It was an 1881 trial that, in retrospect, became an oral history of early California pioneers describing the landscape of Sacramento in 1849. The court action in question was The People vs. The Gold Run Ditch and Mining Company. The accusation was that the Gold Run Mining Company, through their hydraulic mining on Indiana Hill in Placer County, was filling the American River, and subsequently the Sacramento River, with mining debris. This mining debris was destroying farms and, from the perspective of Sacramento City, causing their nascent sewer system to fail, leading to disease.

By the 1870s, a tremendous amount of hydraulic mining debris had washed down from the north, middle, and south forks of the American River. Successive flooding events had pushed the sand and silt over the small levees protecting Sacramento City and many parts of the county. Without photographs or reliable illustrations of the landscape and topography of Sacramento in 1849, lead counsel for the plaintiff, Attorney General Hart, relied on eyewitness testimony to paint a picture of Sacramento in 1849.

Eye Witness Testimony of Early Sacramento Landscape

The lead defense attorney, Amos P. Catlin, also relied on early pioneers to California to help make his case that Sacramento had suffered very little injury from hydraulic mining debris. Two of the more famous witnesses in the trial were General John Bidwell and James Marshall who each came to California before 1849. Of the men called to testify, twenty-four arrived in 1849, twenty-two came in 1850, two were from 1851, five in 1852, nine landed in 1853, five passed through in 1854, with another eleven men who came to California in the years 1855 – 1862.

The point of the eye witness testimony was to compare and contrast the state of the rivers and topography in the years prior to the great floods of 1861 – 62, to the condition Sacramento had become in 1881.

The trial opened in mid-November 1881 and would close in early March 1882. There would be 58 days of testimony before visiting Superior Court Judge Jackson Temple from Sonoma County. In addition to the 69 different eye witness accounts, there would be several other expert witnesses ranging from civil engineers to physicians. For this review of the debris trial, I read through the reports of the local newspapers plus the closing arguments published in the Sacramento Daily Union. A court transcript exists at the California State Archives and I have read through the original testimony of Benjamin Bugbey from the trial.

Clear Water At the Confluence of Sacramento and American Rivers

While the larger picture presented at the trial revolves around the hydraulic debris, also referred to as slickens, and its impact in the American and Sacramento rivers, we also get early historical accounts of the confluence of these two rivers and the native landscape. Not in dispute were many characteristics of the Sacramento and American rivers in 1849. The American was a river that had clear water. Many pioneers spoke of crossing the American at Lisle’s bridge across a river bed of small gravel and pebbles.

The banks of the Sacramento and American rivers were 15 to 20 feet high at low water levels. Large ocean-going vessels of 300 tons and steam boats could easily navigate the Sacramento River that had water depths of 22 to 26 feet. Both the Sacramento and American rivers were subject to tidal influence through the 1850s.

I have known the American River from its mouth five or six mile since the fall of 1856. It flowed at that time through well-defined banks. It was 400 feet wide, or wider, at the mouth. It had abrupt banks at low-water 20 feet high. There were settlements on the banks. On the north bank there were several groves of oak trees. On Milgate’s and Bannon’s places there were beautiful groves. The grove at Milgate’s was often the scene of picnics. On the south side for three-quarters of a mile was a slough coming from the American River and emptying back again into the same, making an island. This island was covered with a growth of cottonwood. Large trees of oak, some of them containing several cords of wood, and also some sycamore trees fringed the banks. There was a lake near the mouth of the river where the railroad shops now stand. There was also another lake extending from Sixth street to Mr. Rider’s.

Testimony of A. S. Greenlaw

The relatively deep water and high banks gave the new inhabitants of Sacramento a false sense of security until the floods of 1850. Even after those floods, the city of Sacramento only established modest levees on the north side of the city to check the flow from the American river. It was the American River that posed the greatest risk to the city with a network of sloughs that crept into the city from the northeast side. After many men had either made their money mining, or gone bust, several turned to agricultural pursuits. In the 1850s orchards and vegetable gardens, especially north of B street sprouted up.

