Before Auburn, California, became associated with the historic construction of the Transcontinental Railroad, there was another railroad line that brought Auburn into existence, then broke the town. It would be twenty years after the city of Auburn was dissolved in 1868 before it would cut a deal with an enterprising Sacramento attorney to pay off old railroad bond indebtedness so the residents of Auburn could incorporate once again.

In 1856, the Sacramento Valley Railroad (SVRR) steamed into Folsom demonstrating that a railroad could be built and operated in California. Theodore Judah, who laid out the SVRR, had plotted a route that would take the train over the American River at Negro Bar and up to Marysville. He even explored easterly routes from the main line up to Auburn, but none of these roads would be attempted.

Placer and Nevada Counties Want A Railroad Line

Gold mining had moved from the placer mines in the river bed into more arduous undertakings with hard rock mine shafts and the hydraulic mining. These new gold extraction sites were in the foothills and mountains with increasingly difficult freight routes for wagons pulled by animals. A railroad into these communities seemed like the best fit to support the fledgling mining communities in Placer and Nevada counties.

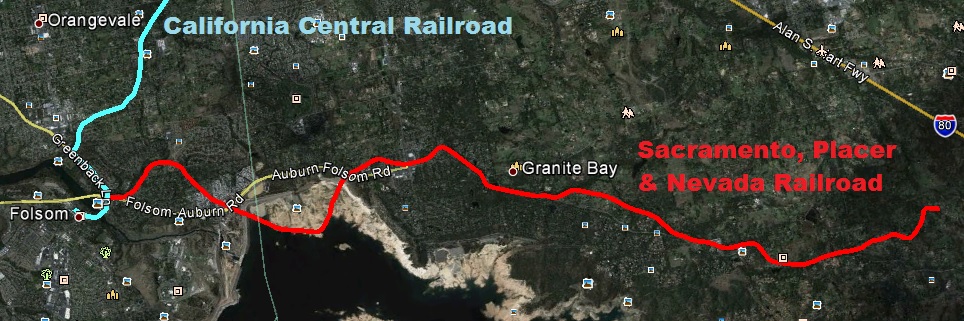

Railroads were expensive ventures and the SVRR was heavily in debt when progress stopped at Folsom. Charles Lincoln Wilson, one of the original founders of the SVRR, organized a new company, the California Central Railroad, to finish the route of the SVRR up to Marysville. A variety of different routes were considered to connect Auburn to the new California Central Railroad (CCRR). A road surveyed by engineer Sherman Day from a point north of Folsom up to Auburn showed the most promise in terms of construction costs.

In early 1860 with the CCRR pushing toward Lincoln, the foothill newspapers were advocating for an extension up to Auburn and Nevada City. The Placer Herald was forecasting, “The road will be built to Auburn. Capitalists have already given assurance. The advantages of the route are, in brief: the distance is less, the grade far easier, and the value of the road when once constructed, more, requiring less expense and being more effective in the transportation of upward freight.” – Placer Herald, Volume 8, Number 19, 14 January 1860

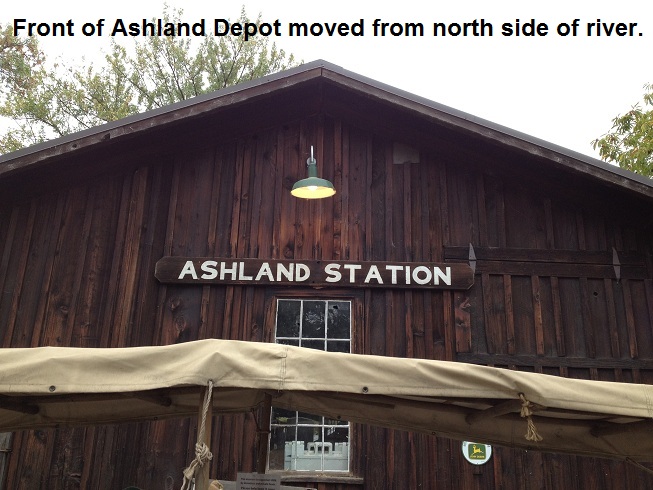

To investigate all the possible routes, the Sacramento, Placer, and Nevada Railroad Company was formed in 1859. The board then commissioned Sherman Day in October of 1859 to survey all the routes possible. In Day’s estimate, the route from Folsom to Auburn was the best and it would only cost $1,000,713 to construct. The lower division, the first 14.5 miles beginning at Ashland, was the least expensive to build at $376,133. Because of the lower expense and interconnection with the SVRR and CCRR, Day advocated starting the lower division first.

