Before he was for the map of the Rio de Los Americanos Mexican land grant, Amos Catlin opposed Captain Joseph L. Folsom’s expansive view of the vast property in Sacramento County. Catlin’s flip-flop from opponent to proponent of the land granted to William A. Leidesdorff in 1844 by the Mexican government characterized the many twists and turns the litigation took between 1855 and 1864.

Multiple Maps of the Leidesdorff Rancho Rio de Los Americanos

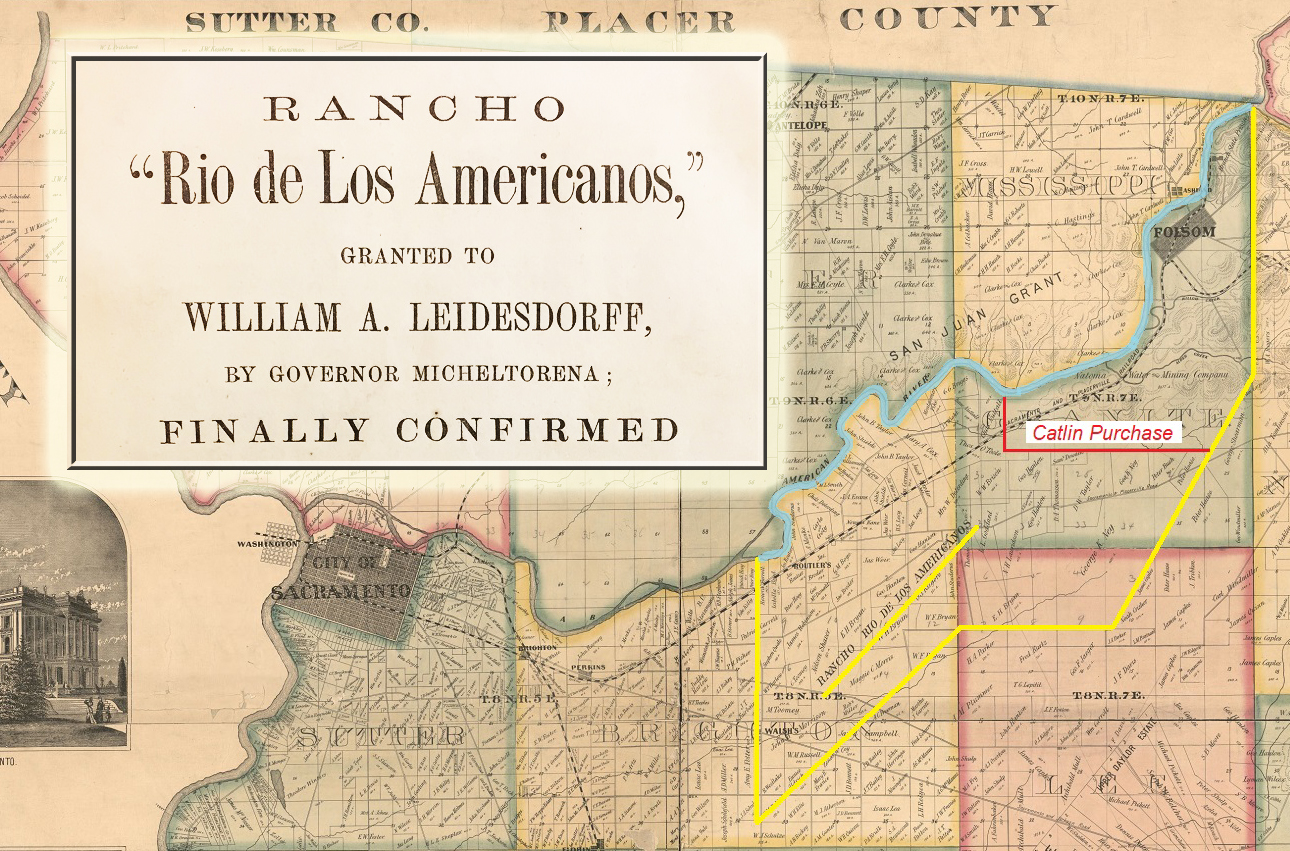

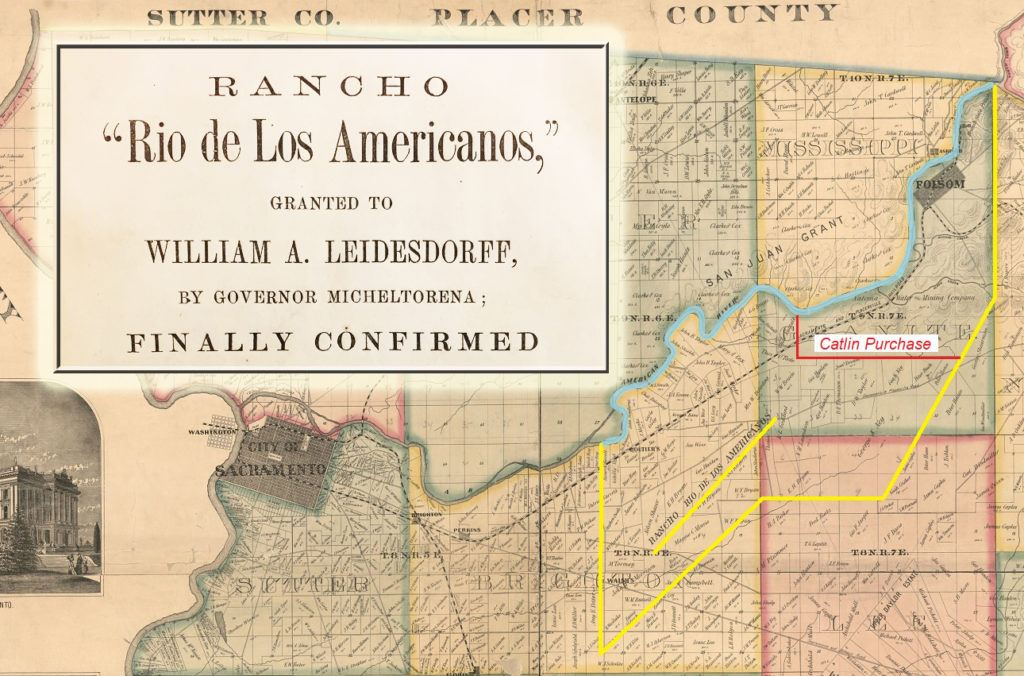

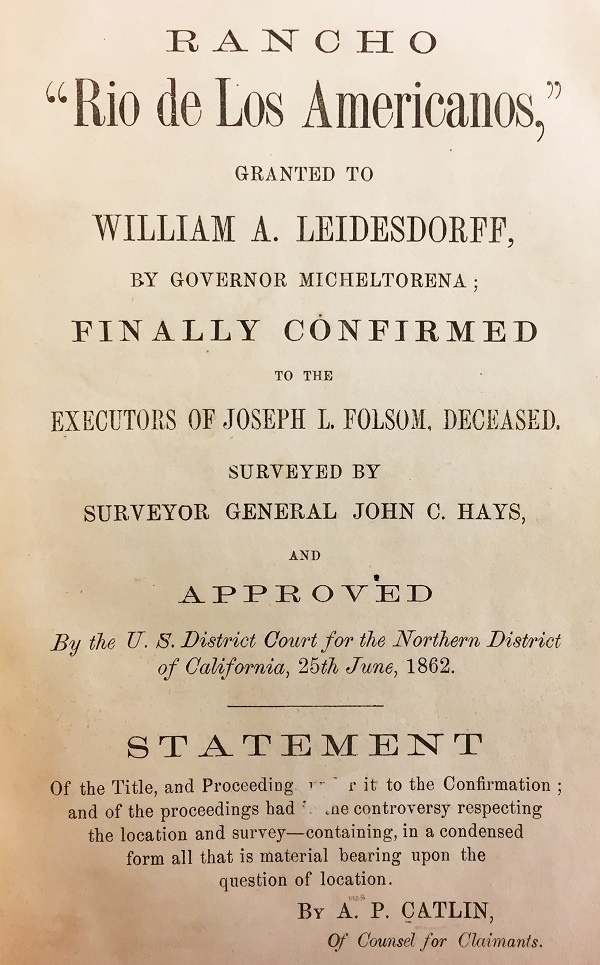

The history of the litigation surrounding the Mexican land grant in Sacramento County is found in the little book with the long titled, Rancho “Rio de Los Americanos,” Granted to William A. Leidesdorff, by Governor Micheltorena; Finally Confirmed to the Executors of Joseph L. Folsom, Deceased, Surveyed by Surveyor General John C. Hays, and approved by the U.S. District Court for the Norther District of California, 25th June, 1862.[1] The case history, compiled by Amos P. Catlin, appears to have been printed in preparation of Catlin’s oral arguments before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1863.

The central point that precipitated numerous legal challenges to the land grant were the boundaries and numerous maps made delineating the borders. In the course of his involvement with the land grant litigation, Catlin would acquiesce to the boundaries established by the Board of Land Commissioners in 1856 and outlined in the Hays survey map. However, before the Rio de Los Americanos land grant was intently studied by commissioners and judges, the general property outlines were known to early Californians.

In 1843, John Bidwell rode over the potential grant property with John Sinclair. The two men were examining the property for Nathan Spear who was considering petitioning the Mexican government for a land grant.[2] William Alexander Leidesdorff would petition for the property and in 1844 was awarded a land grant named the Rancho Rio de Los Americanos by the Mexican government. John A. Sutter subsequently rode over the property with Leidesdorff and would give him juridical possession of the property 4 leagues in width east to west, 2 leagues in length to the south, encompassing 8 leagues of land.[3]

