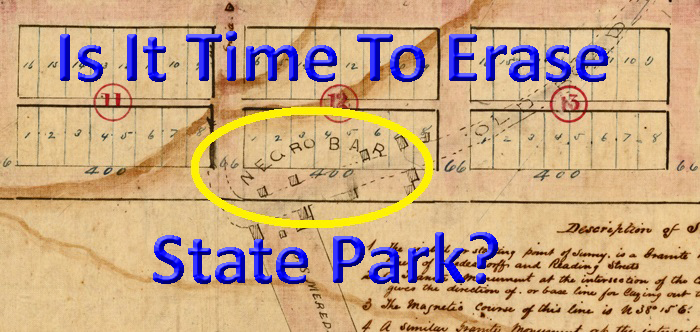

As a child growing up in Sacramento, I drove by the Negro Bar State Park entrance hundreds of times. As I became more culturally aware in the 1980s, I would internally flinch at the name as I passed by on my way to Folsom. Even as I began to study the history of the Folsom region in earnest, I was uncomfortable with the inferred racial animus of the name. In the summer of 2020, with systemic and institutional racism in the forefront of the nation’s consciousness, perhaps it is time to change the name of Negro Bar State Park.

Negro Bar Historically Important

As I have continued my historical research of the region, which includes numerous blog posts, two books, and work on a third book focused on the Folsom-Sacramento area, I have come to view Negro Bar as just another Gold Rush era location. It’s possible that I have become inured to the name. However, through my historical research, I have not found the title Negro Bar was meant for anything other than for the designation of a mining area on the American River that had a predominance, at one point, of Black Americans. The designation is certainly racial, but not necessarily racist.

This is not to say that there was not racism among the miners of 1849. The designation of Negro Bar occurred because there were people of color mining at that location. It was similar to other place names like Rattlesnake Bar for snakes, Horseshoe Bar because of the shape of the river, Mormon Island for the numerous men of the Mormon faith who mined there, or Salmon Falls for the fish on the South Fork of the American River.

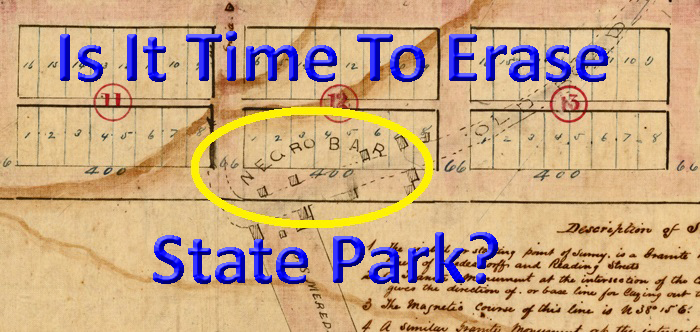

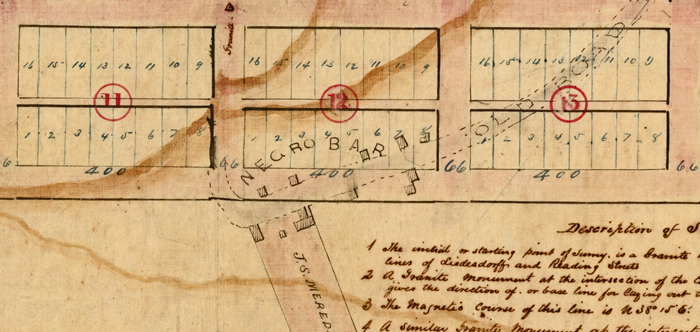

This particular mining bar was most likely christened as Negro Bar in early 1850. One of the first mentions of Negro Bar is from the Sacramento Transcript newspaper, May 9th, 1850, alerting the public to elections for constables and Justices of the Peace. Negro Bar was in the 6th District encompassing Mormon Island and other settlements. Negro Bar just was not a mining camp, it was considered a settlement where people had constructed long-term accommodations such as cabins, hotels, stores, and most importantly, saloons.