Day also included estimated revenue projections for the full length of the road from Folsom to Nevada City. However, instead of beginning with a profit or return on investment projection, he offers a rhetorical question, “Does it pay to do without the road? Does it pay the people of Placer and Nevada counties to travel in stage coaches and mud wagons, or even in baggies covered with dust in summer, and with mud in winter starting at unreasonable hours and paying $8 or $9 from Nevada and $4 from Auburn to Folsom?”

After engineer Day’s emotional comfort argument for the railroad, he summarizes some rosy revenue projections resulting in an annual net income of $176,195. This dollar figure, he concludes, yields a return on investment of between 17 to 19 percent. Regardless of the questionable economic analysis of the railroad, the promoters of the road understood they would need government help to capitalize the project.

Auburn Incorporates, 1860

On March 31, 1860, the day that the Placer Herald published Day’s full report on the SPNRR, they also reported that an Act to incorporate the town of Auburn had been passed by the legislature. The incorporation of Auburn was important because only chartered municipalities could issue bonds for the construction of projects. It also should have been evident that certain parties had already mapped out a route for financing the railroad before it was even proposed. Day had liberally sprinkled in references to the Placer Herald newspaper offices, one of the road’s main proponents, in his report on the SPNRR.

Faster than a speeding locomotive, the town of Auburn was rushing to incorporation. April 11, 1860 was the date set for voting on incorporation for residents within the established boundaries. If the outcome was favorable, April 18th was the date to elect town trustees. On April 18th, not only were the new trustees elected, it was reported that the California legislature passed a bill allowing the new town of Auburn to place before the electorate a measure to take $50,000 in stock in the SPNRR. Later in the month, the legislature passed a bill allowing Placer County to subscribe to stock in the SPNRR as well.

June 4th was set by the Auburn trustees for a special election to invest $50,000 in the SPNRR. After the votes were counted, there was not a single vote in opposition to the Auburn’s investment in the new railroad venture. While Auburn voters were enthusiastic about investing in the new railroad, the rest of Placer County was not. A majority of Placer County voters voted against a proposal to invest $125,000 in the SPNRR. Most of the county residents could see no benefit from the railroad for them except higher property taxes.

By 1859 Theodore Judah was already advocating for a Pacific or Transcontinental Railroad. It was common knowledge that Judah was surveying a route almost the length of Placer County, west to east. Whereas the SPNRR was planned to traverse Placer County south to north, leaving large portions of the east and west of the county with no service. The negative vote of Placer County did not halt progress on the SPNRR. With the Auburn investment, along with other subscribers of the stock, the railroad began to be built.

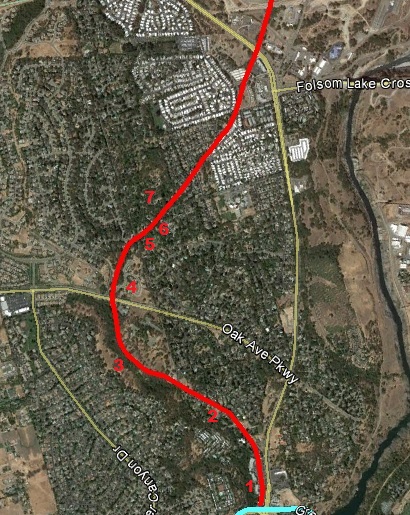

John P. Robinson was appointed Chief Engineer of the SPNRR in May of 1861. He was also the Chief Engineer of the SVRR. The grading of the line commenced in August of 1861 with the line beginning at Big Gulch, soon to be known as Ashland. This was the point at which the CCRR had constructed a wooden trestle bridge over the American River. From what would become the Ashland Depot, the SPNRR line went up today’s Hinkle Creek and then paralleled the North Fork Ditch water canal.

