The Stockton Independent newspaper put it best with an article about the Leidesdorff land grant titled The Grant Curse. A sizeable portion of Spanish and Mexican land grants in California seemed to be cursed with endless rounds of litigation to determine their authenticity and boundaries. The Leidesdorff Mexican land grant, Rancho Rio de los Americanos, was no different. The original map, delineating the boundaries of the Leidesdorff land grant of 1844, was finally sustained by the U. S. Supreme Court in 1864. Central to the survey of the land grant was an oak tree on the banks of the American River.

In March of 1848, William Alexander Leidesdorff proclaimed, “…there’s no law here but club law…” Leidesdorff was explaining to the Alcalde of San Francisco why he carried a pistol and was prepared to use it on anyone who insulted him. Since the Mexican government had been defeated by the United States, and no official provisional government had been established, California was operating almost in a state of government limbo.

Leidesdorff Land Grant

Leidesdorff, of mixed Danish and Caribbean descent, arrived in California in 1841 at the age of 31. His primary business was shipping at Yerba Buena. He became a Mexican citizen in 1844 and received a land grant from Mexican Governor Micheltorena of 35,000 acres south of the American River next to John Sutter’s grant. Under the terms of the land grant, Leidesdorff had to build a residence on his Rancho de los Americanos land grant. He built the abode, but his primary focus was on the emerging community of San Francisco.

On May 18, 1848, Leidesdorff died in San Francisco. He died not from any gun fight but from a virus or bacterial infection. On May 20, a notice ran in the local newspaper that Charles Meyer had been appointed by the presiding U. S. military governor Colonel Mason to settle Leidesdorff’s estate. All inquiries regarding the estate were to be received by Captain J. L. Folsom, Assistant Quarter Master.

Another army officer that had come to California was Henry Halleck. General Bennet Riley, the next military governor after Mason, appointed Halleck Secretary of State. Halleck was college educated and liked to research and write on historical topics. He was instrumental – some would say influential – as he assisted California’s first elected delegates to draft a state constitution in 1849. It was proposed during California’s first legislature to employ Halleck to translate all of the Spanish and Mexican land grants since they rested with General Riley and were under Halleck’s control. The lack of funds, as the newly declared state had no taxing authority and was not recognized by the federal government, precluded any serious analysis of the land grants.

After gold was discovered in 1848, California was flooded with miners in 1849. Property boundaries were pretty much ignored. One of the men who took advantage of the chaos, better known as the Gold Rush, was Amos P. Catlin who came from New York. He started mining at Mormon Island in 1849 on the South Fork of the American River and then organized the Natoma Water and Mining Company in 1852. The water canals that the Natoma Company built traversed over the Leidesdorff land grant. Of course, there was no official map of the Leidesdorff property or even California at that point.

Captain Folsom Acquires Leidesdorff Estate

Captain Folsom took a leave of absence from the army, tracked down William Leidesdorff’s mother, Anna Sparks, in the Caribbean, and got her power of attorney to handle William’s estate. In February 1850, represented by the new law firm formed by Henry Halleck (Halleck, Peachy & Billings), Folsom was awarded the administration of the Leidesdorff estate. By April 1850, Folsom is running notices in the local newspapers that boundaries of the Rancho Rio de los Americanos must be respected, no trespassing without permission, and no cutting of timber. The main road from Sacramento up to the mining regions on the South Fork of the American River ran through the Leidesdorff land grant. Folsom let the existing hotel keepers stay, but rental terms would be negotiated in the future.

By July 1850, Folsom’s carefully crafted takeover of the Leidesdorff estate began to get swamped by the governing muck that passed for government before California became a state. Judge Morrison of San Francisco determined that Folsom was not legally entitled to be the Leidesdorff estate administrator. Folsom got that decision overturned. Judge Morrison was then investigated for corruption regarding his initial Leidesdorff estate decision against Folsom.

The focus on the Leidesdorff estate, and who would control it, was over the prime San Francisco real estate valued at approximately $800,000. After California became a state in September 1850, the legislature started introducing bills to recover the Leidesdorff estate. California, by this time, was heavily in debt and no one wanted to pay taxes. At the state level, there was a move to acquire the Leidesdorff estate by escheat provisions, that had not been enacted. Escheat is the reversion of property back to the state when the owner dies without leaving any heirs.

In what turns out to be early California fashion, everyone proceeds on their own course ignoring, as best they can, protestations of other parties. All of this confusion and uncertainty was generated by Congress and California who failed to act by setting up a territorial government, comprehensive survey and maps of land grants, and a proper process for adjudicating the claims of land grant owners. This would plague California for decades, even ensnarling the legitimacy of the Sutter land grant.

