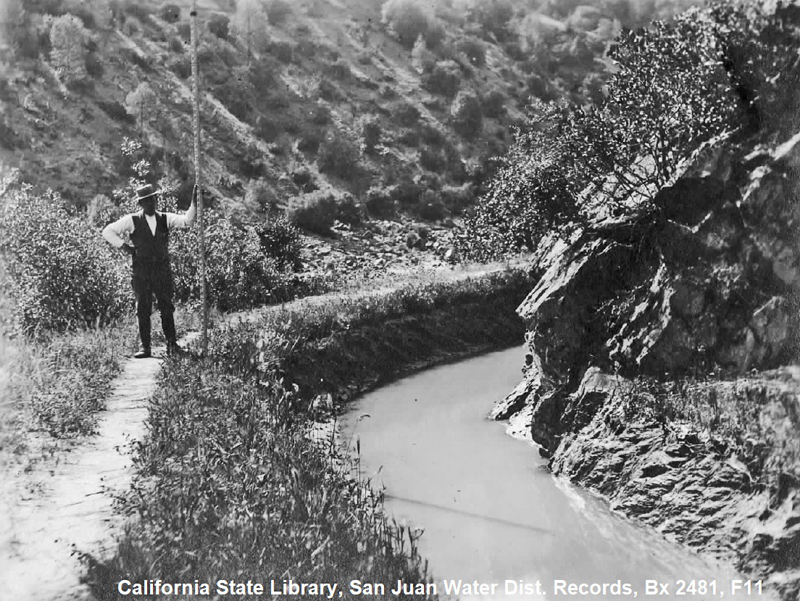

The last years of the North Fork Ditch were like the early years in the 1850s. It was a constant struggle to keep the water flowing in the ditch or water canal from Auburn down to Sacramento County. The ditch was constantly failing, threatening the supply that an increasing post World War II population depended on for water.

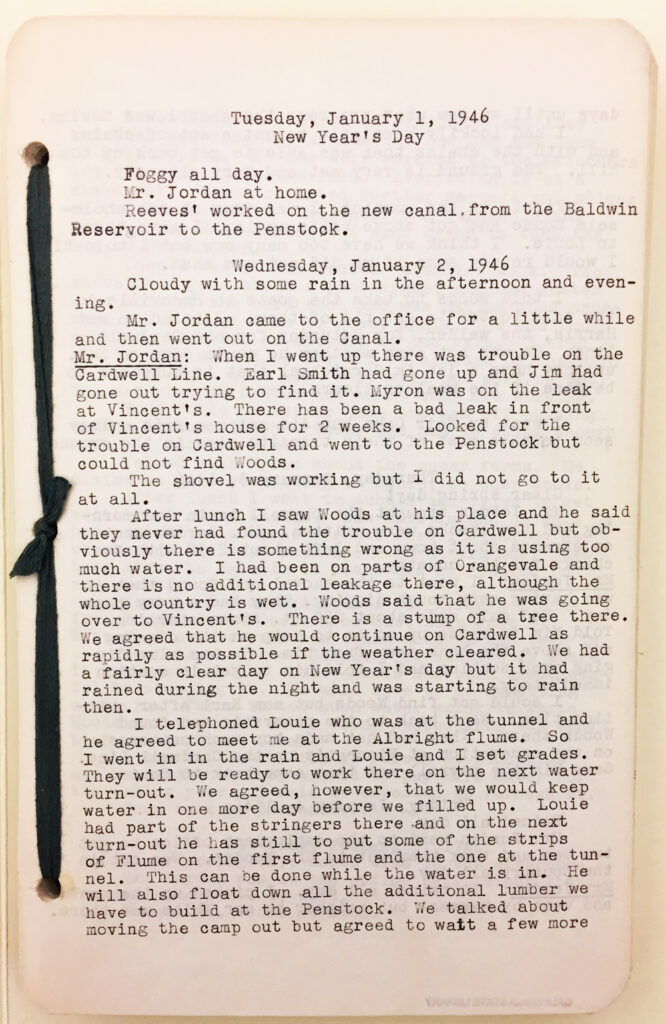

We know the tenuous state of the North Fork Ditch from a journal kept by Loring K. Jordan, General Manager of the North Fork Ditch Company. The extraordinary journal, spanning two years, 1946 and 1947, is a manually typewritten journal located in the San Juan Water District records at the California State Library. The journal spans 380 pages with almost daily entries by Jordan or his assistant Miss Link.

Loring Jordan Records Last Years of North Fork Ditch

The journal not only details the numerous issues that Jordan dealt with on the North Fork Ditch, but it also records daily weather, local events important at the time, and gives a glimpse of the Sacramento region in the late 1940s. It is not clear why Jordan kept such a detailed journal of his activities. While he had a good relationship with the Board of Directors of the C.W. Clarke Company that owned the North Fork Ditch, I think he wanted to memorialize many of the challenges he faced.

The Board of Directors were in San Francisco and removed from the management and operational problems the dam and water canal faced. After reading through the two years of journal entries, I was absolutely impressed with the amount of work Jordan undertook daily. Jordan was the sole administrator of the North Fork Ditch. He oversaw all the reports, tax returns, water applications, rate increases, and engineering projects of the water canal. Jordan was the face of the North Fork Ditch to the wholesalers and retail customers that he met with frequently.

Jordan was physically present on the ditch almost every week and was part of the labor to repair the ditch when it would catastrophically fail. In addition, Jordan also managed the C.W. Clarke Co. property in Fair Oaks and down in the Sacramento – San Joaquin Delta. It was a physically demanding job for a 58-year-old man who had suffered a stroke when he was a young adult.