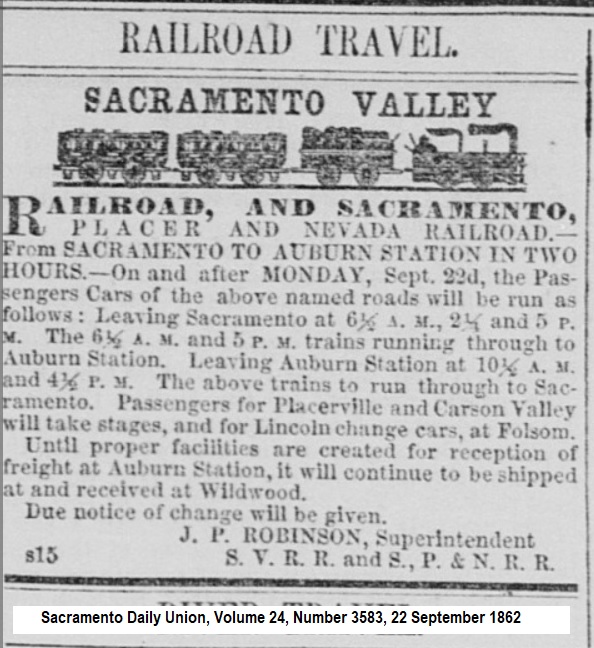

At the small community of Rose Springs, the railroad followed a branch of the North Fork Ditch called the Allen Ditch up to Miner’s Ravine creek. The line would weave back and forth over today’s Auburn-Folsom Road to a point north of King Road. By September 1862, the SPNRR was advertising service from Folsom to Wildwood Station.

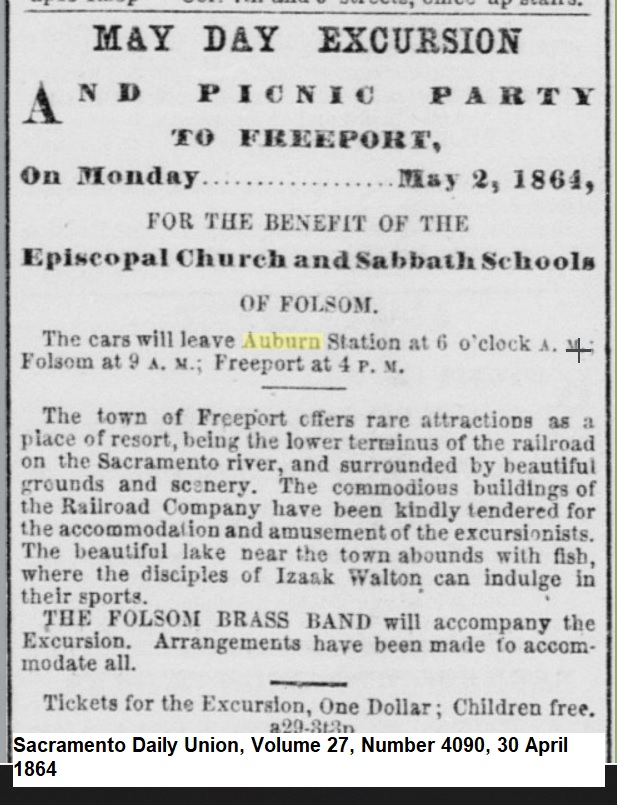

Auburn Station would be the end of the line both figuratively and literally for the SPNRR. Reports at the time indicate that freight was moving its way down the wagon road from Auburn to the terminus. A granite quarry also invested in extending a rail spur to its quarry operations. The Alabaster Cave in El Dorado County, across from Rattlesnake Bar, was becoming a tourist attraction and the railroad helped deliver visitors not far from the destination. This had to have pleased J. R. Gwynn, owner of the Alabaster Cave and one of the original Auburn town trustees.

With construction of the SPNRR stalled south of Newcastle, the freight and passenger revenue was not generating enough money to pay dividends to the stock holders. One of the stock holders was the town of Auburn. The bonds Auburn had issued to fund their investment in the SPNRR stipulated interest payments of 8 percent payable semi-annually to the people they sold the bonds to. The full face value of the bond, usually sold in $250 increments, was payable after twenty years of issuance.