California Attempts to Seize Leidesdorff Estate from Folsom

By 1853, California had finally gotten around to setting up a land commission to parse out the titles and maps. Governor Bigler encouraged the Board of California Land Commissioners to seize the Leidesdorff property. In April 1854, the land commissioners took up the investigation and examination of the Leidesdorff estate. With a decision imminent in summer of 1855 and high anxiety over land titles, a group of settlers and miners in Prairie City, just inside the Leidesdoff grant, met and urged the State of California to take over the Leidesdorff estate.

A few days after the settler’s and miner’s meeting in June 1855, the land commissioners issued their opinion confirming the claim of Folsom to eight leagues of land in Sacramento County known as the Leidesdorff land grant. Eight leagues converted to 35,509 acres. All that was left to do was create a map of Rancho Rio de los Americanos. Unfortunately, Joseph L. Folsom would die the next month on July 19, 1855. Halleck, Peachy & Billings became the executors of the Folsom estate and A. H. Jones, U. S. Deputy Surveyor, begins mapping the land grant in Sacramento County. The final map would be known as the Hays survey as John Coffee Hays was the appointed U. S. Surveyor-General in California.

By today’s standards, it seems absolutely crazy that anyone would invest money in property or infrastructure when there was no clear title to the land and the State of California continually threatened to strip Folsom of his ownership of the Leidesdorff estate. But this was the state of California in the 1850s. Even before the untimely death of Folsom, he and other men were pushing forward with their development plans in Sacramento County. Folsom had been working with the Sacramento Valley Railroad to run a line from Sacramento to Negro Bar on the south side of the American River over the Leidesdorff land grant.

In early 1855, with the railroad short on capital to complete the road, Folsom took the helm of the company to raise money and keep building. In 1853, Amos Catlin, who was now the president of the Natoma Water and Mining Company, had bought shares in the Sacramento Valley Railroad and was named a director. From Catlin’s involvement in the railroad, he would have been familiar with Capt. Folsom. Catlin’s Natoma Water and Mining Company continued with their water ditch expansion to deliver water to miners and farmers into Sacramento County and across the Leidesdorff land grant.

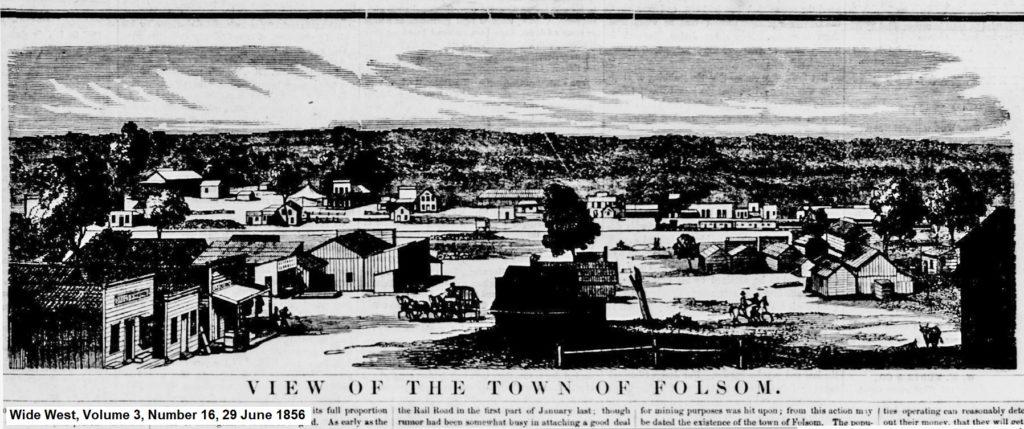

The terminus of the Sacramento Valley Railroad, above Negro Bar on the American River, was to be named Granite City, a town laid out by Theodore Judah. After Folsom died, the executors of the estate renamed it Folsom. Amos Catlin bought several lots in the new town. As Catlin and others were buying the new Folsom town lots, there were a group of squatters that denied the validity of the Leidesdorff claim. The map of the Leidesdorff land grant had not been released and it was unclear if the newly minted town was even in the boundaries of the Rancho Rio de los Americanos, although, most people assumed it was.

At a meeting of miners, who had staked claims along the American River and South Fork of the American River, the miners declared they were not in the boundaries of the Leidesdorff land grant. They resolved to fight any map that included their claims in the land grant. The position must have been the miners would rather file a preemption claim with the federal government, than deal with the executors of the Folsom estate for property and mineral rights.