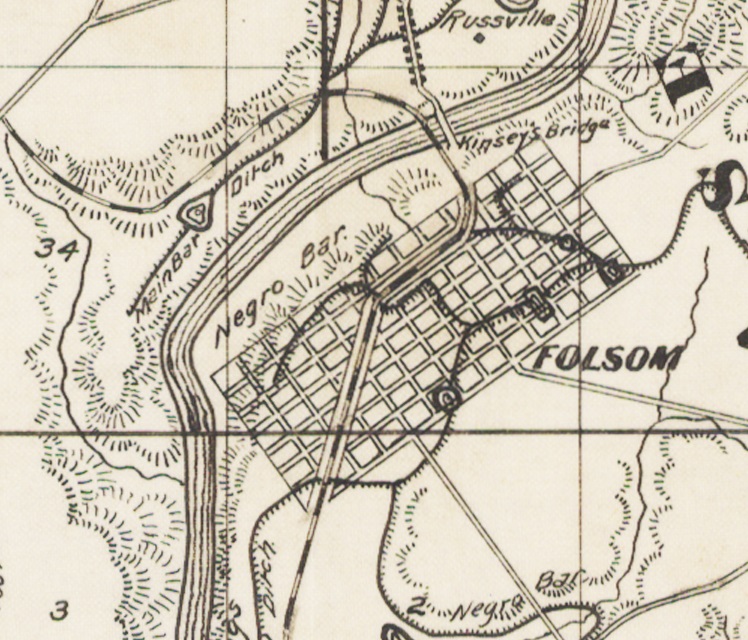

The Sacramento Transcript also reported on the Sacramento County census of 1850 in their November 16th edition noting that Negro Bar had approximately 360 inhabitants, twenty more than Mormon Island. From mining bar to town, Negro Bar had become permanent. Before Folsom was created on the bluff overlooking the American River, Negro Bar was referred to as the terminus of the Sacramento Valley Railroad.

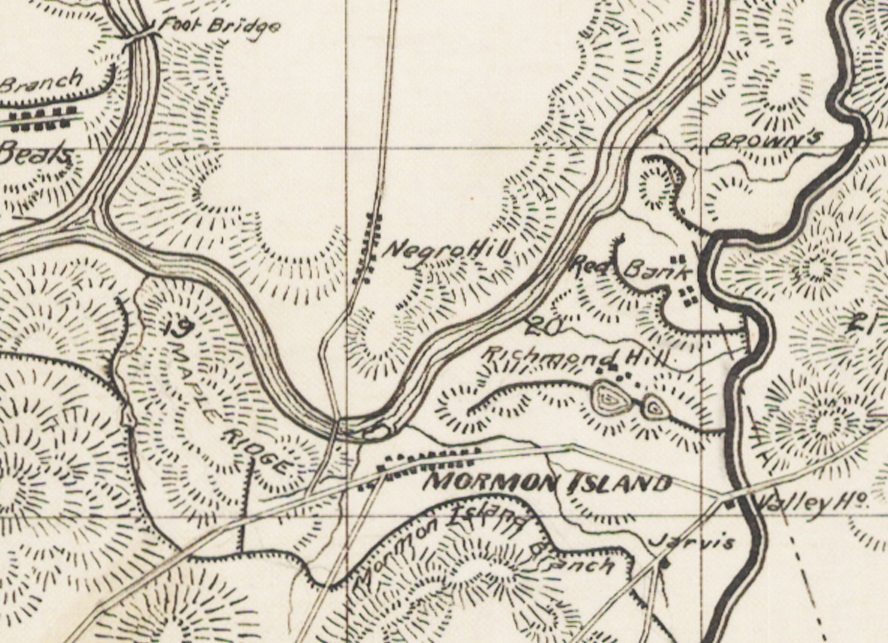

From Negro Bar to Negro Hill

When gold production at Negro Bar declined, many Black Americans migrated to a hill overlooking the South Fork of the American River. It was then designated Negro Hill. But these were not the only locations during California’s Gold Rush to receive the racial moniker. There were Negro Bars, Bluffs, Flats, Gulch, Slide and Tent mining designations scattered across several foothill counties.

While the small settlement known as Negro Bar would give way to the town of Folsom, the actual mining location on the river would retain its original designation. By the time Folsom came into official existence in 1856, Negro Bar was being mined by a large number of Chinese men. Gone were most of the white and black men who originally mined there.