Many of the men recounted how they noticed the clear waters of the American River becoming colored or muddy beginning in 1853. This coincides with the time when water canals were built on the North and South Forks of the American River. With the placer gold virtually mined from the river bed, the miners turned to the banks and benches for gold. The water canals – Bear River Ditch, North Fork Ditch, and Natoma Canal – allowed miners to begin sluicing the banks for gold.

Hydraulic Mining Begins on the American River

William Gwynn came to California in 1849 and sold mining supplies and also ran a mining company. He traveled up and down the different forks of the American River. At one point he employed 300 men working at Oregon Bar on the North Fork. Gwynn estimated that there was a minimum of 10,000 men mining on the American River forks by 1851. The first hydraulic mining he witnessed was at Rattlesnake Bar running water from the Bear River Ditch into and iron pipe and directing the stream through a duck hose at about 55 feet of head in 1854.

Hydraulic mining was in its infancy in 1854 and it would only grow bigger. Most people in Sacramento City grumbled about the poor water quality of the American River, but viewed it as a necessary evil for the sake of the mining economy. However, in 1862, life in Sacramento would be altered forever with a horrendous flood. Cold rain storms in 1861 caused the usual localized flooding events and reminded Sacramento that they needed to reinforce the levees.

Flood of 1862 and Hydraulic Mining Debris

In the winter of 1862, a series of warm storms not only produce torrential rain, it melted the snow in the Sierras. The result was an inundation of flood waters that turned the Central Valley into a lake. Many witnesses spoke of piloting steam boats to the east of Sacramento City to a point called Hoboken. When the waters finally receded land owners saw their property covered with sand.

Judge George Cone lived on the north side of the American River and testified that the 1862 floods deposited several feet of sand on his land. Sidney Smith of Smith’s Gardens on the south side of the American River reported one to six feet of sand on land after the flood. Joseph Routier spoke of his property before and after the floods.

In the early days the country in this locality was the most beautiful and picturesque I ever beheld. The banks were fringed with fine groves of white oak, live oak, shrubs, and beautiful flowers of every form, hue, and variety. The river banks were high, abrupt, showed no signs of wash, on the contrary, there were covered with moss and fern.

Testimony of Joseph Routier

After the flooding of 1862, Routier reported that only 300 out of 3,000 orchard trees had survived. The rest were smothered in sand. He reported that the bed of the American River at his property had risen 26 feet in the ensuing years.

Peter Spencer who lived at B and 22nd street noted the flood of ’62 left six to twelves of sand on his farm. John Rooney, who was living in Brighton, just east of Sacramento, said he had no problems with flooding until 1862. He had 800 acres primarily in grain and alfalfa that were covered with sand and silt.

Several of the men testified they watched the torrential flood waters come down the American River. The water was brown with mud and sand. A few of the men described the turgid waters as slumgullion, which was a cheap watery beef stew. There were waves in the river six feet high. A couple of the men took water samples with buckets. After the water had settled, some reported an inch of sand in the buckets. W. S. Manlove surmised from his observations that upwards of a sixth of the volume of the flood waters was sand and silt.

American River Is Moved North

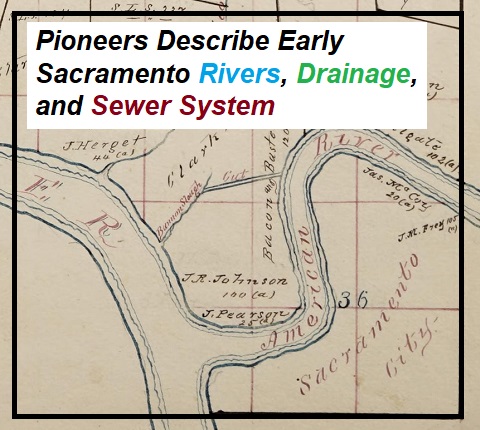

After the flood of 1862, the city of Sacramento lobbied the Legislature to move the mouth of the American River north. The Act was passed in 1863, and by 1867 the American River had been straightened and now emptied three-quarters of mile north of the original mouth. This was accomplished by making two cuts next to Bannon Slough to connect the American with the Sacramento at that location.