Also included in the Auburn railroad bond act was a property tax trigger. If the railroad was not generating enough revenue into the town finances to pay the interest on the bonds, the city was to levy a property tax sufficient to collect the funds to pay the bond interest. In March 1863 the Auburn trustees had to trigger the property tax option and levy a tax of $2.10 per hundred dollars of assessed property value on Auburn residents. If this local property tax was not enough, Placer County had voted to invest in the Central Pacific Railroad, then building the Transcontinental Railroad, which would necessitate more railroad property taxes on Auburn residents.

By early 1864, the Central Pacific Railroad was making daily progress to reach Auburn from its starting point of Sacramento. Lester L. Robinson was one of the contractors of the Sacramento Valley Railroad (SVRR). When the SVRR failed to pay him, he was able to engineer a takeover of the company. While Lester Robinson initially supported the SPNRR, he was now focused on building a railroad over the Sierras to compete with the CPRR.

As an investor in the SPNRR, Lester Robinson moved to foreclose on the railroad in May 1864. In the initial law suit (Robinson, et al vs. Sacramento, Placer and Nevada Railroad) the town of Auburn trustees filed a petition to intervene, but it was not successful. The SPNRR board of trustees did not put up a fight against Robinson’s foreclosure. In June of 1864 the SPNRR was put up for sale and purchased by John P. Robinson of the SVRR. The purpose of the purchase was to take up the rails and move them down to Folsom so Lester Robinson and the Placerville and Sacramento Railroad could continue their alternate road over the Sierras.

It was widely known that Lester Robinson planned to abandon the SPNRR and use the rails on the Placerville and Sacramento Railroad line. This left the town of Auburn with a $50,000 debt in which they had to make interest payments of 8% to bond holders. As the day neared that the railroad would begin to be dismantled, Griffith, who owned a granite quarry and had invested heavily in the SPNRR, filed an injunction to stop John P. Robinson from removing the tracks. The injunction was granted pending further review. However, that did not stop the plan to rip up the tracks.

Auburn Railroad War Begins

In early July, John Robinson hired men from San Francisco to come up to Folsom to start the dismantling of the SPNRR. With the removal of the rails, Placer County Sheriff Sexton was called out to halt the action. Sheriff Sexton arrested approximately 12 of the men who were later released on bail. The dismantling party then moved to the cover of darkness to proceed with the rail rip-up at night. Under Sheriff Poole and Deputy Pittenger were then dispatch to stop the removal but the dismantling party, numbering in excess of 60, repelled the law enforcement officers directions and sent them back up to Auburn.

The fight over the SPNRR was now turning into a railroad war. On the 4th of July, a patriotic posse of citizens, led by Sheriff Deputies, forced the dismantling party to retreat leaving behind one of the rail cars. However, in all the confusion, the dismantling party raiders were able to capture Deputy Sheriff James Sexton, brother of Sheriff Sexton. James Sexton was finally freed and two of the kidnapping conspirators were arrested. The Sacramento Daily Union called for the military to get involved and use the necessary force of powder, shot, and shrapnel on the offending barbarians.

At this point, there was somewhat of a stalemate. Each side had a line of men at the site carefully watching each other. The Sheriff had a posse of five or six men to guard the rails from further molestation. With no warning, the posse of citizens were served with warrants from the Justice of the Peace in Lincoln charging them with disturbing the peace and carrying concealed weapons. As the posse was rounded up to be escorted down to Lincoln, Deputy Coburn was able to secure a horse and ride to Auburn to inform Sheriff Sexton.

It is unknown who filed the complaint in Lincoln against the citizen posse standing guard over the railroad tracks. Regardless, the battle of the rails would intensify. Sheriff Sexton was able to get a contingent of the Auburn Grays, a local Union militia, to accompany him and others down to the site of the track removal. The resulting encounter was more of a brawl than a military offensive.

One pistol shot was fired that passed through the ear of one of the dismantling party. A Placer County Deputy was being pummeled by the other side until one of the Auburn Grays inserted his bayonet into the side of the aggressor. More men arrived to reinforce the Sheriff’s actions and quell the melee. Sheriff Sexton arrested approximately twenty of the dismantling party, five of whom it was noted were Chinese.