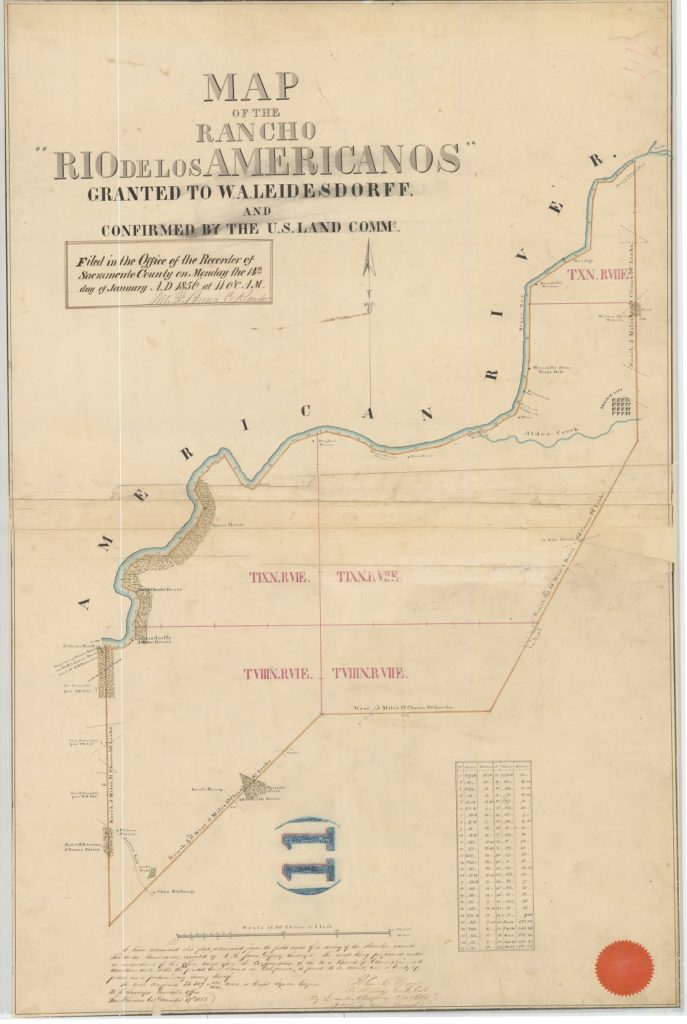

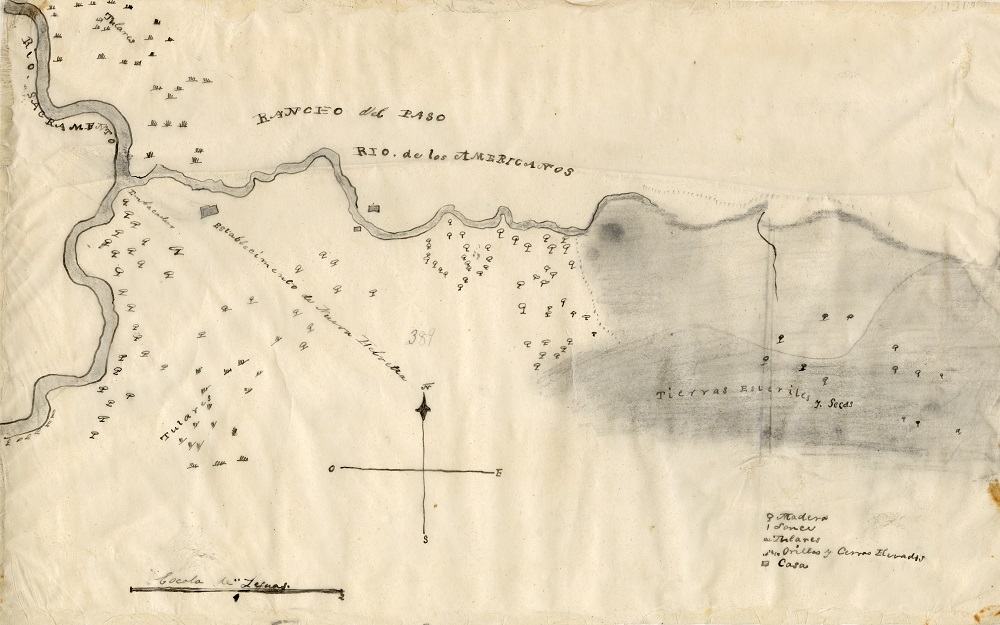

Several maps were made of the land grant. John Bidwell made a map of the property in 1846. There were also preliminary maps made by Colby and one by Goddard.[4] All the maps were slightly different with respect to the eastern boundary of the land grant. The original grant, which Catlin includes in the book in its original Spanish, stated the eastern boundary were the lomerias or low foothills.[5]

Shortly after California became a state, the Board of Land Commissioners was established to review and authenticate Spanish and Mexican land grants. The Land Commission also set the official boundaries of the land grants based the description included in the original grant, along with maps. One of the maps submitted to the Land Commission was drawn by John Sinclair.

When the Rio de Los Americanos land grant came before the Land Commissioners, Catlin argued the Sinclair map was inaccurate. First, it was made by an inexperienced map maker. Second, Sinclair ran out of paper on the right-hand side forcing him to misrepresent Alder Creek and the lomerias.[6] Finally, the map was not to scale. The Sinclair map indicated an eastern boundary further east than was intended by the original grant.