The results were almost immediately felt in 1868 with another flooding event. This time, not only was Sacramento impacted, the force of the American River, no longer corralled by bends in its course, shot straight across the Sacramento River and overwhelmed the small levees on the Yolo County side of the Sacramento River. The little town of Washington was devastated. In addition, the flood of 1868 deposited several feet of sand and silt in what would be West Sacramento.

Slickens Invades Sacramento

The 1868 floods also brought another element of mining debris down with the sand and silt; slickens. As the name implies, this yellowish-brown mineral deposit is slick when wet. It is primarily clay washed down from the hydraulic mines. James Holland, who lived near Lisle’s Bridge, described the slickens.

The sediment that I spoke of as slickens is a finer material, and when wet is very sticky, and a person cannot walk through it then. When dry it cracks, and I have seen cracks that I could put a stick down in for four or five feet. This slickens will produce a fine crop of willows, but will produce nothing else. After being exposed to the sun for a few years and well plowed, you can raise a partial crop, but it is nothing compared with the old soil.

Testimony of James Holland

Holland also testified that since 1868 he has been getting more and more mining waste on his property during river overflows on either side of the Marysville Road south of the American River. He said, “The water comes right across twelfth street and empties into China Slough.”

Sacramento River Gets Shallow

The original mouth of the American River was very wide and deep. It made a natural small bay for ships to anchor. Many vessels visited Pioneer Mills which was on the original mouth of the American River. After the flood of 1868, a large sand bar was created in front of the old mouth of the American River. John Hoagland testified that he could no longer see the original mouth of the river from the Yolo County side.

River boat pilots Captain John H. Roberts and Captain Enos Fouratt testified they started encountering more shoals and drifting sand bars in the Sacramento River after 1866. Fouratt described his experience on the Sacramento beginning in 1849.

The river when I first came to the State was as clear and beautiful a stream as I ever beheld. In early days you could not see much of the tule basin. At present you can see it from the boats very plainly. I have seen black sand in considerable quantities at Haycock shoals. In 1871 I was Captain and pilot of the Yosemite, and grounded on these shoals. I do not recollect having any trouble on those shoals during the year 1864.

Testimony of Captain Enos Fouratt

As the Sacramento filled with mining debris, land owners and reclamation districts built higher levees. This meant the water elevation was higher in the river channel allowing Fouratt, and other passengers, to see across the tule basins they were traveling next to. Captain Hodgdon reported that the average depth of the Sacramento River in front of Sacramento City had shrunk from 22 feet down to 7 feet. Several men noted that because of the large amount of sand in the Sacramento river, there was no longer any tidal influence.

The central focus of the hydraulic mining debris trial was the injury caused to agricultural land. Many farmers reported that the several feet of sand and debris deposit by floods rendered their property unfit for agricultural purposes. In addition, most witnesses testified the American River, flowing in 1881, was unfit for potable purposes.

Some Farmers Welcome Mining Debris

The defense argued that the mining debris had many beneficial qualities. Civil engineer L. C. McAffee testified that the peat soils used around the delta islands were not strong enough. The sand and sediment washed down from the mines made much better levees for holding back the water of the Sacramento River.

Washington Fern, who had been farming south of Sacramento since 1852, reported the sand and silt actually improved part of his land. A levee break poured water and debris across tule land he owned for six weeks near Willow Slough and Hooker Lake. The sand turned the tule land into usable farm acreage.