Hay’s Survey of Leidesdorff’s Land Grant

In May 1857, the official map of the Rancho Rio de los Americanos was released. While the original land grant came with a crude map, included in the documentation were the actual measurements of the land grant. (One league is approximately 2.6 miles.)

Beginning at an oak tree on the bank of the American River, marked as a boundary to the lands granted to John A. Sutter, and running thence south with the line of said Sutter two leagues, thence easterly, by lines parallel with the general direction of the said American River, and at the distance, as near as may be, of two leagues therefrom, four leagues, or so far as may be necessary to include in the tract the quantity of eight square leagues, thence northerly, by a line parallel to the one above-described, to the American River; thence along the southern bank of said river, and bending thereon to the point of beginning.

The old oak tree, then residing near A. D. Patterson’s barnyard, and marking the eastern end of the Sutter land grant, was the only specific marker other than the river. As for an eastern reference for the boundary, the land grant cited the lomerias. In Spanish, lomeria translates into low hills. What came to be disputed was where the lomerias started. On the 1844 map was a small line indicating a creek. This was taken by the opponents of the new Rancho Rio de los Americanos survey as Alder Creek and the beginning of the lomerias.

If Alder Creek was the beginning of the lomerias or eastern boundary of the land grant, it would shorten the width by two miles. The shortened width would have excluded the town of Folsom. Because the northern boundary was set by the American River, in order to achieve the full eight leagues of land mass, the southern boundary would have to be extended. A southern boundary expansion did not please those settlers who were certain they were not in the land grant.

The narrower land grant proportions would not have made much difference to the Natomas Water and Mining Company if they had not already bought some of the property from the Folsom estate. In a letter to the Sacramento Union to defend the operations of the Natoma Water and Mining Company, President Amos Catlin outlined how Captain Folsom instructed his attorneys to commence action against the Natoma Company for rents on the Natoma water canals on his Leidesdorff land grant. Folsom was demanding over one-third of the gross receipts of the water sales and an injunction against future use of the water canal right-of-way.

As a compromise, the Natoma Water and Mining Company purchased 9,000 acres of land from Folsom that encompassed their water canal operations. The purchase, at $4 per acre or $36,000, went all the way down to Alder Creek along the American River. The Natoma Company then set about attempting to evict settlers on the property because they were cutting down trees and selling the wood. The ejectment suit set off a fire storm of protest and unsubstantiated allegations by the settlers, many of whom were miners, against the Natoma Company.

What should be noted is that Folsom never went after the miners for rents. The Natoma Water and Mining Company, never went after the miners on their property for rents either. Mining was an untouchable occupation. The one exception were the Chinese miners who were robbed and taxed at will. However, Catlin, having been accused of favoring the Chinese miners for water sales, repudiated the accusation in his letter to the Sacramento Daily Union.

“The general feeling of the miners towards the Company, even at this time, is one of good will and satisfaction. The few malicious and evil disposed persons who have fanned into a flame a feeling of ill-will, which often prevails against the Chinese, until it culminated to the bursting point at Alder Creek, will be disappointed. It will not avail them anything in the injunction suit. Many of those who violated the law for the purpose of vindicating imaginary wrongs, have already opened their eyes, and begin to see that they have been used by designing persons to accomplish objects in which they have and feel no interest. These parties have kept up a brisk fire through the press, and no doubt have succeeded to some extent in their design of creating a prejudice in the minds of the community against the Ditch Company. The most studied and ingenious misrepresentations have been made, with a view of creating sympathy for those who had no sympathy for the inoffensive Chinese on Thursday or Friday last; the most exaggerated statements have been made respecting the numbers engaged in expelling the Chinese, the objects of the Company, the preference of the Company for the Chinese, and the feelings of the miners generally. The Ditch Company, which has always pursued an undeviating course of impartiality to all its customers, has been denounced as a ” monopoly,” a “soulless corporation,” and sundry other hard names, by insane scribblers and idle Ishmaelites, the pests of every neighborhood. Nothing short of a sense of duty to those whose private interests are in some measure in my keeping, as President of the Natoma Company, could have induced me to notice in a public manner these efforts to injure the stockholders of said Company. A. P. Catlin”

Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 14, Number 2169, 10 March 1858

Before the Leidesdorff land grant map could become officially recognized, it had to meet the approval of the U. S. Government. In September 1858, even though the Commissioner of the Land Office at Washington found the original surveyed map in order for a land patent, Secretary of the Interior Jacob Thompson, under President James Buchanan, disapproved it. Thompson sent the matter back to California to be resurveyed. The reports were that Secretary Thompson thought the boundary ran too far to the east. This is the same conclusion that opponents of the original survey made.