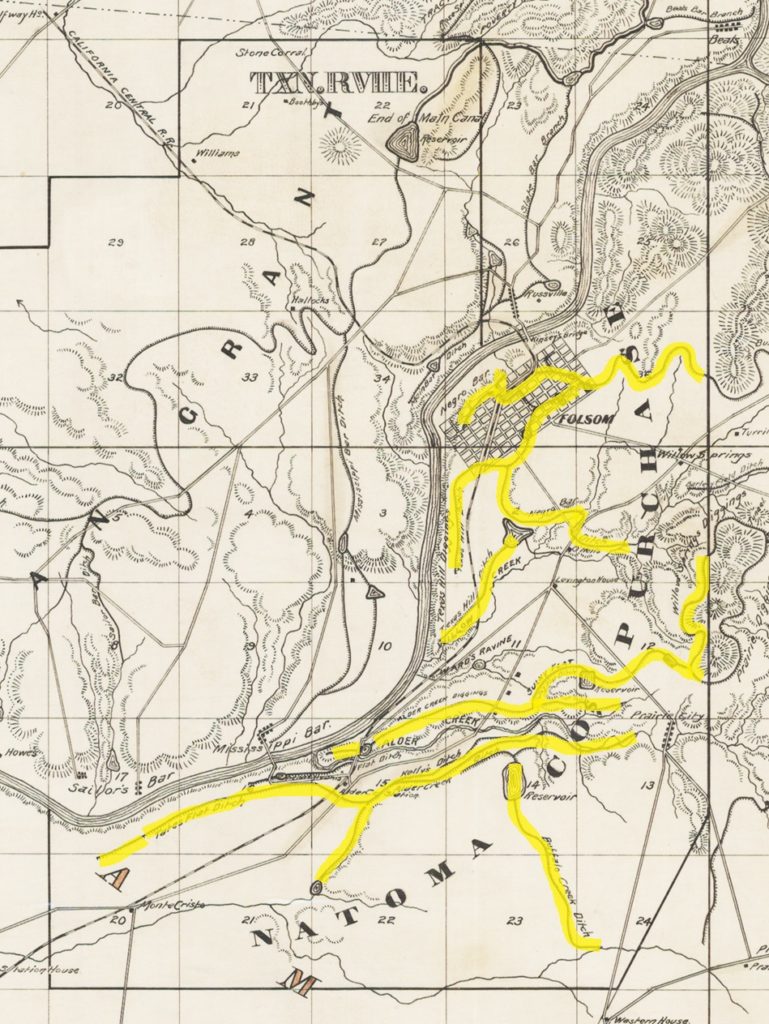

Catlin was representing claimants to land that was potentially encompassed by the land grant. He was also the president of the Natoma Water and Mining Company that had water canals meandering around the foothills from El Dorado County into northeast Sacramento County, in and around the future site of the town of Folsom. It was to Catlin’s advantage to have the eastern boundary of the land grant as far west as possible. The ideal situation was to have the eastern boundary of the grant be established at Alder Creek. Willard Buzzle, a tenant on the land grant, stated he ran cattle north of Alder Creek as he was informed the property extended several miles north of Alder Creek.[7]

Leidesdorff died in 1848 and Captain Joseph L. Folsom was able to gain control of the Rio de Los Americanos land grant. Folsom had a map made in 1850 that showed the eastern boundary intersecting the American River at Negro Bar. Folsom then submitted his land grant claim to the Board of Land Commissioners in September 1852.[8]