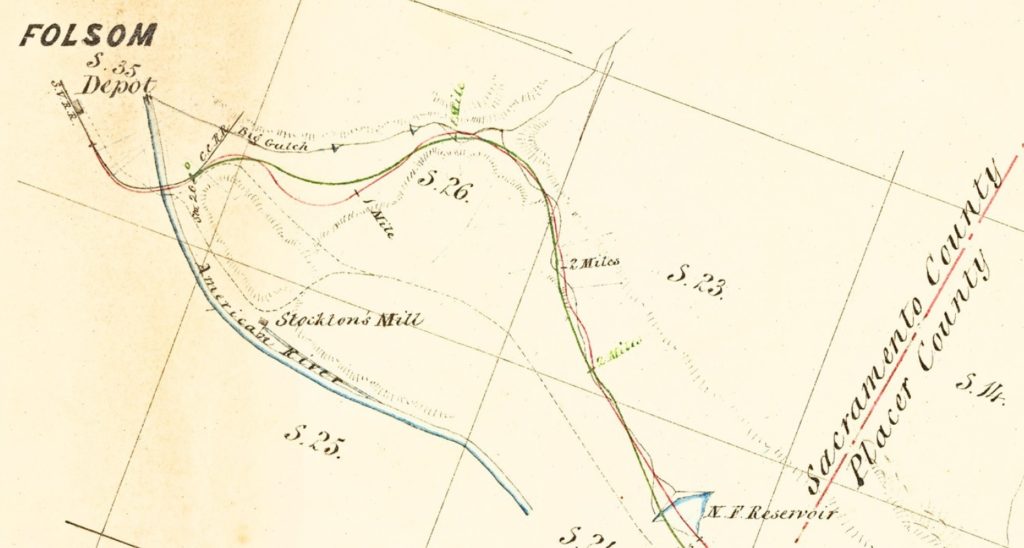

If you want to split historical hairs, Folsom is the town Theodore Judah laid out along the Sacramento Valley Railroad as it made its way up towards Marysville. Folsom’s original name was Granite City. When Captain Libby Folsom died 1855, the proposed town was renamed in his honor. Negro Bar was technically still in existence down the hill from Folsom, above the American River.

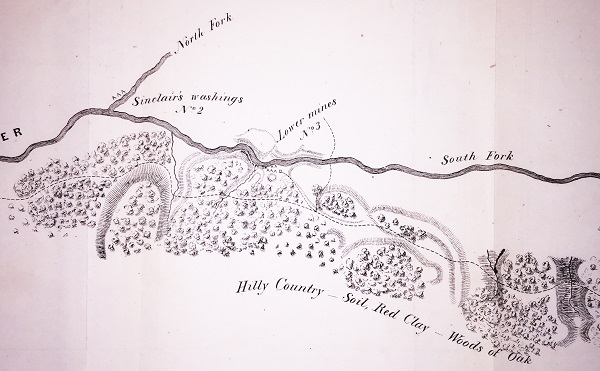

Several mining locations had their names changed. Sinclair’s washings, noted on an 1848 map, would become Beal’s Bar. Big Gulch, directly opposite Negro Bar, would become Russville. After the embarrassing failures of mining promoter Russ collapsed, the small little village across the river from Negro Bar changed its name to Ashland. The eastern end of Negro Bar State Park encompasses Big Gulch. To put any confusion to rest, the original Negro Bar was on the south side of the American River while the State Park is on the north side.

This brief history of Negro Bar is not meant to ameliorate any perceived racism associated with the name. Black Americans in California were second class citizens during the Gold Rush era. They encountered slightly better treatment than Native Americans or Chinese men. I can quickly point to the use of the racial epithet for Black Americans used in newspapers, especially as the country barreled toward civil war.

The miners were not in favor of slavery in California. This position did not come from some enlightened human rights epiphany upon entering California. The miners did not want the unfair competition of slave owners bringing their slaves to work the mines. There was a general attitude that an able-bodied man lived or died, remained poor or struck it rich, based on his own work. Every man, regardless of color or country of origin, was given a certain amount of respect for undertaking the laborious occupation of miner.

