From the shoreline of Granite Bay Beach Park at Folsom Lake you can probably see where Mr. Reppert was buried in 1849 in an unmarked grave far away from home and family. The death and burial of this gold rush miner comes to us from a fellow traveler and miner who wrote about his experiences in the 1892 book Experiences of a Forty-Niner.1

1849 Wagon Train to California

Reconstructed from daily journal entries that William Johnston kept from his landing at Independence, Missouri to his arrival along the North Fork of the American river, Experiences of a Forty-Niner is a first-hand account of one young man’s trek across the new American west with a wagon train headed to California. Written forty years after the original expedition, the author’s recollections are punctuated and colored with his observations of the Native Americans he encountered and opinions of fellow travelers who went on to fight on the confederate side of the Civil War.

Life on the Oregon Trail

If it weren’t for the life imperiling consequences of some of Johnston’s experiences, the events would be almost comical. Such as the time he leaves his clothes to dry by the campfire only to return to find singed clothing and a pair of boots burnt beyond use. At one point crossing the desert in Nevada Johnston is compelled to retrace the trail in search of his blankets lost when they fell from one of the wagons. After wasting energy and time looking for valuable bedding, Johnston is informed upon his return to camp that one of the wagon teamsters found his blankets but forgot to mention it to him.

Johnston’s daily journal reconstructs 1849

Prominent hill of the North Boat Ramp of Peninsula Campground. The northern most possible location of the Johnston gold mining party in 1849.

With the aid of frontier maps and subsequent stories about the Oregon Trail the author is able to fairly accurately name the various rivers, streams and other landmarks he passed. Johnston mentions passing prehistoric looking mounds in Kansas on May 2nd, 1849. These are probably one of the numerous Native American burial mounds. Unfortunately for me, the chapter pertaining to his gold mining activity and the death of fellow miner Mr. George Reppert is not as detailed. Aside from Mormon Island, the numerous mining bars such as Beal’s, Manhattan, and Horseshoe may not have been so named when Johnston was mining in the area. The lack of place names hinders an accurate placement of both the mining camp and burial site. (Picture gallery at end of post with thumbnails that can be enlarged)

A race to reach California

As the word of gold in California spread to the East Coast, Johnston and several of his friends decided to cross the continent in the spring of 1849. Some of his young friends opted to sail from New Orleans, trek over Panama, and sail up to San Francisco. The author decides to join a wagon train and travel over land via the Oregon Trail. Johnston arrived in Missouri in mid-March and watched anxiously as numerous wagon trains left weeks in advance of his own departure. He is reassured by their guide, Captain Jim Stewart, who had made the crossing on numerous occasions, that the wagon trains were leaving too early and there wouldn’t be enough pasture for either the mules or oxen.

88 days to cross the western frontier

Marked by a concrete bridge, this creek or stream may have been the one indicated by Johnston as next to his gold mining campsite in 1849.

Captain Stewart, renowned for his knowledge of maintaining mule trains, had promised to make the wagon train Johnston was joining the first to reach the Sierra Nevada mountain range in 1849. If the author’s account is correct, they were indeed the first to reach California in the middle of July. The author reckons the drive across the plains, over mountains, and through the desert took 88 days. For Stewart, it was almost a race as he had the wagon train moving before dawn, late into the evening and they never rested on Sunday. Consequently, except for an ill-advised detour through the Mormon settlement of Utah, for which Stewart was most angry at himself for undertaking, the author’s wagon train routinely passed other groups that had left weeks before they did.

Johnston convinced to mine for gold

We learn that William Johnston is not a gold miner at heart. He is looking for the big adventure of his life and he found it. After reaching Sacramento, Johnston drifts down to San Francisco where he meets up with other friends James Murphy, George Barclay and George Reppert. Johnston was actually considering continuing onto Hawaii or China but is persuaded to try his hand at gold mining. So the four 49’ers set out for the north fork of the American river where Johnston knows some of his previous wagon train mates had set up camp.

