Whenever I publish my history research I erase the n-word from any text or map included in the presentation. I recently visited a public historical display and the n-word was displayed on a map within the exhibit. I’ve concluded that in public displays, the n-word should be erased, blanked out, or airbrushed over. There is no need to give any person a modicum amount of any rational to use the word.

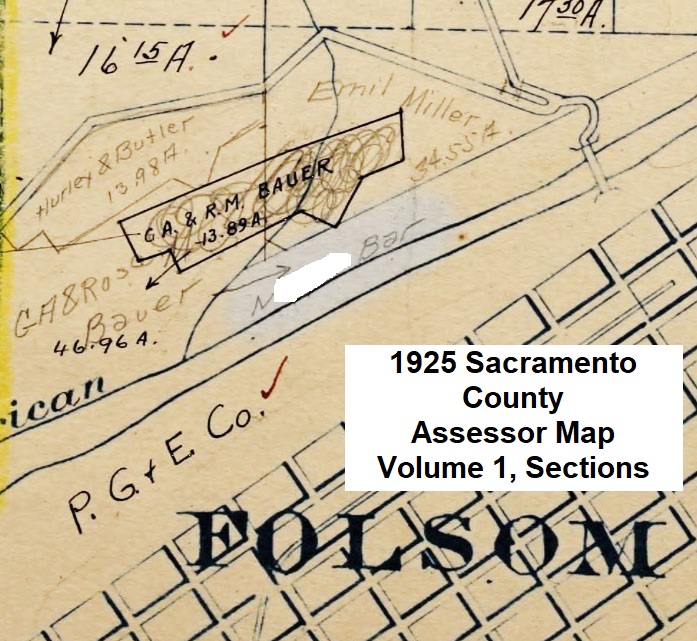

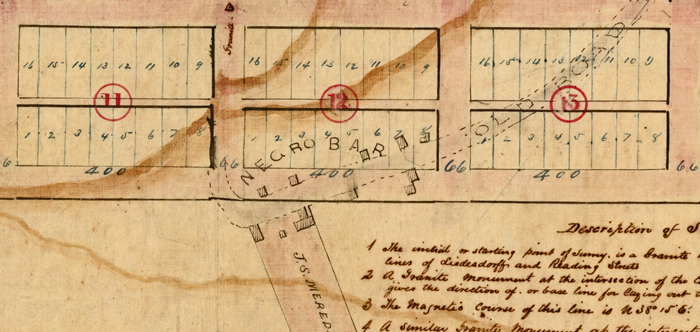

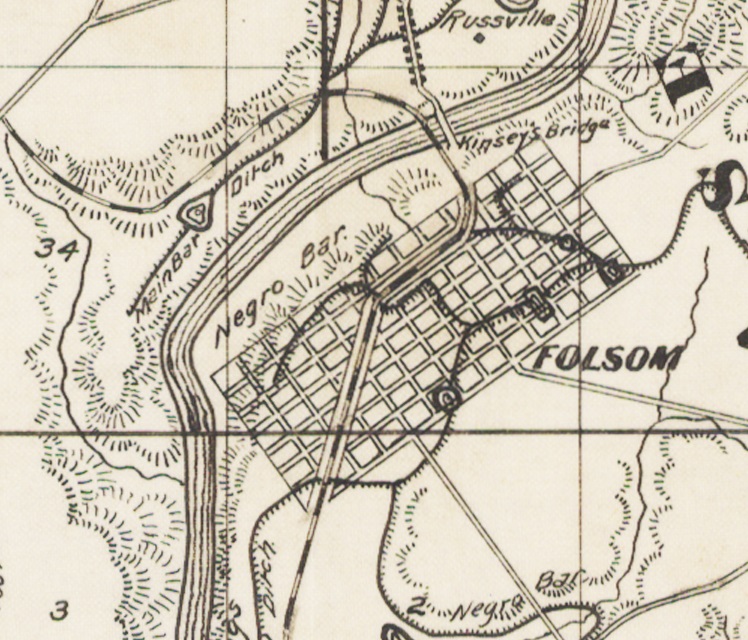

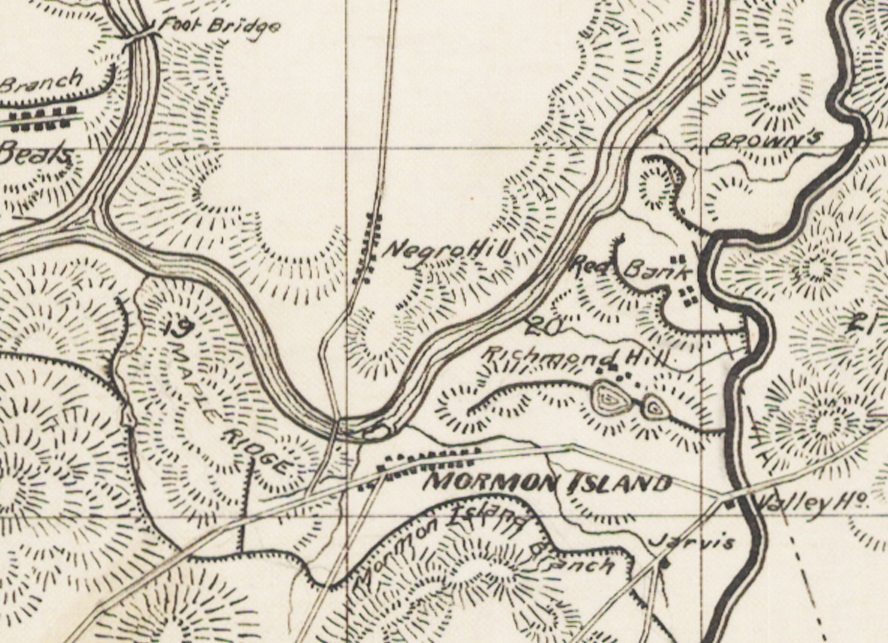

My history research focuses on California’s Gold Rush and the men and families that stayed in California. The most prominent references to Black people in documents and maps from the 19th century for the region I study include Negro Bar and Negro Hill. While there are newspaper references to Black people using the n-word, most correspondence, documents, and maps used the term Negro to reference the location associated with Black individuals.

Initially, I was uncomfortable with the term negro. However, I rationalized that negro refers to the color of the individual and does not project any derogatory assessment of the individuals. Of course, my rationalization is a little naïve because any reference to skin color is usually loaded with negative baggage. The California State Parks has determined to rename Negro Bar – an early Gold Rush mining area on the American River – to the temporary Black Miner’s Bar.

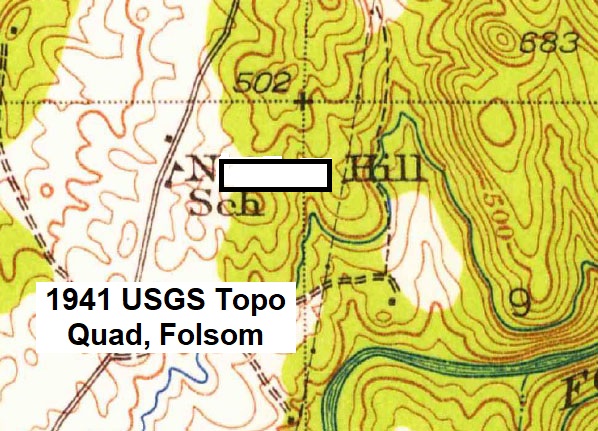

Regardless, the n-word drips with racism, white superiority, and an unfounded animus to any person who is Black. I found it surprising that the n-word began popping up on official government maps and physical structures in the 1940s and 1950s. I can only conclude that federal employees were so comfortable with using the racist n-word to describe Black Americans they took it upon themselves to change the historic place names of Negro Bar and Negro Hill to N- Bar and N-Hill.