A second survey was undertaken and the subsequent map was known as the Mandeville survey. The new Mandeville survey held to Thompson’s instructions that the lomerias were to begin at Alder Creek, some two miles to the west of the original survey. The Mandeville survey was completed in 1859 and then opened for examination by interested parties to file exceptions. In the midst of all the new surveys and examination, Congress passed legislation in 1860 that gave new powers to District Courts in California and the authority to order any survey into court and decide on it.

In November 1861, the District Court tossed aside the new Mandeville survey and decreed the original Hays survey valid. The United States District Attorney then appealed the decision and it landed on the steps of the U. S. Supreme Court in the form of United States vs. Halleck, et. al. As civil war was about to erupt, California Governor Downey appointed Captain Halleck to be the Major General of the Second Division of the California Militia. Halleck would go on to be general-in-chief of the Union Army under President Lincoln during the Civil War.

Catlin Argues Before the U. S. Supreme Court

Amos Catlin, President of the Natoma Water and Mining Company, was a lawyer by training. In between running the Natoma Company, being elected to the California Senate in 1852 and Assembly in 1857, Catlin also practiced law. It is unclear whether he was recruited or volunteered to represent Halleck and the Folsom estate before the U. S. Supreme Court. He most likely felt compelled to defend the original survey since the Natoma Company had purchased so much acreage from the Folsom Estate. Either way, he took up the challenge and left for Washington D. C. in November 1863 with his wife.

Catin argued before the U. S. Supreme Court in December of 1863. The Court handed down their decision, in Catlin’s favor, in May 1864. His basic argument revolved around geometry; the western boundary line was two leagues in length. In order to create an area of eight square leagues, the southern boundary line, following a general parallel to the American River, had to have a length beyond Alder Creek, and encompass the town of Folsom. Whereas lawyers will often cite prior legal cases, quote code, and philosophize on the law, Catlin’s published comments in the opinion are quite matter-of-fact.

“After first directing the starting-point to be the oak tree, and the first line to run from thence “south” two leagues, it says, “thence ‘easterly,’ by lines parallel with the general direction of the said American River, and at the distance, as near as may be, of two leagues therefrom.”

UNITED STATES V. HALLECK ET AL.

“We understand the word easterly in its usual acceptation to mean to the east generally, in contradistinction to west, north, or south, and is correctly applied to any general direction to the east, as opposed to the west, which would not be better indicated by using the terms northerly or southerly. In this decree the term easterly has qualifying words attached to it, showing that it meant the direction of the American River from the oak tree.”

UNITED STATES V. HALLECK ET AL.

In the final opinion, written by Justice Field, the court agreed with Catlin.

“The decree in this case is plain, and admits of only one construction; the object of the appellants is to change the meaning of its language, by showing that the commissioners were ignorant of the true course and direction of the American River, and therefore intended different lines from those they specifically declared, and that they could not have intended the eastern line to run as directed, in disregard of what is asserted to be the true position of the “lomerias.”

UNITED STATES V. HALLECK ET AL.

Catlin returned to California in June 1864. One of his rewards for successfully representing the original Hays survey was being the exclusive land agent for the sale of the remainder of the Rancho Rio de los Americanos under the firm Bowie and Catlin. Three years later, Catlin had negotiated the sale of almost all of the land to settlers, miners, and of course, the Natoma Water and Mining Company.

While back east, Catlin had time to visit the battle field at Gettysburg. He picked up some relics and souvenirs from the battle field that included shot, shells, and a branch that had been perforated with a dozen bullets. He displayed these Civil War relics at meetings of the California Pioneer’s Association in Sacramento and San Francisco. Catlin would move his family from Folsom to Sacramento in the 1860s to practice law full time.

It was a real boost to Catlin’s legal career to have successfully argued before the U. S. Supreme Court. There was a time in 1851, after he had vacated Sacramento due to a cholera outbreak, when he was unsure of his future in California. The Leidesdorff land grant litigation was not the most complicated or intellectually challenging case Catlin would handle. But if arguing before the Supreme Court and winning set a bar of high expectations for Catlin as a lawyer, he would meet and exceed those expectations in the decades to come.

This post is part of a continuing series involving Amos P. Catlin. This historical information will become part of a book on Catlin’s life I hope to publish early 2021. Amos P. Catlin webpage – Kevin Knauss