Another point the defense raised was that Sacramento was routinely subject to monumental flooding in the valley. They brought in James Marshall to recount how he had heard from inhabitants prior to his arrival in California of a great flood in 1830. He believed it because he saw driftwood lodged high in the branches of trees. To counter Marshall’s testimony, General John Bidwell was sworn in and testified he had also heard the tall tales from Captain Armington about great floods and did not necessarily believe them.

Engineers Survey Hydraulic Mine Debris

Several civil engineers and doctors testified for the defense. By modern scientific standards, their testimony seems almost comical. Of course, the microscopic world of viruses and bacteria was only just emerging. Myths of how diseases were harbored in the soil and water, along with transmission vectors, were still widely held as scientific fact.

A point of dispute was how much mining debris from the Gold Run Mine ultimately flowed into and down the American River. The North Fork of the American River canyon is very rugged and nearly impassible on horseback. Consequently, some of the engineers, such as G. F. Allardt, calculated distances by how long it took their horses walk from one point to the next on the trail. As to the depth of the mining debris in the river bed, one of the engineers remarked that he had very good eye sight.

Of the more reputable estimates of debris came from William Hammond Hall, a civil engineer with the State of California. He estimated the mine tailings created from washing off large portions of Indiana Hill, site of the Gold Run operations, would be the equivalent of a pile of debris 2.5 miles long, 200 yards wide, and 30 yards deep. It would cover approximately 500 acres and be equal 26 million cubic yards of material.

One of the more dubious claims by the defense was that the mining waste, because of its chemical composition, would become cemented in the American River. Chemist and hydraulic engineer Thomas Price stated that the debris from the mine would recement in the bed of the American River and very little would ever reach the Sacramento River.

What was indisputable was that the mining debris filling the American and Sacramento Rivers was not solely from the Gold Run mine. There was extensive testimony about the sluice mining along the American River with detailed accounts of how whole hills had been mined with water. John Lawton noted how at least 150 acres of Negro Hill, just upstream of Mormon Island, had been washed away. Benjamin Bugbey similarly identified Texas Hill, west of Negro Bar, as having been completely sluiced down to cobble stones.

The defense also introduced the prospect that erosion from farms, roads, cattle ranching, and forestry operations also contributed to soil and sand in the waterways. One fanciful concept was offered by M. D. Fairchild who asserted that frost was a leading culprit to debris in the rivers. The Sacramento Daily Union wrote, “Witness produced a sample of material taken from one superficial foot of ground near Mt. Gregory. The material in question was elevated two inches above the surface, resting on ice and forming a crest.” The environmental action described was most likely needle ice. As soil water evaporates it comes into contact with freezing air, and can lift a small portion of soil on what looks like a bed of needles.

State of the Sacramento Sewer System

One of the accusations against the Gold Run Mining and Water Company was that their mining debris was creating unsanitary conditions in the City of Sacramento. The floods prolonged damp soil, the water table was higher because the rivers were now elevated in their channels, and the debris was choking off drainage points in the city. Professor Price, in preparation for the trial, also examined the City of Sacramento’s sewer system, which at the time, was little more than a septic leach field under the streets.

Price found that many of the sewer pipes were made of wood and others were of non-mortared brick lining. He also noted that many of the water closets and cesspools were not connected to the city drainage system that handled both sewage and storm water runoff. Price reported the average waste creation as being 25 tons of fecal matter and 91,250 gallons of urine per 1,000 people per year. Sacramento City in 1879 had a population of approximately 50,000, although most of them were not served by the limited sewer/drainage system at the time.

Amos Catlin Defense Attorney

Amos Catlin, lead attorney for the Gold Run Ditch and Mining Company, was a Gold Rush ’49er himself. He set up mining at Mormon Island shortly after he arrived in California from New York. He also helped organize the Natoma Water and Mining Company that built the Natoma Ditch on the South Fork of the American River, and the American River Water and Mining Company that constructed the North Fork Ditch on the North Fork of the American River. He had mining and the interests of the miners in his blood.