In the background of the railroad war, the injunction to stop the removal of the SPNRR line had found its way to the California Supreme Court. The court ruled against the injunction. When Sheriff Sexton was satisfied the order was legitimate, he called a stop to the prevention of the removal of the rails. Instead of trying to prevent the removal of the track, the game plan shifted to arresting the dismantling crews on charges of inciting a riot.

The Sheriff Deputies, Auburn Grays, and citizen posse revisited the site to arrest the men and another fight ensued. The dismantling crew had a fresh contingent of men working on the track tear up. One of the Auburn Grays was so badly beaten he had to remain in the vicinity for a day until he could be moved up to Auburn for medical attention. The dismantling party were able to repulse the Auburn men and continue with the track removal.

At the last battle, the railroad tracks had been removed to within one mile of the Placer-Sacramento county line. As soon as the dismantling party crossed into Sacramento County, Placer County would have no jurisdiction. With the matter mostly settled, this meant that Sacramento County Sheriff James McClatchy would not have to deal with any railroad war.

John P. Robinson was arrested later in July on a warrant from Placer County for contempt against the injunction. His attorney J. C. Goods traveled to Auburn to defend Robinson and seventy-six other men who were arrested on charges of rioting, resisting arrest, and kidnapping. John P. Robinson was use to rough treatment and good at playing hardball politics. He had numerous encounters with the City of Sacramento over multiple issues concerning the SVRR. There were probably a couple people in Sacramento who broke into a smile at the report of Robinson being arrested.

Auburn Dissolved, 1868

After the battle to save the railroad was lost, Auburn went dormant. The town’s pride and pocket book had taken a severe beating. The only way to get out from underneath the $50,000 bond obligation was to dissolve the city. In 1868, Assembly bill 760, An Act to repeal an Act to incorporate the town of Auburn, was passed by both houses of the legislature.

Amos P. Catlin, a young New York lawyer, was bitten by the bug for adventure in 1849 and travelled out to California. He settled at Mormon Island where he pursued gold mining. In 1852 he started organizing the Natoma Water and Mining Company that would go on to build an important water ditch from Salmon Falls down into Folsom and Sacramento County. At one time in the 1850s he was director on the board of the Sacramento Valley Railroad and also the California Central Railroad.

In 1854 Catlin was elected to the California Senate and introduced legislation to permanently move California’s capitol to Sacramento. Even though he pursued mining, railroads, and politics, at his core Catlin was a lawyer. Eventually Catlin moved to Sacramento and practiced law full time. He successfully litigated some bond cases on behalf the city of Sacramento giving him keen insight into the world of municipal bond debt.

Catlin was a litigator, not so much a deal maker. He successfully represented the Leidesdorff land grant map before the U. S. Supreme Court 1864. There was period of time in the 1860s when Catlin could be found arguing cases before the California Supreme Court on a weekly basis. The city and county of Sacramento would routinely turn to him for counsel on matters relating to charters, contracts, and bond debt.

In 1885 Catlin began representing Thomas Bell of San Francisco in a case filed in federal Circuit Court to redeem the Auburn SPNRR bonds. Thomas was suing for the original amount of the bonds purchased, $44,750, with interest, but never paid by Auburn. The amount was over $140,000. The attorney’s representing the defunct town of Auburn, C. A. Tuttle and E. L. Craig, argued that there was no case because the service summons was not good. In reality, both sides were bluffing to a certain extent.

The speculation was that the real plaintiff was Lester L. Robinson, who was the primary antagonist for the removal of the railroad tracks for the Placerville and Sacramento line in the first place. Robinson’s play to recover $140,000 was diminished by the existent of letter he had written to one of the trustees of Auburn in 1864 offering settle the outstanding bond debt for $7,500, primarily to cover legal expenses resulting from skirmishes surrounding dismantling the tracks.

Since the law suit was on shaky legal ground, Catlin met E. L. Craig to discuss a settlement. There were some differences of opinion and since Auburn had dissolved, the record keeping was not sterling. Not all of the bonds could be accounted for. It was unknown if they were sold or just lost. The twenty-year maturity date of the bonds was rapidly approaching, making time of the essence to secure a settlement. The leverage Catlin had to strike a deal was the eagerness of the Auburn residents to reincorporate as a proper city, the seat of Placer County.