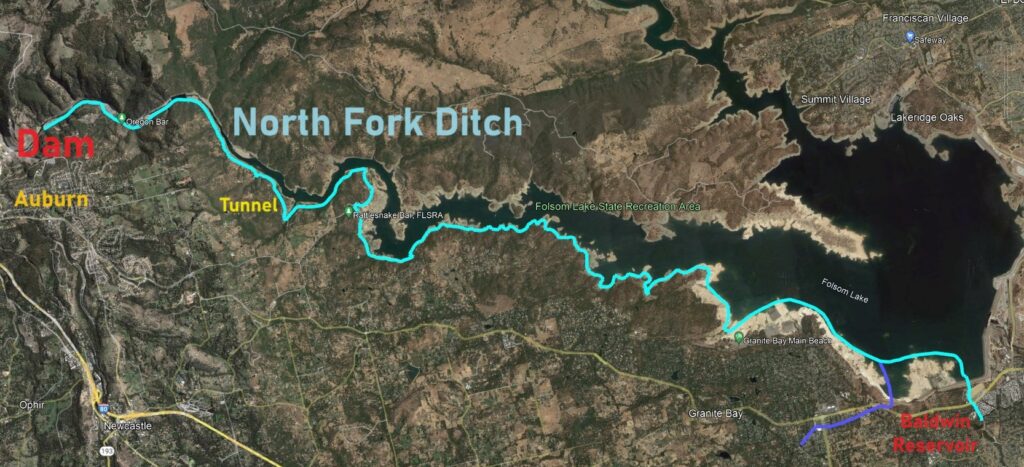

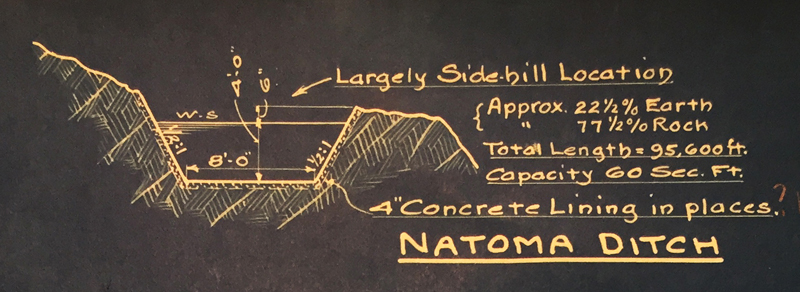

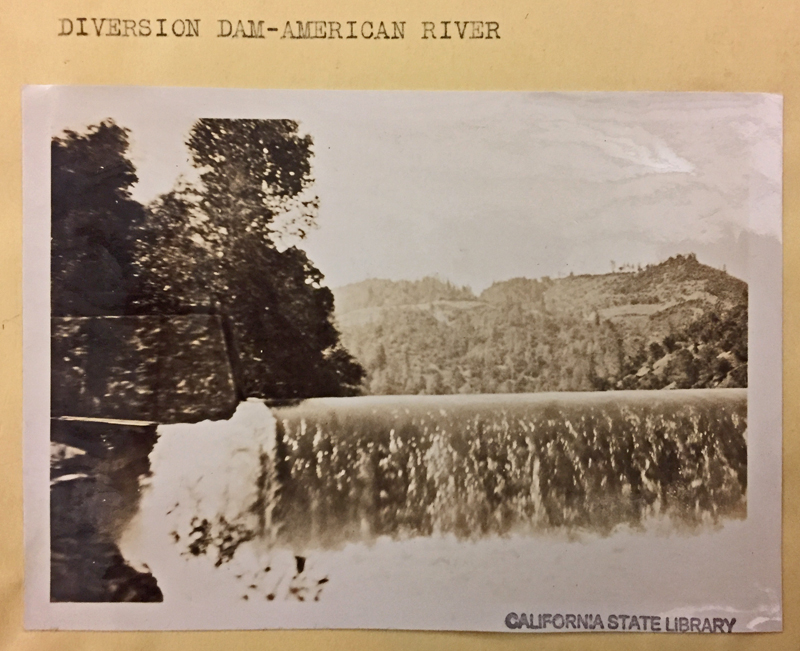

The main water canal of the North Fork Ditch was 22 miles in length beginning at a dam below Auburn on the North Fork of the American River. From the head gates on the dam, reconstructed in 1899, the water was diverted into the main canal that ranged from 6 to 8 feet across the top, 4 to 5 feet on the bottom, with sides of approximately 5 feet in height. The dimensions depended on the terrain.

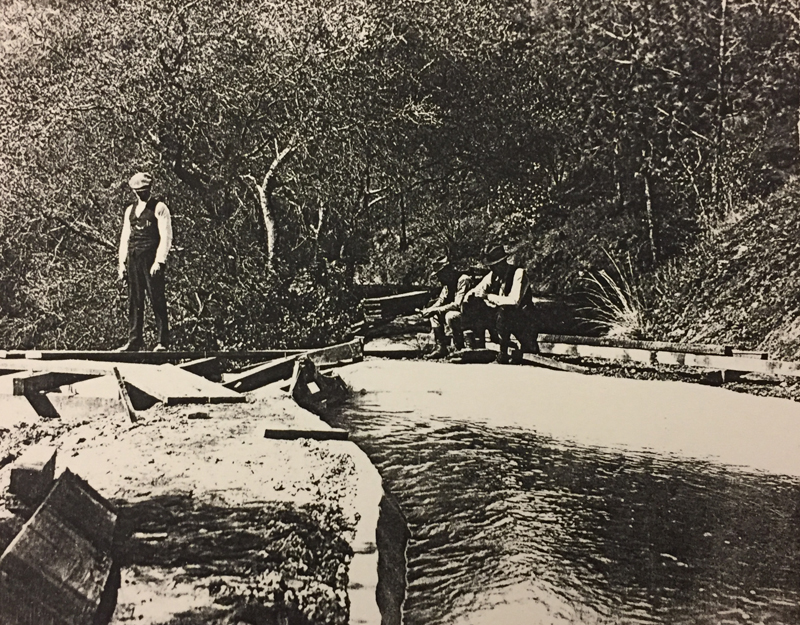

At several locations, the water was carried in a wooden or metal flume around steep hill sides or over ravines. There were long stretches of earthen canal where portions had a concrete lining installed to reduce seepage. The North Fork Ditch closely followed the original 1854 water ditch. In his journal, Jordan refers to the ’28 and ’32 canals where a new canal was dug either above or below the original ditch line.

The ideal slope for the water canal was a 3 to 4 foot declination per mile. The ideal slope was not always followed by the original ditch. Consequently, changes to the ditch had to be made. All the changes were made to improve the flow so they could push the maximum amount of water during the hot summer months from the beginning to the end of the line. Jordan notes the several tunnels that the ditch flowed through on its course down to the reservoirs.

While the water canal could fail at any time, it was most vulnerable during the summer months when it was carrying its maximum capacity of close to 3,000 inches. In the 1940s, Jordan was still referring to flow in terms of miner’s inches. A miner’s inch was approximately 9 gallons per minute based on 4 inches of head. This meant the canal was carrying 27,000 gallons of water per minute at full capacity.

The maximum flow translates into 3,600 cubic feet per minute. The Ditch Tender’s Report of July 1947, as measured at station 0+2884 below the dam, recorded an average depth of 3.28. The total water passing by that location was calculated to be 4,426 acre feet. The bulk of the water flowing was to serve the wholesale consumers of Orangevale, Fair Oaks, Citrus Heights, and Carmichael.

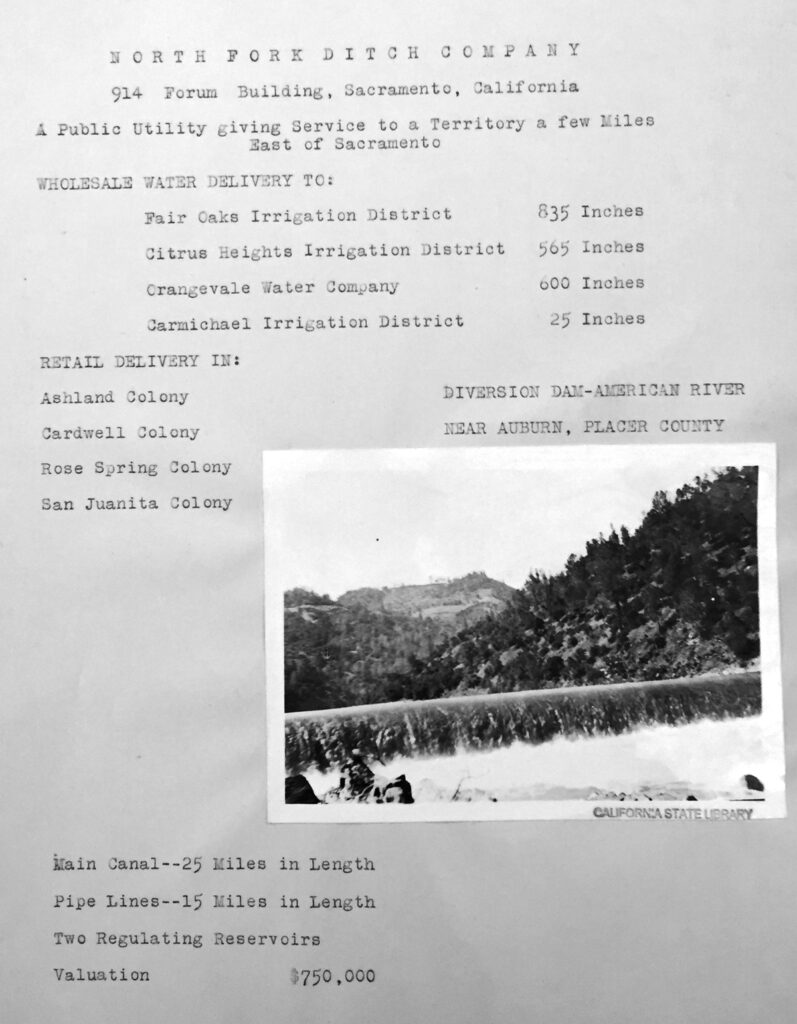

A report Jordan prepared for the Public Utility Commission, for the purposes of a water rate increase, listed the wholesalers and the supply they demanded during the summer.