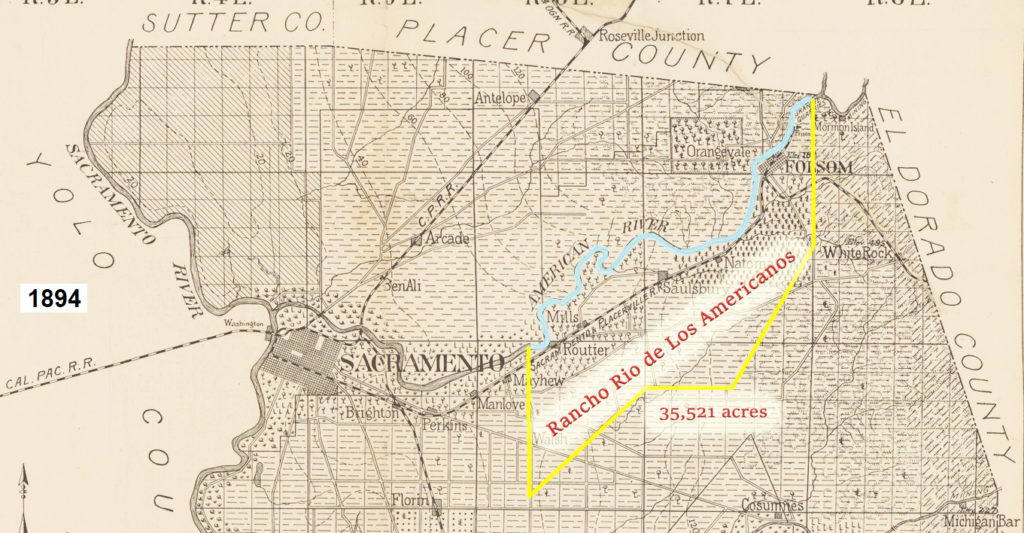

By June 1855, the Land Commission had determined the grant was valid and that Folsom had legal title to the Rio de Los Americanos land grant.[9] In December of 1855 the Land Commission had set the boundaries of the land grant. They gave priority to the description that the American River was the northern boundary and the southern boundary would in some manner mirror the course of the river. The next consideration was ensuring the property included 8 square leagues of land. When the first two conditions were met, coupled with the fixed western boundary being that of the Sutter land grant, the eastern boundary was set 2.5 miles east of where Alder Creek entered the American River. The eastern boundary also corresponded loosely to where the low foothills or lomerias began and were noted in the original grant description.

Hays Survey of Mexican Land Grant Confirmed

On February 18, 1856, Joseph Folsom died and the law firm of Halleck, Peachy & Van Winkle became the executors of the Folsom estate. Catlin and fellow attorney Benham would appear before the Land Commission and dispute the boundaries of the land grant in 1856. Finally, in February 1857, the Land Commissioners made their decree of the land grant and ordered the plat made by Surveyor General John C. Hays entered as the official map of the Rancho Rio de Los Americanos.[10] The U.S. Attorney General dismissed any further appeals to the land grant in April 1857.

In 1856, the Probate Court handling the Folsom estate allowed the executors to sell lots in the new town of Folsom. Catlin would buy several blocks in Folsom in 1856 and 1857. With the land grant boundaries set, it was apparent that Catlin’s Natoma Water and Mining Company’s water canals were trespassing across the land grant. In March 1858, Catlin purchased 9,643 acres of the Rio de Los Americanos for $36,800. The property was in the northeast corner of the land grant and excluded the town of Folsom and the Sacramento Valley Railroad.

Mandeville Survey Ordered of the Rancho Rio de Los Americanos

Then, in September 1858, Secretary of the Interior, Jacob Thompson, rejected the boundaries of the land grant and ordered a new survey.[11] Catlin, who had opposed the Hays survey, now, because of his large investment in the land grant, became one of the biggest defenders of the Board of Land Commissioners determination of land grant’s boundaries. Catlin was particularly irritated by the fact that secret ex parte affidavits were submitted to the Secretary of the Interior with no notice to claimants and purchasers of land within the land grant.[12]

A new round of litigation was underway opposing the new Mandeville survey ordered by the Secretary of the Interior.[13] The U.S. District Court ordered the new Mandeville survey to be presented in court in January 1860.[14] In 1860, congress passed an act that gave more authority to U.S. District Court Judges to review and rule on land grant disputes brought before the court. The Act of 1860 changed the dynamics of the litigation. Even attorneys for the federal government argued against the Mandeville survey in late 1860.[15]

Judge Hoffman Orders 3rd Map Created

After reviewing all of the arguments against both the Hays’ and Mandeville surveys, U.S. District Court Judge Ogden Hoffman ruled that the Hays’ survey was correct and the Mandeville survey was erroneous. But Judge Hoffman did not reinstate the Hays survey boundaries, he ordered a new survey to be drawn based on making the boundaries conform more to a rectangular shape versus a parallelogram.[16]