Folsom Lake may have washed away Reppert’s grave site

Subsequent mining along the north fork of the American river coupled with the construction of Folsom dam creating a reservoir that covers the mining bars of the 19th century makes it is virtually

Burial mound of George Reppert or just rocks? Across from Granite Bay Beach Folsom Lake State Park.

impossible to locate the actual spot where the author mined or the burial site of Mr. Reppert. But Johnston does give us some clues as to the site of the mining camp and surroundings. But the lack of specific landscape details on top of impediments imposed by the water in Folsom Lake make finding the original locations all but impossible. However, I will use any excuse in the name of history to hike around the Folsom Lake and the numerous trails.

Departing Mormon Island for the North Fork Camp

After Johnston and his mates crossed the South fork of the American River at Mormon Island they climbed up the steep embankment out of the river bed and walked another hour to the mining camp established by fellow mess mates on the plains McBride and Scully. The description was that the walk was relatively easy as the “valley of the north fork of the American river” came into view. The mining camp was situated next to a creek not far from the river.

Each one started with a load strapped to his back or otherwise carrying what he could ; and by a path leading up the steep hill-side, we ascended leisurely until the summit was reached, after which the way was almost level. There was an unbroken forest of stately trees, mostly pines, the entire distance. An hour’s walk brought us in sight of the valley of the North Fork, when by a precipitous path, we descended to the camp of our friends. Mr. Scully was absent, and we made the rocks and hills ring; with our united voices shouting halloo ! when at length came forth from a cleft where he had been prospecting. Wearing a red flannel shirt, pants rolled to the top of his boots, his head sheltered by a great felt hat, with bushy whiskers almost covering his face, and carrying a pick, shovel and pan, he was the very personification of a California miner ! – pages 272 – 273

Distance and creek are in question

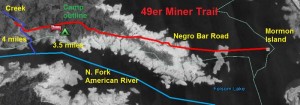

With relative certainty we know that Johnston and his party traveled up the east side of the north fork of the American river from the crossing at Mormon Island. Today this is known as the peninsula being formed by the incoming waters to Folsom Lake from both the north and south forks of the American River. If the miners hiked for approximately one hour, they would have traversed anywhere between three to five miles. While there are several ephemeral streams that empty into the north fork of the American River, the one that may have reached was where the trail climbs northwest from the river which is present day Rattlesnake Bar Road on the north end of the Peninsula Campground.

When is the American River a stream?

Granite rocks arranged for some purpose, possibly a mining campsite. Folsom Lake, Peninsula Campground, North Fork American River.

In describing his several weeks in the north fork mining camp Johnston tell us a little bit about landscape.

We sometimes tried other “diggings,” but never with as much success as in the place originally selected. Once we crossed to the opposite side of the stream, where the rocks bordering the river were higher and more precipitous, but were not repaid for our labor. – page 278

It is unclear if Johnston’s reference to “stream” is actually synonymous with the American River or if in fact it is the creek that runs along Rattlesnake Bar Rd. and empties into the river. On the north side of this creek is the hill on which the day use Peninsula Campground North Boat Ramp is located. This hill at 544’ elevation marks a transition where the east side foothills are closer and steeper to the American River which makes hiking and camping more difficult.

Hiking the peninsula trail

As I have hiked from close to the original Mormon Island crossing up to the Peninsula Campground, a one hour trek up to just south of the boat ramp would be within reason. (This hike occurred when Folsom Lake was very low during the drought of 2013-14.) The distance between Mormon Island and the creek at Peninsula Campground is about 4 miles. I’ve also hiked up to Anderson Creek, another 1.3 miles in distance, and further up to Granite Ravine, another mile north. While both of these places have streams, the hike wouldn’t have been as easy or as short as Johnston indicates. Consequently, I conjecture that the most northerly mining camp site would have been at the base of the North Boat Ramp hill just inside the Peninsula Campground.

Folsom Lake covers most river side mining camps

In attempt to wander around looking for potential camp sites of this old 49er party, I started at the North Boat Ramp and worked my way south down the peninsula. On July 26, 2014, the day of my excursion, Folsom Lake elevation was at 405 feet. With the river bed at 230 feet, there was 175 feet of elevation that I didn’t have access to. In short, most likely Johnston’s mining camp and Reppert’s burial site may still have been under water for all I knew.

Johnston call it quits

Granite rocks arranged for some purpose, possibly a mining campsite. Folsom Lake, Peninsula Campground, North Fork American River.