Fair Oaks Irrigation District 835 inches

Citrus Heights Irrigation District 565 inches

Orangevale Water Company 600 inches

Carmichael Irrigation District 25 inches

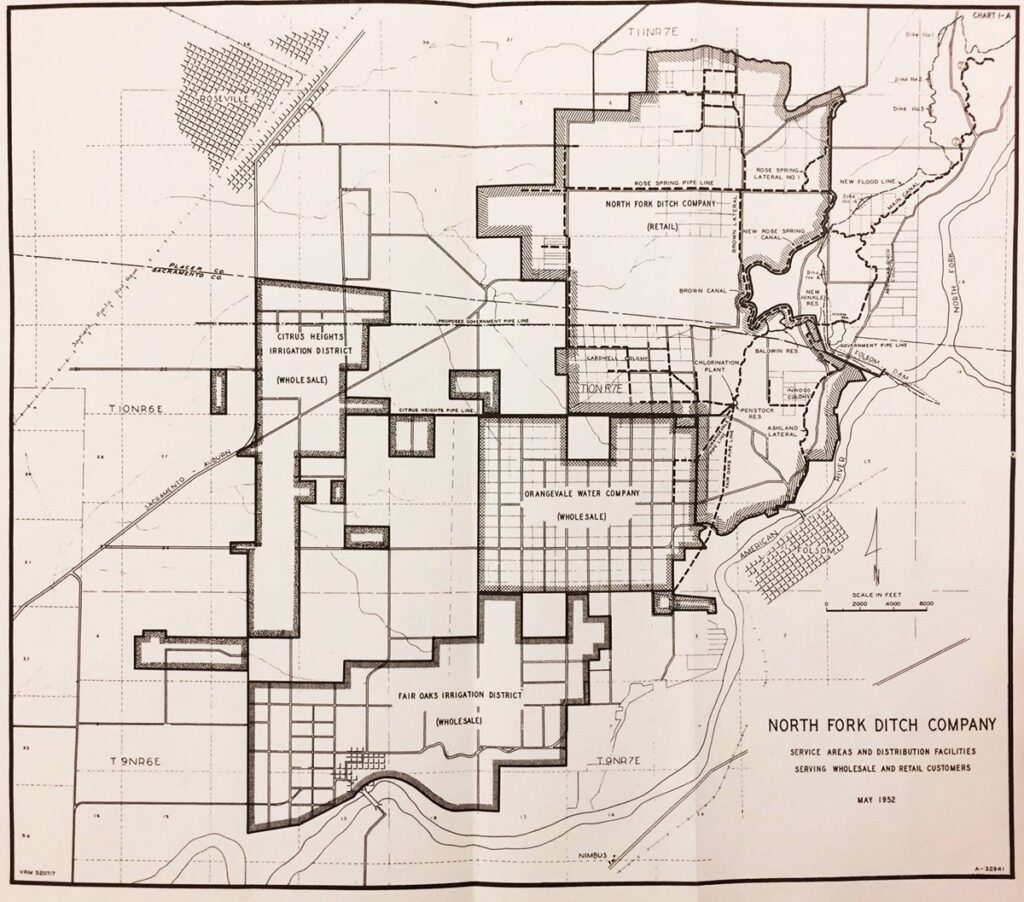

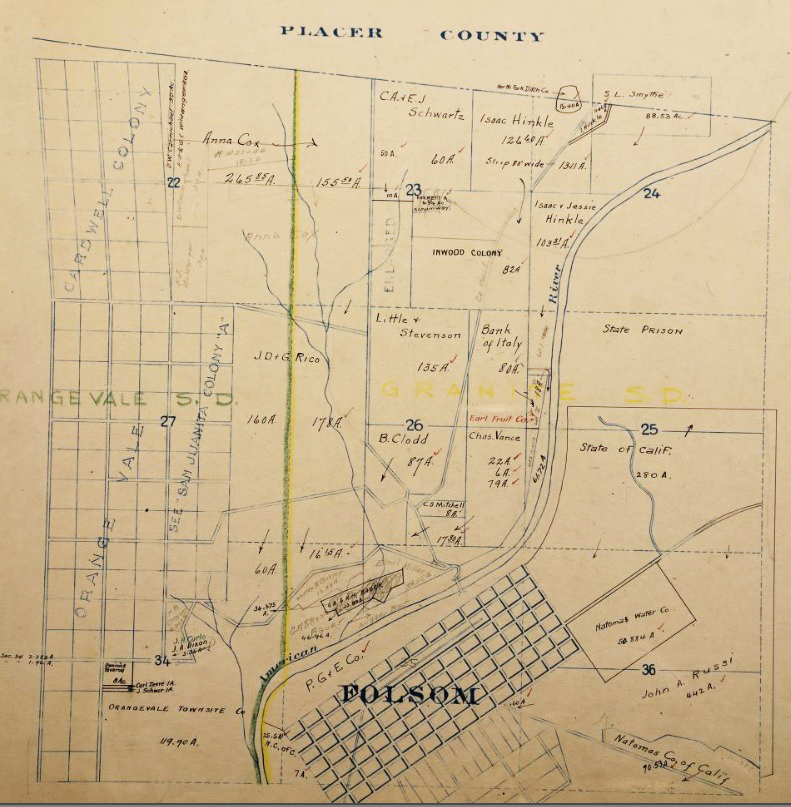

The wholesalers accounted for 2,025 inches of water. The North Fork Ditch also supplied water to retail consumers. While there were a few customers along the main line, most of the retail consumers were near the end of the line in Placer and Sacramento counties. The retail consumers were broken into zones referred to as the Ashland Colony, Cardwell Colony, Rose Spring Colony, and San Juanita Colony.