Catlin’s Offer and Compromise

Tuttle and Craig called an Auburn citizens meeting to discuss their options. At the meeting they presented a letter from Catlin that summarized the situation and various settlement options.

October 6, 1887

E. L. Craig, Esq. Dear Sir: The 179 bonds described in the complaint are all the bonds that are known of. I have an impression – just how I obtained it I cannot now call to mind that the full amount of $50,000 was not actually issued.

Neither L. L. Robinson or Mr. Bell know anything of any more. The 179 bonds embrace two or three which were owned by a Mr. Addison, who transferred them to Mr. Bell before the suit was brought, and they were the only ones, as I am Informed, that were disposed of by L. L. R. to others than Bell.

These bonds, if they are outstanding, are beyond peradventure, barred, and do not cut any figure in the matter. An incorporation of the town now would be a new corporation no more connected with the old corporation than it would be with the famous corporation known as the “Contract and Finance Company,” defunct some fifteen years ago.

The plan for raising the money is a thing I have not thought of, it being a matter naturally to be devised by you and your friends. While cash is very desirable in all cases, my idea has been in this that time was necessary and of course must be conceded. I should think an incorporation of the town, or rather a town most necessary and beneficial. The obligations of the new town or city, in the form of bonds or promises having a reasonably long or short time to run, with interest say at six percent would be all we could ask. The $44,750 of bonds with coupons attached in my hands to be surrendered on receipt of the new bonds.

Perhaps another plan might commend itself to those who are taking the enterprise in hand, such as this: say a syndicate (a word of late somewhat common), i. e. a few citizens of fair personal responsibility to give their notes payable at a reasonably early date for the aggregate of $10,000, and lake a transfer of the bonds. They could then proceed more leisurely and with more deliberation with the scheme of a new town or city, and perhaps raise the money without issuing bonds. The new corporation might have authority to pay out of its general fund, raised by general taxation, the money advanced by individuals to take in the bonds, and thus not have the new city start out with a bonded debt, even if it be a small bonded debt. Yours truly, A. P. CATLIN.

A small committee of three was formed, residents Hollenbeck, Stevens, and Crutcher, to further investigate and contemplate the offer. Dr. R. F. Rooney offered an unofficial resolution that Auburn should be incorporated conditionally upon the success of a bond suit settlement. The motion was unanimously carried by the small gathering in attendance.

By early 1888 Auburn residents had formulated a plan and presented it to Catlin. Attorneys Craig and Tuttle reported back to the Auburn citizens committee on the conference they had with Catlin and the agreed upon settlement. Catlin would deposit the $44,750 in bonds in the Placer Bank, plus another $1,000 in SPNRR bonds that had been found. The bank would hold them for six months, during which time the citizens of Auburn were expected to incorporate and redeem the bonds for the amount of $9,350 at six percent interest.

Auburn Reborn, 1888

Craig and Tuttle outlined the process for becoming a city again. They had to have a petition signed by 100 electors requesting that the Placer County Board of Supervisors call an election for the Auburn incorporation. Residents Fulweiler, Lardner, and Tuttle were selected to draft the petition. As agreed to, Catlin deposited the old dusty and musty bonds with Placer Bank in March 1888 and that started the clock ticking toward the new Auburn incorporation effort.

Placer County quickly received the petition for a vote to incorporate, approved it and set an election date of April 24, 1888. The results were 167 for and 62 against incorporation. The next order of business was to clear up the bond debt. The new city of Auburn trustees convened and set a July 2nd election date for the town to vote on the bond settlement agreement. The vote for indebtedness passed 92 to 11. Auburn was reborn and could put the old railroad in its past.

Route of the Sacramento, Placer and Nevada Railroad

Amos P. Catlin, The Whig Who Put Sacramento on the Map

Source material comes from the California Digital Newspaper Collection: Sacramento Daily Union, Placer Herald, and Auburn Journal. Additional information was garnered from the Center for Sacramento History, California State Archives, and California State Railroad Museum. Please contact me if you would specific dates and sources.