In early November of 1849 with rain falling and the prospect of what Johnston thought would be heavy snowfall, the author and Murphy decide to leave the mining camp after only seven weeks of gold mining and head home. Mr. Reppert had contracted dysentery on the ocean voyage to California and had never really recovered. Johnston notes how Reppert rarely left the camp tent and failed to heed their admonishment to travel to Sacramento for medical treatment.

Marking George Reppert’s grave site

While in Sacramento waiting for their wagon load of camping gear to be brought to them, Johnston and Murphy learn of Reppert’s death.

After a toilsome march on account of the mud, and as hurriedly as possible, we reached camp on the afternoon of the following day, and found Mr. McBride sitting near the tent, from whom we learned the particulars of Mr. Reppert’s death. Soon after we walked to the hill top to visit the place where our friend lay buried. A lofty oak at the head of the grave, and the broken turf covering the mound beneath which his body lay, was all that marked the spot. Mr. Murphy’s experience in carving, when at sea, enabled him to prepare a suitable tablet, which was nailed to the oak; meanwhile Mr. McBride and myself brought from the river bank a number of stones with which to further mark the solitary resting place.After a toilsome march on account of the mud, and as hurriedly as possible, we reached camp on the afternoon of the following day, and found Mr. McBride sitting near the tent, from whom we learned the particulars of Mr. Reppert’s death. Soon after we walked to the hill top to visit the place where our friend lay buried. A lofty oak at the head of the grave, and the broken turf covering the mound beneath which his body lay, was all that marked the spot. Mr. Murphy’s experience in carving, when at sea, enabled him to prepare a suitable tablet, which was nailed to the oak; meanwhile Mr. McBride and myself brought from the river bank a number of stones with which to further mark the solitary resting – pages 297 – 298

Time to go home

The death of their camp mate had changed the tone of the entire mining party. They all decided to leave the mining life on the river behind.

After a good night’s rest the tent was taken down, and strapping on our backs all we could in this way carry, and making arrangements for the transportation of what remained, we started in single file up the narrow path which led to the top of the hill. Before leaving behind forever scenes which in after life would become hallowed in our memories, by the recollections of the many pleasurable hours which our mining camp had afforded, we paused on the brow of the hill to take a farewell view of all around. Below lay the valley, wild and picturesque, through which the beautiful North Fork, rock bound, threaded its way, as noisily it dashed onward singing the song of ages. There were the cliffs with beetling brows overhanging the stream, among which we had delved for gold. And there the smoldering campfire about which so many merry hours went by. About us were the giant forests abounding with game with which our table had been so sumptuously furnished. And here, close at hand, was the grave of George Reppert! – pages 299 – 300

More Pacific and Atlantic adventures

Johnston recounts many illuminating stories about San Francisco, the sailing voyage to Panama, crossing the isthmus and the final boat trip home. Over the next several months it would take to make it back to Pittsburgh the author is taken quite ill with fever. Mr. Murphy is his constant companion and nurse. After witnessing five burials at sea for men who had expired aboard their sailing vessels, Johnston expresses his eternal gratitude to his steadfast companion James Murphy who undoubtedly kept him alive during the journey home.

Outlines of the past

Distinct outline of old mining camp near Peninsula Campground in El Dorado County, Folsom Lake. Google Earth view.

As I wandered down the peninsula in the July heat I stumbled upon the outlines of an old campsite and what looks to be a burial mound. Folsom lake has alternatively eroded the soil below the high water mark and also deposited that soil filling natural depressions. Most of the oak trees below the water either died or were cut down before the reservoir was filled. Almost 60 years after they began to fill Folsom Lake, the stumps of oak trees remain.

Man-made or natural occurrence

It is hard to discern what is a purposeful collection of rocks placed by men or what is just a natural accumulation of stones from some flooding event in the past. I did find one mound of rocks, of different origins, arranged approximately six feet in length and 2 feet in width that fits what I would consider to be a burial mound. Not that it is. Not far from the mound of rocks is the outline of more granite rocks intersecting at nearly right angles with two additional rows in the middle From a Google Earth image it’s clear these granite rocks were placed there for a purpose. A camp site perhaps? Both of these sites are below the high water line of Folsom and have either been washed of debris or collected soil from above.

A spring or a leak?

Is this a spring or a water leak that flows into Folsom Lake the outline of an old mining camp near the Peninsula Campground at Folsom Lake?