However, Catlin was an attorney, very much well respected in Sacramento. In 1877 he represented George Atkinson, a farmer on the Cosumnes River, in a lawsuit against the Sacramento and Amador Canal Company. The issue was the same, mining debris from the canal company’s operation, which flowed into the Cosumnes River, was deposited on Atkinson’s land during a flood. Catlin won the lawsuit and Atkinson was awarded $4,000 in damages.

Catlin loved Sacramento, he called it home. His law practice was so lucrative that he could have moved to the Bay area where the weather was cooler and he frequently vacationed at. As a State Senator in 1854, Catlin sponsored legislation that moved California’s capitol permanently to Sacramento. Unfortunately, Sacramento, even with the title of the State’s capitol, was struggling to put together a real sewer system. (Learn more about A. P. Catlin)

Was It a Sewer or Drainage System?

Dr. G. L Simmons, who arrived in California in 1850, stated that typho-malaria cases had increased in the last 12 years. He noted, “Cesspools for kitchen drainage are dug to a depth of about eight feet. Most of these cesspools are made of open brick work, which admits the contents being largely absorbed by the subsoil.” Because of the rising water table of Sacramento, the contents, bacteria – and as we know today nitrates – are introduced into the ground water through these unlined cesspools. Plus, some residents still maintained drinking water wells at their homes in the city.

It was the lack of a credible sewer system, Catlin claimed, that was leading to typhus cases and other diseases in the city, not the mining debris. Former Street Commission W. F. Knox described the incomplete drainage plan for Sacramento. The plan was to take the open sewage/drainage canal on the south side of R street and run it down to Snodgrass Slough. The city had cut a canal 20 feet deep and 50 feet wide, but the canal stopped at Beach’s Lake.

In Catlin’s closing argument, it is if he is putting the City of Sacramento on trial for their municipal failures relative to sewers and drainage.

“Mr. Knox says there were no sewers here before 1862 except little boxes across the streets that had been filled, and none outside of the mainly populated portion of the city – I street, J street, and K street, running up to Eleventh and Twelfth.”

“They complain that the sewerage of this city has been destroyed. Some of the witnesses who spoke upon that subject did not understand what our “sewerage system,” so-called, was; but they assumed that we had a system of sewerage. I do not think it is necessary to recur to that portion of the testimony in detail.”

“There are only six sewers – and we will call them sewers now for the purpose the argument – running through this city from north to south. That large portion of the city east of Thirteenth street has no sewerage at all, and a very large portion of the inhabitants of this city reside above that street. We are standing on Eleventh street now, and there is no sewer through this street. There is no other sewer until we reach Ninth street, and then there are sewers running through Seventh, Fifth, and Third, and in the alley between Front and Second streets, making six in all which run to R street. Those above Sixth street turn at a right angle on R street and run west to Sixth, and those below Sixth street turn on a like angle at R street and run east to Sixth. They unite at Sixth and R streets, and there pass into the drainage canal……”

“There are also the lateral sewers between these odd number streets which connect with this main sewer, and they are generally made of wood. Some of the main sewers are also of wood and some are of brick, but they are constructed generally with open work on the bottom and sides.”

“Instead of the sewers of this city being constructed as sewers are constructed in every city we have ever heard of – constructed for the purpose of confining and carrying away the foul waters to some proper receptacle – these sewers are made expressly to distribute their foul contents in the soil of the city as widely as possible. Perhaps that was a necessity, although it does not seem to me to be so, because no solid or fecal matter is discharged into these sewers, or these drains which we call sewers. The city authorities have strictly adhered to the policy, if it is a policy, of having all the matter sink into the soil upon which the city is built, to saturate it, permeate it, and fester there and breed disease. And a city having a system of sewers like that comes into Court here in the name of the People of the State and complains that we have destroyed its sewerage system. Well, such a sewerage system as that ought to be destroyed. It never ought to be allowed to exist.”

