Hiking along the outline of the historic Negro Hill Ditch at Folsom Lake.

It can be a difficult task to locate the faint outlines of the Negro Hill Ditch which is usually under water at Folsom Lake. But when the lake is low enough it’s possible to find the old grade and structures associated with the historic water canal that ran from east of Salmon Falls down to Negro Hill and Massachusetts Flat. In the autumn of 2016 I was able to complete my goal of walking along most of the Negro Hill Ditch.

Historic Negro Hill Ditch Water Canal

Unlike the Natomas Ditch and the North Fork Ditch, the Negro Hill Ditch was never lined with concrete. The Negro Hill Ditch was the smallest of the three water canals constructed in the 1850s to bring water to the gold miners along the south and north forks of the American River. It was located on the north side of the South Fork of the American River, opposite the Natomas Ditch located on the south side. Both the Natomas and Negro Hill Ditch began at the Natomas Dam on the South Fork of the American River approximately 300 yards downstream from cantilevered Salmon Falls Bridge.

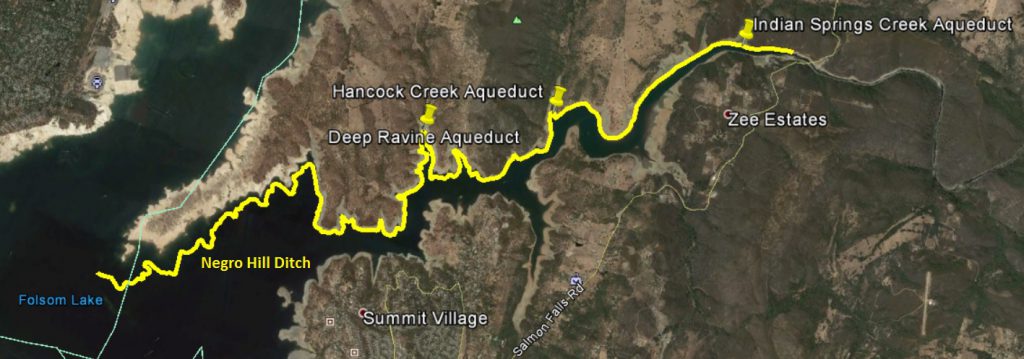

General outline of the Negro Hill Ditch from Salmon Falls Bridge down to the Peninsula in Folsom Lake.

Gold Rush Era Water Ditches along the American River

Whereas the Natomas Ditch and the North Fork Ditch could deliver their water into other areas outside of the river, the Negro Hill Ditch terminated above the confluence of the north and south forks of the American River. While the other ditches could sell their water to other industries and agriculture, the Negro Hill Ditch had a diminishing consumer base as gold mining faded into the history books.

As the name implies, the Negro Hill Ditch was the primary water source for the Negro Hill mining district across from Mormon Island. The ditch started out at an elevation of approximately 450 above elevation and terminated above the confluence at approximately 370 feet of elevation. The overall ditch length was approximately 12 miles. I have yet to uncover the original dimensions of the ditch. But from the remnants that are still visible it had a top width of 5 feet, a depth of 3 to 4 feet, and a base of approximately 3 feet. It does not appear to have been as large as its counterparts the Natomas or North Fork Ditch, but it wasn’t carrying as much water either.

As far as I can tell, the Negro Hill Ditch was primarily earth filled with local rocks usually supporting the river side of the canal. A heavy layer of red clay dirt outlines where the canal bottom would have been. There are no indications that Negro Ditch was ever lined with concrete like the Natomas and North Fork Ditch. Both of the latter ditches had concrete linings installed in the 20th century to reduce loss due to seepage from the porous earth filled lining. It wouldn’t necessarily make economic sense to line the Negro Hill Ditch with concrete if the water sales were declining with no future in sight.

Red clay soil and level grade outline the old Negro Hill Ditch around the hills on the north side of the South Fork of the American River.

The lack of reinforcing concrete, along with the steep hillsides, meant the Negro Hill Ditch retaining wall structure easily dissolved when inundated by water from Folsom Lake. In most places only the red dirt bottom remains as a legacy of the Negro Hill Ditch. The retaining wall rock tumbled down the hillside as the Folsom’s water level rose. Soil and sediment from above the ditch also washed down covering up parts of the ditch, aqueducts, and retaining wall rocks.

Unique stone aqueducts of the Negro Hill Ditch

The areas were concrete is visible are along the 3 aqueducts. I found the aqueducts across an area known as Deep or Big Ravine (Anderson Creek on the 1944 Auburn topographical map), Hancock Creek and Indian Springs Creek. All of these areas would have generated healthy seasonal creek flows into the American River. Creeks full of water rushing downhill were known to washout the canals and flumes.

All of the aqueducts were constructed with local stone. They all seemed to have a lining of concrete within the channel of the aqueduct. This would make sense as the space between the rocks, if only a 1/8th to ¼” width, would allow tremendous amount of ditch water to leak through. Unfortunately, the level of silting from Folsom Lake prevented a thorough inspection of the concrete lining.