The unnatural mound of rocks is but a few hundred feet from the campsite foundation. The mound doesn’t fit with Johnston’s description that Reppert was buried on a hill, but the river and the valley are in view from the site. This collection of “rocks” is not as far north as the creek along Rattlesnake Road, but an ephemeral stream does run through the area. Curiously, there is a spring that pops out of ground right below the campsite foundation. Whether it is natural or a leak from the Peninsula Campground water system that sits on the hill above the site is unknown.

Hauling sacks of dry earth

I also tend to believe that the Johnston mining camp was closer to the river. The author details how they dug in dry ground and transported the earth in sacks to be washed in the river with a cradle.

The tent we brought with us was sufficiently large for the newly formed mess, and we pitched it near to the base of the hill under the shade of two wide spreading oaks… After a good night’s rest and an early breakfast we went to work—this was on Friday, September 14th. The site chosen for digging was scarce more than a stone’s throw from our tent, and we moved but slightly from it during our stay in the mines. From this point the earth had to be carried in sacks to the edge of the river, where it was emptied into two cradles for washing. It was a rough, precipitous descent of rock, twenty feet or more in extent, over which this carrying was done.

The earth in which gold was found in this vicinity lay total depth of from four to six feet upon the top of rocks. Usually we cast aside as worthless, a layer of sand, or sometimes sand mixed with earth; all below this was carried to be washed, and the nearer we approached the rock, the greater were the returns. When the surface was reached, it was scraped and swept with great care, for here the gold could be seen, lying in shining particles. – pages 273 – 275

Did I walk over Reppert’s grave site?

I doubt that I found the burial spot of Mr. Reppert. There are many spots north of Mormon Island on the east side of the north fork of the American River that could have accommodated the mining operation, camp and hill that contains the remains of Mr. Reppert. But I am confident I traversed over some of the same ground as the Johnston mining party. I also think there is a reasonable probably that Mr. Reppert’s burial site, while most likely under water since 1956 when Folsom Lake was filled, is within the panorama of the peninsula as viewed from Granite Beach State Park.

1891 trip starts book manuscript

Well preserved oak tree stump and tap root at Folsom Lake. 60 years after the lake was filled.

William Johnston didn’t formally commit his journal and recollections of his time as a gold rush pioneer until after he re-visited California in 1891. He notes that after forty years both San Francisco and Sacramento have completely changed because of the building boom. He travels up to the North Fork Camp to rekindle old memories of the past.

Of course I visited the site of our mining camp on the North Fork of the American River, and there was a certain melancholy satisfaction in this. Perhaps of all places in California that I once knew, this less than any had undergone change, and I may predict with some degree of certainty that it will never be changed. Rocks and sand have so full possession that they cannot be dispossessed, and on this account I had great difficulty in going about.

The site of the camp, and where we dug among the rocks for gold-bearing earth; the precipitous descent over which the bags of dirt were carried, and the spot down by the river where our cradles were rocked, were all of them places which through many years have had a strong hold on my memory, and kindled afresh many recollections of the past. – pages 384 – 385

Hiking over hill tops looking for George Reppert’s grave site loaded up my socks and shoe laces with lots of weed stickers.

Change in the form of a dam

Alas, the old north mining camp did change. In a good year of precipitation the mining camp is put under 230 feet of water when Folsom Lake is full. I was the solitary hiker as I passed several groups of families that were enjoying the cool water of Folsom Lake on a very hot day. Could they have suspected I was looking for the grave of man dead over 150 years? Many people have died and were buried on the river. From Native Americans to infirmed miners, we have probably all unwittingly stepped over the grave site of an early American that sought out the river to sustain and enhance their life.

John H. Plimpton started the hike

The Experiences of a Forty-Niner was first brought to my attention while reading through the John H. Plimpton collection in the Placer County Historical Archives room. There are over five binders of notes, articles, photos, newspaper clippings and excerpts of books collected by Mr. Plimpton on the North Fork of the American River. Inserted in the collection were references to Johnston’s book. While none of my hiking or research has added much new information to the history of the north fork, it has kept me curious and occupies my time to learn more about a gold rush river perpetually covered by a man-made lake.

1.By William G. Johnston, Pittsburgh, 1892, University of Pittsburgh Library

Click image to enlarge