Catlin also took the city to task for straightening out the American River. If not for this re-alignment of the American River, Yolo County might have been spared horrendous flooding. It was the new outlet of the American River into the Sacramento River that had caused so much devastation to Yolo County, not the mining debris.

“…[W]e find that the American River…of 1849-50…it approached the city by a circuitous route… It made three large bends to the north and northwest of the city. It came, in nearly a southerly course, directly toward the city, striking our northern boundary at a point known to fame in our early history as Rabel’s Tannery; then turning with a sharp bend away to the west and northwest, and coming back again, after making two more bends, with a gentle curve entered the Sacramento River at a very oblique angle near where the Pioneer Mills now are.”

“…[T]he city, under authority of an Act of the Legislature, straightened the river channel by means of two cut-offs, and removed its mouth three-quarters of a mile further north. That improvement shortened the channel nearly two miles, and made the American strike the Sacramento point blank at right angles, at a distance of about three-quarters of a mile above its old mouth.”

“They have told us how the American River in 1868 tore its way across the Sacramento river into Yolo County, destroying levees, natural river banks, orchards, houses, and lands.”

Sacramento County Supervisor Opposition

This debris trial, and many others like it, were about the economic soul and identity of California. Sacramento County Supervisor Edward Christy admitted that he was adamantly opposed to the lawsuit. Even though he acknowledged that the American River west of Folsom was clogged with 15 to 20 feet of debris for 4 miles, he reckoned that if there was no mining there were no jobs. He also didn’t like Sacramento County appropriating $12,000 for attorney fees to prosecute the case.

It was Custom to Dump Mining Debris in Rivers

There were also seemingly inherent contradictions on the part of the mining community with respect to their actions. As G. H. Colby, a surveyor from Dutch Flat stated, “It has always been the custom to dump (tailings) into the streams, gulches, ravines, flats where the flats were not owned by anybody. That has been a uniform custom all over the State…miners cannot work gravel claims without a privilege of that kind.” But he would follow up with the statement, “One miner would never claim the right to pile his rock on his neighbor’s claim, to the latter’s injury.”

If a miner would never dump his mining debris on a neighbor’s mining claim, why should the miner be exempt from the injury caused by their debris fouling farm land? The answer was given by Judge Temple in June, the mining community did not have immunity from the damage their debris caused. Judge Temple ruled that hydraulic mining injured navigable waterways and contributed to unsanitary conditions in Sacramento City.

The Gold Run Ditch case would not be the end of the fight against hydraulic mining. The final chapter was written when U. S. Circuit Court Judge Lorenzo Sawyer ruled against the North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company and in favor of central valley farmers affected by hydraulic mining debris the company dumped into the Yuba River. This ruling effectively stopped hydraulic mining except for those mines who could contain their waste or when the deposits did not affect property or navigable water ways.

Overall, the testimony given in People v Gold Run Ditch and Mining Company provide an interesting oral history from early pioneers about the state of Sacramento City, the Sacramento and American Rivers, and the mining that took place in Sacramento, Placer, and El Dorado counties. The actual court transcript is thousands of pages long. The newspaper reports only capture a sliver of the granular testimony. The examination and cross examination of witnesses reveals any more information about the individuals and the local history.

Cross Examination

This is just a small snippet of the cross examination of Benjamin Bugbey by his old acquaintance Amos Catlin.

Q. Where was it that you were engaged in mining for ten months, at what place?

A. At Condemned Bar on the North Fork, on Little Oregon Bar about half mile above Beal’s on the North Fork, at Big Gulch Bar opposite Folsom and on Negro Bar.

Q. How long were you engaged on Negro Bar?

A. On Negro Bar I do not think that I worked there over six weeks.

Q. In what year?

A. The spring of 1850, I had been working the opposite side of the river previous to that.

Q. You say there were no quantity [of] pebbles in the earth that constitutes the formation of Negro Bar?

A. I said there was none not any considerable amount noticeable on the surface of the bar in those days, not after 1862.

Q. You say that there was no considerable amount noticeable on the surface?

A. On the surface as there is now.

Q. Then you do say that there were no quartz pebbles in the earth, that was excavated from mining purposes on Negro Bar in 1850?