Indian Springs Creek Aqueduct

Only the aqueduct across Indian Springs Creek used a concrete mortar in between the square blocks of stone. Additionally, iron railroad rails were used as support to the rock over the creek.

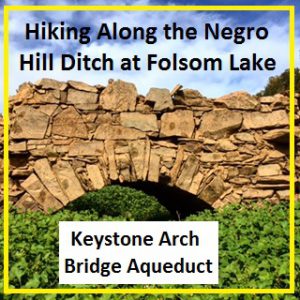

Keystone Arch Aqueduct over Hancock Creek

By far the most interesting of the aqueducts was across Hancock Creek. It was of a keystone arched bridge construction type. A frame, possibly wooden, would have had to have been constructed in order to place stones to create the arch. The base width underneath the arch was at least 10 feet. A picture showing the underneath the arch shows a relatively uniform interior arch of stones. There is no concrete evident. The arch is held together by the friction or compression of the overall structure. There was a layer of concrete within the channel of the aqueduct.

The keystone arch aqueduct is just south of Higgins Point on Hancock Creek. The south facing hillside, across from Higgins Point is virtually vertical. I have no idea how they built the ditch across such a steep cliff. While I could see a narrow path along the solid rock hillside, there was no way I was going to attempt a crossing.

Stone Aqueduct Buried in Folsom Lake Silt

The aqueduct across Deep Ravine is heavily silted from the soil washed down from the surrounding hills. I could not tell if aqueduct had a square or arched construction over the creek. There did not appear to be any concrete mortar in between the visible stones. Concrete was visible on the sides and in the channel of the aqueduct.

If I had to guess, I would say the stone aqueducts along the Negro Hill Ditch were later improvements. It seems most water canal construction favored wooden flumes to cross ravines with potentially high creek flows during the initial construction phase. It’s possible that after repeated wash-outs of the ditch, a stronger aqueduct of stone was constructed. The aqueduct over Indian Springs Creek would not have had easy access to the railroad rails in the early 1850s.

Negro Hill School House Foundation

I have never been able to locate any remnants of the Negro Hill Ditch west of the Negro Hill School house along the Mormon Island – Georgetown Road. Most likely the ditch is submerged in silt from Folsom Lake. In October 2016 I was able to hike down the Peninsula and take some good images of the foundation of the Negro Hill School House that sat next to the Mormon Island – Georgetown Road. Rusty pipes from the foundation trailed down the hill to the water’s edge. There I found a concrete and asphalt flat slab. The structure was situated just above the elevation line of the Negro Hill Ditch at approximately 375 feet in elevation. Perhaps this slab was for a pump house to lift water out of the Negro Hill Ditch for the school.

East of the Negro Hill School site I was able to pick out the elevation line of the ditch. Along my hike I found two more Native American grinding hole sites. I scared up some burrowing owls around these sites. They must like the little recesses created by the granite rocks.

I was alerted to the existence of the Deep Ravine and Hancock Creek aqueducts by Steve Hansen who regularly paddles up the South Fork arm of Folsom Lake. As I headed up Hancock Creek from the keystone arch aqueduct to connect with the Darrington Trail, I noticed the familiar site of grayish mine tailings in the ravine.

I was surprised to encounter a mine shaft easily 10 feet across and with an unknown depth. The entrance to the mine shaft, below the high water line Folsom and so close to the Darrington Tail, had to have been noted by the Army Corps of Engineers during their survey work for Folsom Lake. “How could such a dangerous mine shaft be left open for animals and people to fall into?”, I thought.

I researched Google Earth images of the area I found that the mine shaft was indeed filled with earth as late as 2012. Sometime in 2013 or early 2014, the fill dirt had sunken deep into the shaft leaving a gaping hole in the ground. It seems plausible that water from the lake and rain finally loosened the filled earth to slip pass a false bottom of the mine shaft.

Google Earth images showing the Hancock Creek mine shaft filled with dirt in 2011 and completely open in 2014

An open mine shaft is just one of the dangers, and welcome surprises, that one can witness while hiking around Folsom Lake. Like the other water canals, the Negro Hill Ditch seems like a marvel of engineering and hand-labor from the 1850s. From my perspective, the water canals, along with these unique stone aqueducts that still stand 100 years after being constructed and submerged under Folsom Lake for another 50 years, really should be granted historical status. But just like the Native American grinding holes, a testament to an earlier settlement of people in the area, they were dismissed. The pioneering water canals also seemed to have been relegated as inconsequential to the history of the area by the federal government.

Hancock Creek Mine Shaft Video

Short video of me tossing a couple rocks into the open mine shaft on Hancock Creek at Folsom Lake to determine the depth of the shaft.

Negro Hill Ditch Topographic Map Compilation

I stitched together three different USGS topographic maps to show the relative course of the Negro Hill Ditch in El Dorado County on the north side of the South Fork of the American River from Salmon Falls Bridge down to the Peninsula of Folsom Lake. Before the lake, this was the confluence of the north and south forks of the American River. You can down load the map below.

[wpfilebase tag=file id=1719 /]