Bear River.

September 11, 2017 Addition

I have come across few firsthand accounts of Native Americans during the gold rush in the Folsom Lake region that provided objective information about their lifestyle free from negative stereotypes being attributed to the people. This account of an encounter with a tribe of Native Americans is from Edward Gould Buffum’s book “Six Months in the Gold Mines”. While the encounter occurs closer to the Yuba River, it at least gives a glimpse of life of Native Americans residing in the foothills just east of the Sacramento Valley.

Chapter 2 November 1848

Expedition party has traveled from Sutter’s Fort northeast to find Johnson’s Ranch on the Bear River. After a couple days travel, and drying out after a couple of rain storms, they come to what Buffum calls Beautiful Camp. They had walked up a dry arroyo, the ground over which was “miserable stony soil” as he puts it. He describes meeting the foothills and seeing numerous little valleys surrounded by tall hills. After hiking for about a mile, they settled on a circular valley, one mile in diameter, surrounded on all sides by hills except for a narrow entrance into the valley. Page 29

I estimate they were somewhere between Rocklin and Lincoln, possibly in the Clover Valley area. This area has/had dry washes and tall foothills fan out on to the valley floor. They may have walked up the mouth of Auburn Ravine.

After spending the night, Buffum goes exploring in the morning and comes across what he believes to be an Indian grave. He found Native American grinding holes on the large rock under which they had camped the night before. There was plenty of white oak (Quercus longiglanda) in the area to provide acorns.

Page 30

…I took a stroll across the little stream, with my rifle for my companion, while the others, more enthusiastic, stared in search of gold. I cross the plan and found, at the foot of the hill on the other side, a deserted Indian hut, built of bushes and mud. The fire was still burning on the mud hearth, a few gourds filled with water were lying at the entrance, and an ugly dog was growling near it. Within a few feet of the hut was a little circular mound enclosed with a brush paling. It was an Indians grave, and placed in its centre, as a tombstone, was a long stick stained with red colouring, which also covered the surface of the mound. Some proud chieftain probably rested here, and as the hut bore evident marks of having been very recently deserted, his descendants had without doubt left his bones to moulder there alone, and fled at the sight of the white man.

Page 32

After two days hiking they finally reached close to Johnson’s Rancho on the Bear River. They gathered some provisions from Johnson and headed up three miles to the Yuba River mines. As he and Higgins, one of his traveling companions, were out hunting, they came across some Native American women gathering acorns.

Page 33

We made our way into the hill, and were travelling slowly, trailing our rifles, when we stopped suddenly, dumbfounded, before two of the most curious and uncouth-looking objects that ever crossed my sight. They were to Indian women, engaged in gathering acorns. They were entirely naked, with the exception of a coyote skin extending from the waists to the knees. There heads were shaved, and the tops of them covered with a black tarry paint, and a huge pair of military whiskers were daubed on their cheeks with the same article. They had with them two conical-shaped wicker baskets, in which they were placing the acorns, which were scattered ankle deep around them. Higgins, with more gallantry then myself, essayed a conversation with them, but made a signal of failure, as after listening to a few sentences in Spanish and English, they seized their acorn baskets and ran. The glimpse we had taken of these mountain beauties, and our failure to enter into any conversation with them, determined us to pay a visit to their headquarters, which we knew were near by. Watching their footsteps in their rapid flight, we saw them, after descending a hill, turn up a ravine and disappear. We followed in the direction which they had taken, and soon reached the Indian Rancheria. It was located on both sides of a deep ravine, across which was thrown a large log as abridge, and consisted of about twenty circular wigwams, built of brush, plastered with mud, and capable of containing three or four persons. As we entered, we observed our flying beauties, seated on the ground, pounding acorns on a large rock indented with holes similar to those which so puzzled me at Camp Beautiful. We were suddenly surrounded upon our entrance ty thirty or forty mail Indians, entirely naked, who had their bows and quivers slung over their shoulders, and who stared most suspiciously at us and our rifles. Finding one of them who spoke Spanish, I entered into conversation with him told him we had only com to pay a visit to the Rancheria and, as a token of peace offering, gave him about two pounds of musty bread and some tobacco which I happened to have in my game-bag. This pleased him highly, and from that moment till we left, PuIe-u-le, as he informed me his name was, appeared my most intimate and sworn friend. I apologized to him for the unfortunate fright which we had caused a portion of his household, and assured him that no harm was intended, as I entertained the greatest respect for the ladies of his tribe whom I considered far superior in point of ornament, taste, and natural beauty to those of any other race of Indians in the country. PuIe-u-le exhibited to me the interior of several of the wigwams, which were nicely thatched with sprigs of pine and cypress, while the matting of the same material covered the bottom. During our presence our two female attractions had retired into one of the wigwams, into which PuIe-u-le piloted us, where I found some four of five squaws similarly bepitched and clothed, and who appeared exceedingly frightened at our entrance. But PuIe-u-le explained that we were friends, and mentioned the high estimation in which I held them, which so pleased them that one of the runaways left the wigwam and soon brought me in a large piece of bread made of acorns, which to my taste was of a much more excellent flavor than musty hard bread.

PuIe-u-le showed us the bows and arrows, and never have I seen more beautiful specimens of workmanship. The bows were some three feet long, but very elastic and some of them beautifully carved, and strung with the intestines of birds. The arrows were about eighteen inches in length, accurately feathered, and headed with a perfectly clear and transparent green crystal, of a king which I have never before seen, notched on the sides and sharp as a needle at the point. The arrows, of which each Indian had at least twenty, were carried in a quiver made of coyote skin.

I asked PuIe-u-le if he had ever know the existence of gold prior to the entrance of white men into the mines. His reply was that, where he was born, about forty miles higher up the river, he had, when a boy, picked it from rocks in large pieces, and amused himself by throwing them into the river as he would pebbles. A portion of the tribe go daily to the Yuba River, and wash out a sufficient amount of gold to purchase a few pounds of flour, or some sweetmeats, and return to the Rancheria at night to share it with their neighbours; who in their turn go the next, while the others chasing hare and deer over the hills. There were no signs around them of the slightest attempt to cultivate the soil. Their only furniture consisted of woven baskets and earthen jars, and PuIe-u-le told me that in the spring he thought they should all leave and go over the “big mountain” to get from the sight of the white man.

From Roland Dixon’s book “The Northern Maidu”, the Native Americans that Buffum encounterd would have been from the Nishinam of Powers tribe, also referred to as Tan’koma. There is no mention in Buffum’s account if the purported grave that he encountered was connected to the group of Native Americans he encountered. There was quite a distance between the two encounters. Roland does describe the burial of the Northeastern Maidu which has similarities to what Buffum saw, except the grave site was not in the Northeastern Maidu territory.

“If the person were a chief or shaman, then wands (yo’koli), or sticks with pendant feathers were set up on over the grave.” Page 244.

Roland also describes how women of a deceased husband would mourn by cutting her hair short and being covered in dark pine-pitch.

“In mourning, the widow cut her hair short, and covered her head, face, neck, and breast with a mixture of pine-pitch and charcoal obtained from charring the wild-nutmeg or pepper-nut. This pitch she was obliged to wear until it came off, generally many months.”

But Native American women would wear the stripes or whiskers for other occasions also. Perhaps someone with more training and research into the customs and habits of Native Americans in this region can shed more like on Buffum’s descriptions.