A. No, I said that now there are quartz pebbles covered on the surface.

Q. What do you say to my question now, were there or were there not quartz pebbles in the earth which the miners worked from mining purposes on Negro Bar in 1850?

A. They are scarce, You —— —— some.

Q. What mine were you interested in for a period of 2 years that you mentioned?

A. 18 months.

Q. Where were the situated?

A. A little ——- of 18 months, I was going to answer the question by dividing it up, about 18 months of the two years, I was engaged in mining – drifting, the mine ran in block 40 in the town of Folsom fronting Negro Bar, we ran our tunnels out to the water.

Q. On the other bank?

A. Yes sir, where the town plot is.

Q. Where Folsom now is?

A. Yes sir, on the lower flat of Folsom.

Q. A considerable part of the town is now situated there?

A. Yes sir, we ran tunnels in through and excavated underneath, piling our cobbles up inside, and running our pay dirt out.

Q. You did not include that flat in what was call Negro Bar?

A. No sir, that is above Negro Bar, it faces Negro Bar.

Q. What is your occupation now?

A. I am now introducing a patent right, I am living at Folsom, however engaged in a small degree in fruit raising.

Q. Fruit raising and introducing a patent, right?

A. Yes sir, introducing a refrigerator.

As you can read, the examination can yield some detailed answers about history. But converting the microfilm transcript into format we can all study, is a project for another day.

List of Pioneer Witnesses

Partial list of men who testified at the debris trial and the date of arrival in California.

- General John Bidwell, 1841

- James Marshall, 1845

1849

- Harford Anderson

- N. Babcock

- Benjamin Bugbey

- Captain Albert Foster

- E. H. Evens

- Judge James Galloway

- J. B. Green

- William Gwynn

- J. E. Hale

- N. Hoag

- John Hoagland

- Captain Hodgdon

- Hezekiah P. Jones

- R. P. Johnson

- Senator William Johnston

- J. H. Keown

- W. F. Knox

- W. S. Mesick

- O. N. Morse

- Lewis Posy

- P. M. Randal

- Judge Nile Searls

- O. P. Stidger

- John B. Taylor

1850

- George Blanchard

- David L. Bowers

- H. H. Brown

- Marion Biggs, Sr.

- C. W. Clark

- G. H. Colby

- John S. Colgove

- M. D. Fairchild

- Captain John R. Ferris

- Captain Enos Fouratt

- W. S. Green

- Judge Archibald Henley

- James Holland

- A. Howard

- N. A. Kidder

- Captain John H. Roberts

- John Rooney

- R. G. Sneath

- J. F. Talbot

- Eli Wells

- Daniel Webster

- William White

1851

- John Lawton

- George Little

1852

- Edward Christy

- Judge George Cone

- Washington Fern

- W. S. Manlove

- Peyton Powell

1853

- F. B. Granger

- Samuel B. Harriman

- Dr. F. W. Hatch

- L. Hodge

- Fermen Hoxie

- John McBeth

- Joseph Routier

- Peter Spencer

- Rudolf Wittenbeck

1854

- Anthony Clark

- Charles Carr

- James O’Brien

- L. L. Robinson

- Sidney Smith

1855 – 1862

- S. Greenlaw, 1855

- L. Ecklon, 1856

- John Rider, 1856

- Walter Skidmore, 1857

- John Shafer, 1858

- Dr. James Simpson, 1858

- George Swingle, 1858

- John Hobson, 1859

- John C. Green, 1861

- Thomas McConnel, 1862

- Thomas Price, 1862

Source material is from newspaper accounts found on the California Digital Newspaper Collection, California State Archives, Center for Sacramento History, Library of Congress, Sacramento County Assessor Book Maps. If you are interested in specific dates, please contact me.