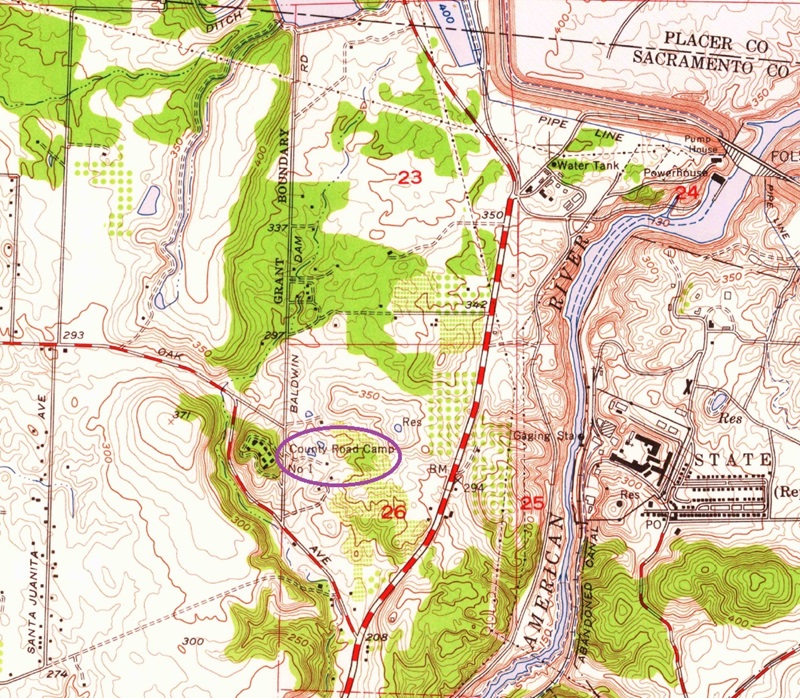

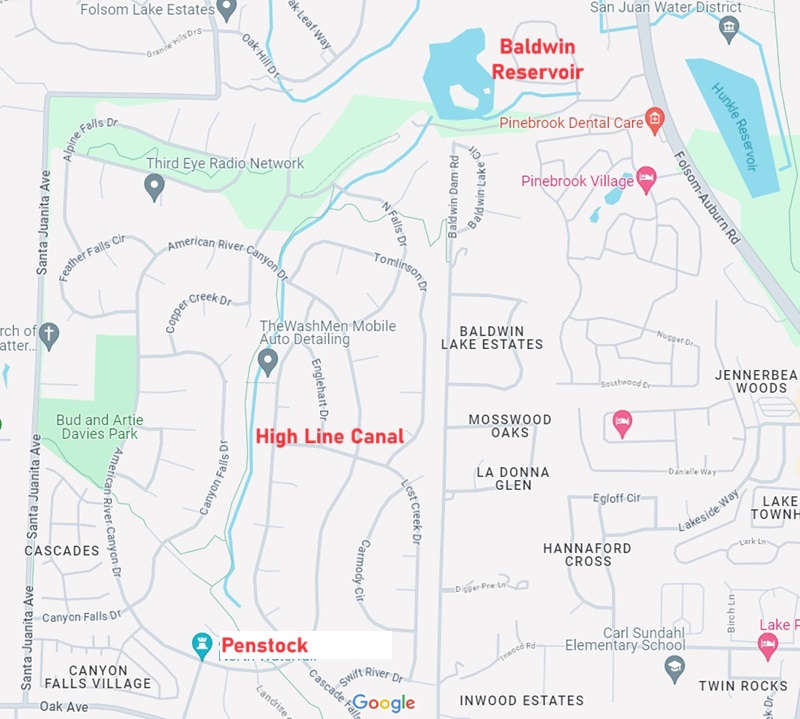

The main canal was open to whatever fell into it. The water was delivered to the Hinkle and Baldwin reservoirs. Hinkle reservoir mainly supplied customers such as the Earl Fruit Company to Ashland, the corner of Greenback Lane and Auburn-Folsom Road. Baldwin reservoir fed the small Penstock reservoir, above present-day Oak Avenue, where the water then filled pipes that led to Cardwell Colony, Orangevale, and Fair Oaks.

One of the challenges Jordan faced was the emergence of water science that could detect Escherichia coli in the water. The bacteria had been found in water supplied by the North Fork Ditch in Citrus Heights. He was being pressured to chlorinate the water by the state and county health departments to eliminate the bacteria. However, treating the river water was low on Jordan’s priority list when it came to problems with the North Fork Ditch.

Water Canal Failures

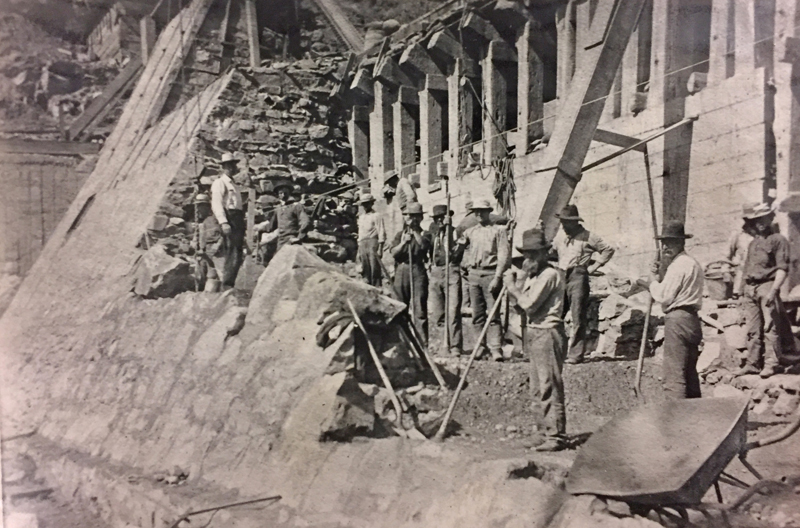

When the canal experienced a break, that could lead to a catastrophic failure, all available men rushed to the site of the break. Jordan recounts several of these breaks within the journal.

April 29, 1946

Superintendent Woods telephoned regarding a break thought to be below Avery’s tunnel. It turned out to be below the 2-mile tunnel. Forty feet of the canal had gone out, the site of an old landslide. The bank was lined at that point but seepage from below the canal undermined the support. Jordan and the men worked until dark and had to call it quits for lack of light.

Jordan went to Folsom to get lanterns. When he returned, none of the lanterns would work even though they all had new mantels. He stopped by Orangevale and Fair Oaks and told the districts to cut back on water as the ditch was out and would not be refilling the Baldwin or the Penstock reservoirs. They got the break fixed by 10 p.m. and turned the water back into the ditch. There were still leaks, so they had to turn the water out and continue repairs.

June 2, 1946

This was a serious break at Dead Horse Ravine. Journal entries from Jordan and his executive assistant Miss Link give a good overview of a typical emergency response required to fix the breaks and how it impacted the consumers.

Break near Dead Horse Ravine

Mr. Jordan: Sunday, about 4:30 P.M., Louie telephoned me from the Bar and said there was a break near Dead Horse Ravine. The telephone at the Dam was not working so he had to go to the Bar [Rattlesnake?] to reach me. Said about 40 feet went out. I told him to go ahead and start getting the lumber out and I would try to get the 4×6’s that he needs, from Auburn. Louie said that they had not been able to reach Woods by telephone.

Before I left town I telephone Mr. Fulton [Fair Oaks] and left word there that we had a bad break and that they would have to keep their pump running. Also reached Mr. Hull [Citrus Heights].

Went to Wood’s. Found that he was not there. Later learned that he had gone to the celebration in Folsom. Went to the Penstock and notified Gonzales. He had not had word of the break. Told him to hold them down if possible [reduce water deliveries to customers]; that it was a bad break. Gonzales went up the Canal to hold everything we were spilling at the Milk Ranch.

I sent Goff, the pipe man, to get the truck man. When I got back to the reservoir he was there. I telephoned Mr. Robie and finally reached him in Auburn. Told him that we badly needed some material and he said that he would get a man to open up and be there. I told him that the truck was on the way. After I had the lower end taken care of I went to Auburn. Got there about 8 o’clock. The truck man had not found the yard open but he got a communication to Mr. Robie and after some delay we got some material [lumber] which would substitute for what we needed. They had to saw part of it. The truck man got loaded and left about 8:30. I went to Woods place and from there we got word to Orangevale. Woods would start out in the morning to hold Rose Spring down to domestic [no irrigation.]

Monday, June 3, 1946

[Miss Link] Mr. Leslie phoned that the ditch tender had shut his water off this morning without a word while he was irrigating and in sight. Explained to him re the break and that all consumers must be limited to domestic.

Mr. Jordan: In the morning I telephone the employment office man about 5 o’clock. By agreement Dewey [Ball], the truck driver, was here a few minutes later. Found that the employment office was open but obtained men through the Agricultural Service. Got lunches for them.

I left my car at the top of the hill and we all went down in the truck. Got down there and found Martin. He reported all the material on hand. We got to the job and Louie had to work until midnight to get the material down. Got the men started. Decided to make a 7-foot flume. Found another weak spot a few hundred feet upstream. Told Martin to dig it all out and pour the crack so that would feel safe with it.

About 1 o’clock I came back with the truck man and we went to Woods’. Found that he did not have the additional grub yet. Finally got that in town and had to obtain more Coleman lanterns both at Folsom and Auburn. Sent the truck man back with those and the grub and a few other odd things we had forgotten.

Gonzales reported that they were taking the Penstock down. His gauge was 080. I telephone Fulton. He said we could pull him back a little more if we wanted to. We never did. Woods went to Rose Spring to cut them back more.

Later I went to the Penstock and through to the Baldwin Reservoir. Found that the reservoir was going down at the rate of more than a tenth an hour. While it had been full in the morning while we were getting the last of the water, it was now down six or seven tenths. At this rate we will be out of water in Rose Spring in another 24 hours. Decided we would not cut them any more at the Penstock.

I went home and reach Woods about 8 o’clock. He said he had no further word other than I had from Dewey saying that they would not need further men but would stay through.