When Folsom Dam was being constructing in the 1950s, the Army Corp of Engineers relocated the burials within the footprint of the Folsom Lake to the Mormon Island Relocation Cemetery. For those unknown individuals buried at Negro Hill a concrete grave marker was poured that lists ‘Unknown N- Hill.” In the 2000s, in response to community pressure, the Army Corp of Engineers replaced the grave markers with ones that read “Unknown… Negro Hill.”

There are people who oppose any change to historical references. They argue that erasing certain racist and bigoted references only sugar coats and softens history to create pleasant imagery. I think the applicable term is white-washing history. That is what white men and women in positions of creating the historical narrative the United States have done; they write history that puts white people in a favorable frame of reference.

While I am sensitive to the white-washing of history, via erasing the n-word, there is a place for including racist and bigoted terms. This place is usually in a formal paper or academic setting where the context is discussed and examined. California in 1849 was a very racist and bigoted place. There is a fairly long list of races, ethnicities, and religions that the minority U.S. born white men disliked in California.

A public exhibit viewed by children is not a venue to display racist terms like the n-word. In these exhibits there is no context for the term. The adult or child only sees that the n-word was used on an official government map so it must not be that bad. It is that bad. When the n-word is spray painted on someone’s house, school, or other property, the community is quick to cover over it, erase it.

It was wrong for government employees to use the n-word on official maps. Those people perverted history by inserting their bias against Black men and women. I’m not sure why the public display of the n-word was left in the exhibit that I visited. Perhaps, it was an oversight. I hope it was not a rationalization that the handwritten note of the n-word on the map was somehow historic in nature. While racism is historically significant, as historians we do not have to promote it in a public exhibit.