All the men who entered the mining districts in California were slaves. They were slaves to their lust for gold and it would not stop with a little gold panning. Miners systematically destroyed the American River where ever there was a hint of gold dust. First they dammed and diverted stretches of the river. When the water canals were constructed, above the river, they started sluicing the banks and benches. Then they started directing a stream of water at the hillsides in the form of hydraulic mining. Finally, huge dredging machines would excavate large swaths of the land in and adjacent to the river. The miners left a desolate waste land of mining debris when the cost of extracting the gold was greater than the returns.

The early miners at Negro Bar and other locations were essentially homeless people by today’s standards. They just had the potential of creating an income by mining. They lived in shacks, tents, and cabins. They had to contend with rattlesnakes, bears, brutal summer heat, freezing winter rain, floods, lack of food, drunken brawls, and thieves. Men of color or a different nationality also had to absorb the racism and bigotry of white men from the eastern United States.

The Gold Rush has been mythologized and romanticized. Its only been in the late 20th century that we began to evaluate the cultural stew created by the invasion of gold seekers into California in the 1850s and its impact on local customs and laws. Thousands upon thousands of pages of history have been written by white men about white men who came to California for gold. By default, white men – those who controlled government, elected offices, and newspapers – wrote the history and cemented the names of mining regions.

The experience of Black Americans and their contributions had been mere footnotes or commas in the printed saga of California of the 19th century. The visible traces of Black Americans of the Gold Rush are the names of places such as Negro Bar, Negro Hill, and the Negro Hill Ditch. Both Negro Hill and the ditch only exist on maps as Folsom Lake now covers both. Similarly, Negro Bar only partially remains above the high water of Lake Natoma.

Federal Government Racism On Display

The racial epithet for Black Americans and entrenched systemic racism was codified by the federal government. It was the United States Geological Service and the Army Corp of Engineers that printed and engraved the n-word in the Folsom region. I was shocked when I reviewed the 1941 USGS Folsom Quadrangle map and saw that word in place of Negro Bar. When the Army Corp of Engineers relocated all the cemeteries from what would be Folsom Lake to the Mormon Island relocation cemetery, the n-word was stamp on grave markers for the remains of people from Negro Hill.

Fortunately, the USGS map was updated in 1954 with the offensive word removed and the grave markers were replaced in 2011. The introduction of the n-word on official documents and monuments was initiated by a racist at the federal level. I have come across no local or state maps that included the n-word in place of negro. I’m sure that some of the locals in the area also used the racial epithet to describe Negro Bar or Negro Hill.

This brings me back to the question as to whether the park name Negro Bar should be changed. From a geographical position it is incorrect. Negro Bar was on the opposite side of the river. A more appropriate name would be Big Gulch State Park. A substitute could be Ashland, the successor to Big Gulch. Another possibility is calling it the Railroad Park because at one time in the 1860s were three railroads overlooking Negro Bar: California Central Railroad, Sacramento, Placer and Nevada Railroad, and the Sacramento Valley Railroad.

Someone with knowledge of the California Parks Department might be able to share the rational for calling the current park location Negro Bar. Even the smallest amount of investigation would have revealed that the park site was not the original Negro Bar, but Big Gulch. The same research yields insights into the importance of Negro Bar as not only a mining spot, but a river crossing, town, and railroad location. Perhaps it was the importance of the Negro Bar location that factored into the California Parks Department’s decision to honor that little community that also accommodated Black American miners.

California can change the name to whatever makes the public happy. Negro Bar will not go away, but if the name is changed, it will be forgotten. For example, Sinclair’s washings, was the location of John Sinclair’s mining operation in 1848. Sinclair was part of the important history of Rancho del Paso and Sutter’s Fort. He left California in 1849, with a fortune in gold, and died before reaching New York. His successor at the mining location was a Mr. Beal, whose name now graces old maps and Beals Point Park at Folsom Lake. However, I would argue that Sinclair was more influential in the development of Sacramento and American River mining than Beal.

Any modest legacy Black Americans had as early pioneer gold miners will slowly fade away with a name change. But this is no different from the almost complete erasure of the Native American presence in the area. Erasing the past is what white men do best.