Tuesday, June 4, 1946

[Miss Link] Mr. Woods reported that the repair work at the break was holding; that Louie put in a small head [of water] at 4 a.m. and a fairly good head about 6 a.m. The reservoir is at 387.8 and as the new water will reach the low end until tonight sometime, he is still holding the wholesale consumers down. They are drawing pretty heavy and at that rate the Brown Canal will be out of water in a couple of hours if he doesn’t continue to hold them down.

Mr. Jodan: Dewey telephoned about 5 a.m. Said they were back in town and had finished at the break. I came down town and gave most of the men something to get breakfast. They came to the office later for their checks.

It was 36 hours from the time the water went out until the time we put it back in, which is a pretty good record considering the length of the break and the fact that it happened on Sunday and we were really not able to get organized to be at work properly for 12 or 14 hours. However, it also shows that we cannot keep Rose Spring in domestic water more than about 36 hours after any break occurs. [Rose Spring was fed directly by the main canal and did not have reservoir buffer.] This is about the length of time that I reported to Mr. Stava [PUC] when I discussed the matter with him last winter.

Talked to Woods at noon. I told him to hold on to them until tomorrow morning. He said Orangevale is using very heavily. It is evident that Rose Spring will go out before the night is over. We should have water coming in from above about 1 or 2 o’clock in the morning. Of course it take another hour or two to get down the to the end of the Rose Spring pipe line.

July 16, 1946

Another break near the last failure had Jordan was on the scene until 5 a.m. When he left, his car broke down on Albright hill. He had the car towed to Auburn. They worked all the next day to build 24 feet of flume in 17.5 hours, which Jordan thought was a record. He left a little after midnight, only to have his car breakdown again.

Whenever a large break occurred, one of the tasks of Miss Link was to call the wholesalers to keep the water flow down. The fear was that the reservoirs would drop below the lip of the intake pipes to the districts and there would be no water for either domestic or irrigation use. Other major breaks demanding emergency responses were recorded August 9, 1946, May 25, 1947, June 23, 1947, and July 18, 1947.

Another danger was fire. On July 30, 1946, a major fire broke out on the Slade land and was burning toward the metal flumes above the Albright property (SW1/4, section 34, Township 12 North, Range 8 East.) The fire burned along the flumes but did not take them out. Jordan noted one telephone pole came down and a large amount of rock and branches fell into the canal. From that point on, the North Fork Ditch had problems with the telephone line it owned along the canal up to the dam.

Forgotten Places

When possible, Jordan would note the station or mile marker along the canal that he was referring to in the journal. In lieu of the specific distant markers, he would refer to local places, many of which were never listed on maps or have been forgotten. Some of the reference points Jordan used were the Kelly Ranch, Hector Ranch, Miller Ranch, Jamison Point Flume, Oklahomaville, Mansfield meadow, Dead Horse Ravine, Coyote Point, Coyote Bar, Miller cut, Mooney Lane Bridge, Wells Tract, Nixon flume, Wallace Shepard Place, the ’28 and ’32 canals, Panorama Point, the Old Prisser Place, and the cookhouse at Oregon Bar.

One bit of early California, that has not been confirmed, involved the Hector Ranch by Rattlesnake Bar. In late 1947, Mr. Hollingsworth went to the North Fork Ditch Co. offices regarding diversion by the ditch from the property. Hollingsworth reports that upon the death of the second Mr. Hector, the property reverted to the original heirs.

The property was originally owned by Von Muller Spatz, a German Chemist, who in the 1850s was a doctor for the mining community along the river. Spatz was his wife’s grandfather. Spatz became naturalized and changed his name to Miller. Hollingsworth said they were leasing the property to the Murch’s. NFD had been diverting water from Hector Ravine (aka Roseheimer Ravine) and the lessor would want it. Jordan said they only used the water for emergency purposes, and they would remove the 8” pipe if he wanted. Hollingsworth was going to start some gold mining on the property near the river before Folsom Dam was built covering the land in water.

Winter Projects

Jordan took the winter months, when water demand was low, to undertake projects on the system. In the first months of 1946, Jordan and Woods, superintendent of the North Fork Ditch, were replacing the water line into the Ashland area. The Ashland district was fed by Hinkle Reservoir and closely followed todays Auburn-Folsom Road down to the American River.

In August of 1946 Jordan surveyed the canal to determine where he needed to enlarge the ditch to carry more water. He estimated the cost to be approximately $20,000. The winter project began in November 1946. While Jordan was out on the ditch, attempting to get up a rain-soaked Albright Hill, the car slid off the road. He jacked up the car and it started rolling backwards until it hit a tree. This required another tow of the car up to Auburn for repairs.

The winter projects usually included the hiring of temporary men and setting up a camp along the work site. In early December of 1946, Jordan began assembling a camp at Oregon Bar by hiring a camp cook, getting tents, coffee pots, and setting up hot water system for showers. He got men from the employment office and the pay was $0.80 to $1.25 per hour. Jordan noted that he would deduct $1.50 for board.

The first part of the winter of ‘’47 project was to replace the flume along the Albright Ranch. Next, they moved to widening the ditch around Oregon Bar. This required the blasting of rock as they needed to widen the ditch by 12 inches. On January 21st, Louie called and said the camp cook quit. It was typical for several of the temporary workers to quit and Jordan was always stopping by the employment office to get new recruits.

A sign that the United States was slowly moving to normalcy after World War II, Jordan notes he was able to secure a sugar ration check 246 pounds of sugar that he took to the camp at Oregon Bar. The widening project was finished by March 7th, but Jordan noted the new ditch leaked like a sieve. He had them take the water out of the ditch and reline parts of the canal.

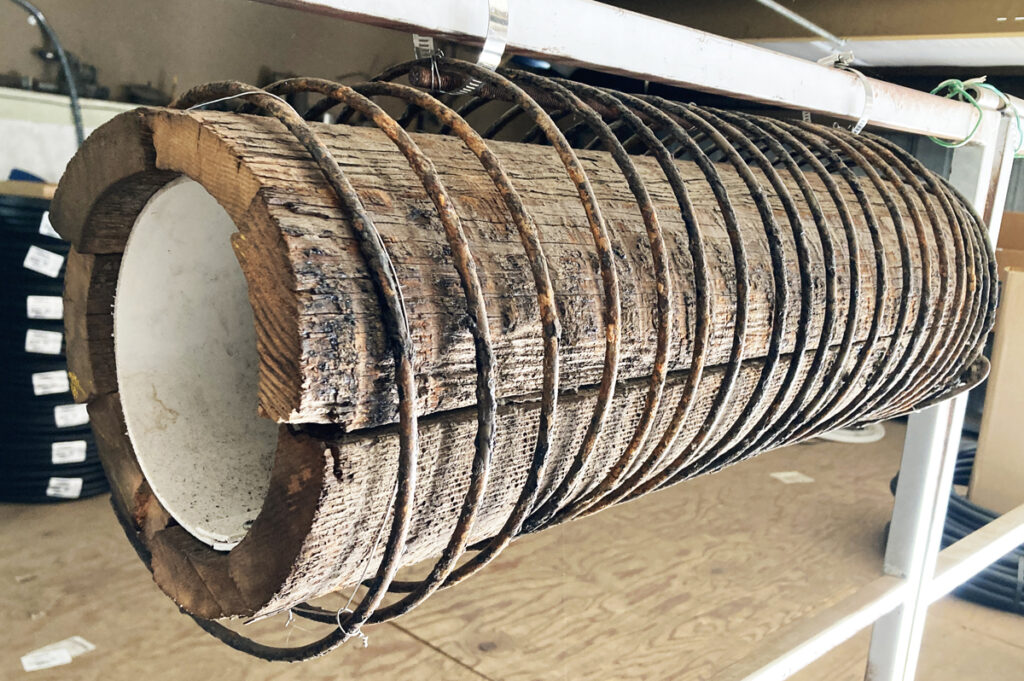

The following winter beginning in November 1947, would tackle installing new steel pipelines to Cardwell Colony, San Juanita Colony, and replacing a wood stave pipe that serviced the Orangevale Water Company. The camp was set up at Hinkle reservoir for the crew. The old wood stave pipe blew up from the water pressure once they uncovered it.