In January 1862, Catlin and Aug. R. Thompson, a former Land Commissioner Board member, filed a request to have Judge Hoffman’s order of a new survey set aside and petitioned for a new hearing. In the petition for a new hearing, Catlin enumerated 13 points where both the judge and the federal government had erred. One of the issues with the Mandeville survey boundaries and the Judge Hoffman’s order for a new survey was the fact that people had bought property from the Folsom executors and public land outside of the land grant. New boundaries would make some grant land become public land and some public land to the south would fall within the boundaries of the land grant. Judge Hoffman had dismissed the arguments of injury to current land purchases as regrettable.[17]

Catlin refused to concede that property purchased either within or outside of the land grant had no bearing on whether the Hays survey should be reinstated or new boundaries drawn.[18] As Catlin cites, the property sales were authorized under a District Probate Court. The California Supreme Court had also issued a ruling based on a contested eviction order from property bought from the Folsom executors. The Natoma Water and Mining Company had ejected some men from the property bought in the Rio de Los Americanos land grant.

After being convicted of trespassing, the men appealed on the grounds that the Natoma Company did not have proper title to the property because the boundaries of the land grant were in dispute.[19] The California Supreme Court rejected the appellants arguments and stated, “The validity of the grant is, therefore, the law of that case. It can never be questioned again by the Government, or by individuals claiming under the Government, either collaterally in an action of ejectment, or directly in any other proceeding. It is a closed question for all time.”[20]

In his petition to the Court, Catlin supported and praised the logic of the Board of Land Commissioners in setting the land grant boundaries that he was initially opposed to. The land commissioners exhibited sound logic in allowing the northern boundary of the land grant to follow the river, a length greater than 4 leagues. However, by adjusting the southern boundary to parallel major changes in the direction of the American River, the Land Commissioners were able to keep the southern width of the land grant to approximately 2 leagues. They also honored the slightly undefined lomerias or low foothills as the eastern boundary for the land grant.

Judge Hoffman Reverses Order, Reinstates Hays Survey

Judge Hoffman, after having digested all of Catlin and Thompson’s arguments, reversed course. The Judge admitted that, if this had been a new question before the Court, he would advise to make the land grant conform more to a rectangle.[21] On August 1862, Judge Hoffman ordered that the Hays survey with the official measurements and angles, comprising 35,521 acres in Sacramento County, be entered into the record as the official boundaries of the Rio de Los Americanos land grant.[22] The ruling was the end of Catlin’s statement on the history of the litigation, but there would be another chapter in the saga.

The U.S. District Court Judge’s ruling would be appealed and ultimately end up before the U.S. Supreme Court. Catlin would travel to Washington D.C. in 1863 to assert that the Hays survey was the correct delineation of the Rio de Los Americanos land grant. Just as Judge Hoffman was influenced by Catlin’s arguments, so were the Supreme Court Justices. The Supreme Court affirmed Judge Hoffman’s ruling in 1864. Finally, the litigation over the Rancho Rio de Los Americanos had concluded.

[1] Rancho “Rio de Los Americanos,” Granted to William A. Leidesdorff, by Governor Micheltorena; Finally Confirmed to the Executors of Joseph L. Folsom, Deceased, Surveyed by Surveyor General John C. Hays, and approved by the U.S. District Court for the Norther District of California, 25th June, 1862. San Francisco, 1862, B.F. Sterrett. Huntington Library, Call Number 1095, Catlin, Amos P. collection

[2] Page 23

[3] Page 23

[4] Page 27

[5] Page 2 and 6

[6] Page 28

[7] Page 24

[8] Page 7

[9] Page 8

[10] Page 11

[11] Page 12

[12] Page 11

[13] Page 12 and 13

[14] Page 13

[15] Page 19

[16] Page 36

[17] Page 35

[18] Page 37

[19] Page 47, Natoma Water and Mining Company vs. Clarkin et al., 14 Cal. Rep., pages 550-51

[20] Page 51

[21] Page 64

[22] Page 65