By December 1st they had gotten the Orangevale bypass line in and all that was needed was some welding and to fill some of the joints with lead along Buddecke’s property. The next project was the 16-inch steel pipe for the Cardwell Colony. The only major disaster was that the camp cook tent caught fire and burned down. Jordan had to Carnies to get a new tent.

Weather

The journal usually begins with the weather. It was noted by either Miss Link or Jordan the weather conditions including temperature, wind, fog, or rain. Rainfall was carefully noted. Even though the North Fork Ditch had a couple of reservoirs, that water supply would only serve the customers for one to four days depending on the demand. It was almost a direct feed from the American River to the consumers. If the river dropped, it was almost like having a ditch break, water would have to be rationed.

Jordan had noted that 1947 was starting off very dry with little rainfall. He decided to meet with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers about potential emergency water releases from the North Fork Debris Dam. He also wrote to the California Debris Commission requesting releases and asked how much the water would cost the North Fork Ditch Co.

Legal

Jordan was also the point person for legal matters. In January of 1947 he had to work on a dispute with Peter Dickinson on an old right-of-way agreement. The water canal cut through the Dickinson’s property (eastern tip of Mooney Ridge by Rock Springs) and the North Fork Ditch had a bridge over the canal and water gauge at that spot.

It was also part of Jordan’s job to write up protests to any potential diversion of water from the river or a creek flowing into the river. The Maxwell-Christy Lumber Co. had applied to divert water that would normally flow into the river for part of their lumber operation. Jordan met with Maxwell on July 23, 1947 and informed him that even though the diversion was small, a number of small diversions over a period of time will make a large one.

Maintenance

Outside of major breaks and winter projects, it was basic maintenance on the canal, reservoirs, and distribution system that monopolized most of the time of the small crew of men who work on the North Fork Ditch. There was a core group of men that responded to maintenance issues along the canal. James Woods was the Superintendent and primarily worked in the retail service area.

In the late 1890s, the North Fork Ditch started supplying water to more retail consumers for domestic and irrigation purposes. The main piping system was primarily wood stave pipe. By the 1940s, the wood stave pipe had exceeded its useful life. Consequently, the journal shows that it was a constant struggle to identify leaking pipes, make repairs, and transition to steel pipe that had different outside diameter.

There are weeks within the journal when Jordan notes that Woods is hopping from one leak or blow out to another. Most of the pipe failures were occurring in the Cardwell Colony, San Juanita Colony, and down the Ashland line. Just a sampling of the maintenance issues the North Fork Ditch crew had contend with were:

- Dickinson bridge falling into the water canal, no lumber in Folsom to repair it

- Blow out on the Wells Tract next to Greenhalgh place in Orangevale

- Dead Cow in the canal on the Pace-Schwerdtle line.

- Small landslide into the ditch at the 10-mile mark on the main canal

- Leak on the Cardwell line and the water is flooding a shed owned by Mr. Mansfield

- Leak on the main canal at 3-mile stake above the old Avery cabin

- Road grader hits wood stave pipe outlet that serves San Juanita Colony and Fair Oaks.

- Penstock pipe to Fair Oaks had dollar size hole. Woods tries to repair it and the whole pipe crumbles apart

- Low river flow in August 1947 reveals holes in the face of the dam

- The old Kelly Ranch waterwheels are falling apart and blocking flow in the main canal

- Cattle truck breaks through the bridge at the Hector Ranch, all four cows and one horse walk away unhurt

- Mrs. Schaw’s cattle keep breaking down the fence around Baldwin Reservoir

- Mrs. Hinkle’s cattle keep breaking down the fence around Hinkle Reservoir

In early 1946, Jordan notes how he was contracting with Folsom Prison for men who were at the County Road Camp. The road camp, if accurate, was located on Baldwin Dam Road, south of Oak Avenue. Jordan was not impressed with the work performed, but it was low-cost labor. Jordan used the prisoners to clear brush and dig some of the trenches for new pipe installations. However, restrictions on when and where they could work limited their use. Jordan was told the prisoners could not work in Placer County. Jordan did not rely on the prison labor in 1947.

C.W. Clarke Co. Board of Directors

Jordan was in regular communication with the C.W. Clarke Co. that owned the North Fork Ditch Co. The Board of Directors met in San Francisco and Jordan would frequently travel to the Bay Area to give updates on the North Fork Ditch Co., explain problems they were having, and ask for money. Jordan recorded in the journal for February 28, 1946:

I reported on money on hand and gave them a resume of the figures. It would indicate that we could maybe just about “skin” through by holding payment of some bills. Then I reported that I had finished with the shovel at the new high line canal but that I did not raise the banks of the Brown canal.

Gave them a verbal report on the Dickinson vs. N.F. D. Co quiet title suit.

Told them re difficulties of camp: that I wanted them to join with me re a selection for a permanent camp before fall, since we will have to have some permanent camp if we are going to continue to hire men.

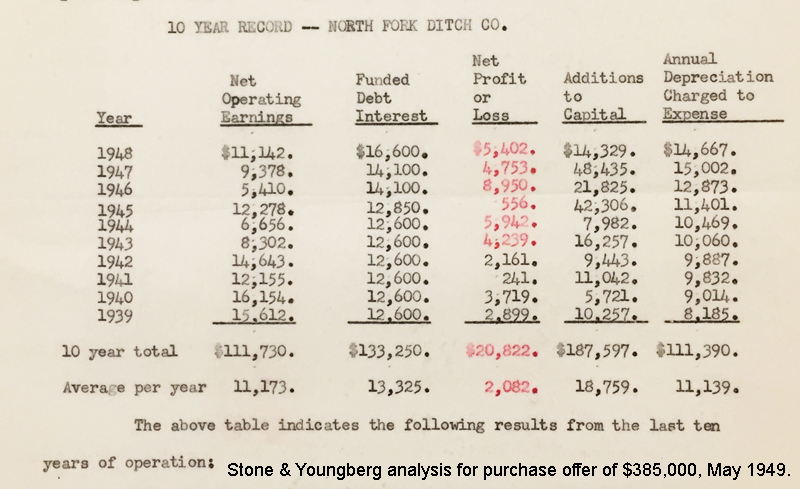

The North Fork Ditch Co. rarely made any money. From a financial analysis prepared for a prospective sale of the North Fork Ditch Co., the company had a net loss of $20,822 over a 10-year period from 1939 to 1948. At the July 11, 1946, Board meeting, Jordan suggests that the C.W. Clarke Co. investigate if the company could gain any tax advantage if the North Fork Ditch Co. should default on its loans.

It was not idle speculation about the precarious financial condition of the North Fork Ditch Co. Jordan tells the Board the North Fork Ditch has run out of cash. The Board tells Jordan they don’t want to put any more money into the ditch. The Board would prefer to sell the ditch. Jordan writes in the journal,

I told them that there had not been at any time in my 20 years dealing with them that I had not been willing, at a moments notice to do everything possible to sell the North Fork Ditch Co. That I was sorry if I had done anything to create the impression that I would not everything to help such a sale. That I would expect the compensation to me, in the event of a sale, to be as originally agreed upon. They said they expected to hold that agreement. C. W. Clarke Co expressed themselves as expecting in any event, no matter what might happen in the North Fork Ditch Co., to keep me with them.

No sale was imminent, but the need for cash was necessary. At the October 2, 1946, Board meeting, it was agreed to loan the North Fork Ditch Co. $50,000. Jordan was also informed that Stone and Youngberg, an investment security broker in San Francisco, would be contacting him about appraising the ditch and begin working to find a buyer for the North Fork Ditch Co.

The North Fork Ditch Co. invoiced the retailers and wholesalers twice a year. In June of 1946, the Board approved a motion to allow Jordan to file for a rate increase with California Public Utilities Commission. The Public Utilities Commission approved a smaller increase than Jordan had applied for. Nonetheless, Citrus Heights and Fair Oaks irrigation districts protested the rate increase. Instead of paying the higher rate to the North Fork Ditch Co., they deposited the money with the Public Utilities Commission until a hearing on their protest could be heard.

NFD Sale

The rate increase protest notwithstanding, several of the irrigation districts were interested in purchasing the North Fork Ditch. Jordan attended a joint meeting on April 20, 1947, where representatives of the Citrus Heights, Fair Oaks, and Orangevale districts were present to discuss paths to purchase the North Fork Ditch. Jordan wrote that there was not a lot of enthusiasm for buying the water system.

Earlier in 1946, Jordan noted that the Fair Oaks Irrigation seemed to be in turmoil with employees threatening to quit over not being paid. He talked to one Fair Oaks district director who said the district was broke. There was talk of putting restrictors on the water connections to reduce usage by customers. However, it would require the district to pay an hourly wage of $1 an hour and they could not afford it.

Jordan had a good relationship with the districts that bought water from the North Fork Ditch. He routinely talked with Howard Greenhalgh of the Orangevale water district. After the joint meeting of district, Jordan talked with Greenhalgh who said the board of the Orangevale water district was not interested in purchasing the North Fork Ditch.

Greenhalgh said the other board members wanted to stay away from bonding their property to secure a loan. Greenhalgh was receptive to the proposition of the Orangevale water district participating in a purchase of North Fork Ditch with the other districts. Jordan wrote of the discussion, “Of course, all of his Board are all old men and it may be hard for him to get them to see it his way.”

Jordan was not opposed to selling the water system. It is apparent from his language in the journal that he doesn’t think the North Fork Ditch can keep hobbling along under the ownership of the C.W. Clarke Co. The Clarke company did not want to put any more money into the ditch and Jordan needed more money to keep the system operational.

At a May 1947 Clarke company meeting, the broker told the directors that they needed to reduce the asking price of the North Fork Ditch down to $330k or $380k. The asking price was based on the profit—loss statement where the North Fork Ditch lost more money than it made. Jordan argued against lowering the asking price. Mrs. Brown, one of the directors, was in favor of lowering the asking price.

Folsom Dam

The speculation over a proposed Folsom Dam complicated any sale of the North Fork Ditch. While Jordan did not come out and put it in the journal, it seems as if he saw a Folsom Dam project as solving many of the financial problems at the company. On March 22, 1946, Miss Link writes, “Completed the budget and the report. Our finances are not very encouraging.”

That same day Jordan phoned the North Fork Ditch Co. accountant and reported, “Phoned Mr. Seymour [accountant] and decided to let the Folsom Dam matter rest for the time being as it is evident from the newspaper article of a few days ago that construction of the dam will not begin immediately. Told him, however, that there is a very important matter which should be discussed. Our outgo is larger than our income and something must be done. Asked Mr. Seymour to sound out the Railroad commission [PUC] engineers on next Monday while he is in S.F.”

If an imminent acquisition of North Fork Ditch facilities by the federal government was not going to happen, perhaps the Public Utilities Commission would grant them a rate increase. Previous discussions with Mr. Seymour focused on how much the North Fork Ditch Co. might be compensated by the federal government for the loss of part of their water system and reservoirs if Folsom Dam was constructed.

The first concept of the Folsom Dam was for a flood control structure impounding much less water. The small dam would have left much of the main canal intact but impact the canal and Hinkle reservoir near the end of the line.

The second iteration of Folsom Dam included flood control, power generation, and irrigation water for the Central Valley Project. The much larger Folsom reservoir would completely swamp the main water canal all the way up to Rattlesnake Bar. In 1946, no one knew how Folsom Dam would change the landscape and North Fork Ditch Co. water system. Because so much was unknown about Folsom Dam, Jordan had to focus on the immediate concern: the North Fork Ditch was running out of operating capital.

In April 1946, Jordan tells the Fair Oaks irrigation district they are just waiting until the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers decides on the height of the dam. In May, Jordan visited Mr. Roberts of the Army Corps and Roberts relates they were absolutely committed to a high level dam if they can get the congressional approval. The larger Folsom Dam concept would take out Hinkle Reservoir. Mr. Roberts said they would build a new reservoir for the North Fork Ditch. However, Roberts would not commit to financial considerations as that all had to go through the real estate division.

The following year the Folsom Dam project was closer to getting approved by congress. In September, Roberts leaves notice for Jordan that U.S. Army Corps of Engineers would be roaming around the proposed Folsom reservoir area. Roberts wanted Jordan to know of their activities because their presence always created gossip and misinformation from the residents. In October 1947, Jordan visited Roberts to get assurances that any supplied water flow from Folsom Dam would accommodate the higher 35 cubic feet per second diversion the North Fork Ditch had been granted from the river. Jordan also wanted to reiterate that they needed some sort of service connection for the Ashland district as Hinkle reservoir, that supplied the area, would be wiped out by the right wing dam of Folsom Dam.

Public Utilities Commission

In the journal, Jordan alternates between referencing the Railroad Commission and the Public Utilities Commission (PUC.) In 1946, the Railroad Commission became the Public Utilities Commission, a title better suited to its mission as the Public Utilities Commission reviewed a growing number of public utilities, like the North Fork Ditch. Jordan probably spent more time communicating with the PUC than the C.W. Clarke Co. Board of Directors.

The PUC needed a clear financial picture of the North Fork Ditch in order to approve any rate increases. In March of 1946, Jordan stops by the PUC in San Francisco to update Mr. Stava of the PUC of the state of the North Fork Ditch. Jordan writes, I went to the Railroad Commission and took my budget showing the figures. Showed them to Mr. Stava. Showed him how I was keeping from default now but it was impossible to keep from doing it in September or October. But, that I had finished my winter work and put in my improvements. Had cleaned the Penstock without shutting off water; put in the improvements for the domestic service in Rose Spring. The Canal has been cleaned and we are in better shape now to begin the season than we have been for some time.

I went over the amount we are paying each man with him. I was running with less men on a payroll of eleven thousand dollars now than in the old days when I had only about six or seven thousand for the same period. My monthly wages to each man indicated to his mind that I am not paying anything but comparatively low salaries; that there is not any particular retrenchment that I can make that will help at all.

When drafting the 1946 water rate increase application, Jordan contemplates changing how the water is invoice for from inches to cubic feet or acre feet measurements. He also decides to add some cost estimates to the impending chlorination facilities that Sacramento County had been requesting. When Jordan meets with Mr. Stava of the PUC, Jordan tells him they might have start charging for connections for new consumers. Stava tells Jordan that it would not be allowed because the PUC considered those expenditures in the capital account and the North Fork Ditch Co. and was allowed a return on that sort of investment.

In 1947, Jordan would consult with the PUC on how they viewed the $50,000 loan from the C.W. Clarke Co. for flume replacements and capital improvements. Jordan would also have to fight with the PUC to release the water payments from the Fair Oaks and Citrus Heights irrigation districts. The districts, in protest of the 1947 water rate increase, submitted their payments to the PUC until the issue could be resolved. However, Jordan desperately needed the money to pay employees, vendors, and contractors working on the water system.

C.W. Clarke Co Land Agent

Jordan was not only the General Manager of the North Fork Ditch Company, he was also the land agent for the C.W. Clarke Company for properties they owned in Fair Oaks and the Delta. The Clarke company was interested selling land they owned in Fair Oaks and in the Delta. Jordan reported that he was able to sell 15 acres of land in Fair Oaks to the flying club in April of 1946.

The C.W. Clarke Co. owned land on Woodward Island in the Delta. It was Jordan’s job to negotiate with a Chinese man who wanted to purchase the property. Jordan mentioned the Chinese man was hesitating because a tong war might break out, in which case, the man would have to travel to Sacramento. Jordan also had to work with some of the reclamation districts on the island regarding the installation of new pumps for the island drainage.

On several occasions, Jordan travels down to Paso Robles where Mr. Clarke lived. Jordan was taking an inventory of the cattle Clarke owned for the company. It was never mentioned if Jordan’s wife ever accompanied on his trips to Paso Robles or San Francisco. It was noted that Jordan and family took a vacation to Idaho. They would also travel down to Stanford to watch football games and over to Santa Rosa where his son Loring K. Jordan, Jr. lived.

Retail Consumers

Miss Link was usually the first contact for retail consumers to voice a complaint or request service. It was Jordan who performed the field work like collections. Jordan stopped by the Hide-De-Ho bar several times in 1947 to find Mrs. Murray over her delinquent bill. It was unclear whether Mrs. Murray was the owner of the bar or just a frequent patron. He finally caught up with her and she paid the bill. Jordan then instructed Woods to turn the water back on at Mrs. Murray’s tenant’s house.

Mr. Buddecke complained to Woods that water was running down the hill from one of the reservoir on to his property. Jordon instructed Woods to tell Mr. Buddecke they had been cleaning the reservoir for 45 years and the water always runs downhill. That as far as Jordan could ascertain, it was doing Buddecke’s property more good than harm.

When Woods was not available to trouble shoot a problem, Jordan would visit the retail customer. In May of 1947, Jordan met with Mr. Atkins who complained he was not getting the full 3 inches of water he was paying for from the irrigation connection. After doing a preliminary elevation survey, Jordan agreed. There was at least a 12 foot difference in elevation between the line and Atkin’s outlet, sufficient to provide the 3 inches of water. Jordan determined that Woods would have to open the line and see if it was clogged with rocks or tree roots.

Mr. Lambert called the North Fork Ditch office to complain about the excessive water bill. Miss Link informed Mr. Lambert that the $7.50 covers the winter domestic service, which was not previously billed to customers in the Rose Spring District. The domestic service was for piped water into the house and separate from the irrigation service.

After a canal break on July 17, 1946, Mr. Lambert called Miss Link again wondering what happened to the water. She explained it was bad break in the canal that took several days to repair. Mr. Lambert informed her that he lost about 200 gladioli blooms, quite a financial loss. Miss Link informed Jordan that, “Mr. Sakata, one of our Japanese consumers who has returned from the Concentration Camp, came in and introduced his son whom he said would be in charge of the ranch.”

Jordan writes that Woods told him that Mrs. Foley would stop by and pay the water bill. Jordan tells Woods to go to her place every day until she paid the bill. He added, “We don’t care about a sale. We want out money.” Jordan’s attitude was a direct reflection of the financial stress the North Fork Ditch was operating under in 1947.

In late 1947, Mrs. Butler stopped by the office to discontinue domestic service, but would keep the irrigation line service. Her reason was that most of the time there was no water to the house and when they did get water it was dirty. Mrs. Butler decided they would use the spring on their property for domestic water.

Mr. Dahm went to the North Fork Ditch office and complained his water was shut off without notice. Miss Link explained he had not paid his second 1946 installment. She told Mr. Dahm that he could deposit the money with the PUC and file a dispute with the PUC that he had paid the water bill. For all the customers that disputed bills or wanted to discontinued service, it seems there were twice as many people who wanted new service.

The new service requests in the retail service area represented the post WWII population growth in south Placer and northeastern Sacramento counties. If Jordan saw the trend of increasing water demand occurring in 1946 and 1947, he did not write about it. It was clear from the journal entries that more people were moving into the area and wanted water for domestic and irrigation purposes.

Mr. A.R. Willhite purchased 25 acres from Mr. Foley, known as the Old Scott Ranch, and wanted water. Jordan advises taking water from the line on Columbia Avenue, known as the Foley lateral. However, Willhite would have to put the pipe in himself. Mr. A.F. Bertinoia wanted water for 10 acres he bought from Mr. Eckerman off of Columbia Avenue. Mrs. Byers wanted service for lot 44 of the Cardwell Colony.

Peter Dickinson wanted another ½ inch of water. Jordan writes that North Fork Ditch employee Myron Bruno said the water box was not in good shape and Dickinson would need a new one to get the extra water through the connection. In a very unfortunate 1952 event, Peter Dickinson would be shot by his daughter Etta Mae at their property. Etta Mae had a mental break down over declining the offer from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to purchase the ranch as it was to be flooded by Folsom Lake.

Mr. Eckermann informed Jordan in May of 1946 that he was thinking of buying the old Douglas place with George Spahn. They would split the property and Spahn wanted service on the westside. Jordan is informed of new homes in the Orangevale Bluffs subdivision. Jordan suggests to contact the builder to see if the Orangevale irrigation district can supply the water. For the North Fork Ditch to supply the water, they would have to tap into the water line that ran to Fair Oaks.

There were times when the North Fork Ditch could supply the water but could not front the cost to install the pipe to the new customers. When this occurred, they would offer to credit the customer the cost of the pipe installation over a 10-year period.

There were several property owners of the Inwood Colony that wanted water service. The Inwood Colony, west of Auburn-Folsom Road, was originally established by Isaac Hinkle who worked for the North Fork Ditch for over 40 years. Isaac Hinkle had been the superintendent until he retired. Hinkle had purchased property that would be bought from him and turned it into the Hinkle Reservoir. He died in 1933, but the Inwood Colony subdivision lived on.

On September 10, 1947, Jordan noted he was at the Sacramento County Assessor’s office reviewing the Inwood Colony lots to determine a new service line. In October, Jordan was out surveying the area to find the best pipeline route. Jordan told one of the property owners, Mr. Walker, requesting water service, that he did not like line, but could not find a route that was superior. At the end of December, Jordan writes that they used the tractor to break up the old railroad grade to cut a trench across the road. The railroad grade was from the Sacramento, Placer, and Nevada Railroad that ran from 1862 to 1864.

Wholesalers

There were similar demand increases on the wholesale side. In 1946, Fair Oaks wanted to increase water purchases from 700 to 750 inches. Mr. Wahrhaftig of the Orangevale irrigation district told Jordan they would increase their water deliveries by another 15 to 20 inches. Jordan writes on April 4, 1946 that he informed Wahrhaftig that he was accepting the application for 500 inches of water for the Orangevale irrigation district and do everything he could deliver the water.

On April 10th, Mr. Fulton of the Fair Oaks irrigation district tells Jordan they have installed new pumps and wanted to increase the purchase to 750 inches. Jordan tells Fair Oaks he is not sure if he can deliver the full amount, especially if the North Fork Ditch got into a bad spot, like a canal break. On April 14th, the Fair Oaks line failed near the Lincoln cut, this would have been near Orangevale Avenue and Gold Creek. Woods got the break fixed.

Jordan was presented with another problem on March 20, 1947. He learns that Sacramento County wanted to widen and lower Greenback Lane where the road approached Gold Creek, west of American River Canyon Drive. The North Fork Ditch pipeline to Fair Oaks crossed at the point where the county wanted to lower the road. Jordan knew they had to lower the fragile pipeline because it was going to get hit by the road crew lowering the grade.

Jordan had good relationships with the wholesalers. He worked well with most of the superintendents of the irrigation districts. At each of transitions from a North Fork Ditch supply to the wholesaler’s pipeline was a water meter. Either Woods or Jordan would inspect the water meters to make sure they were recording the proper flow. In May of 1946, they found that the Citrus Heights manometer was not functioning properly. The meter was only showing 200 inches of flow and Jordan knew the flow was double that amount.

Woods and Jordan broke down the manometers, cleaned them, and replaced the gaskets and tubing. In July 1946, the water meters were back in shape with Fair Oaks reading 700 inches, Orangevale at 400 inches, and Citrus Heights showing a flow of 420 inches.

There was a sense of frustration when dealing with Mr. Hull, the Citrus Heights superintendent. Jordan showed Hull how he could regulate the system’s winter pressure by utilizing a 4” by-pass valved installed. Hull told Jordan he would start using it. On several occasions, Jordan stopped by to learn why Citrus Heights was using so much water during the months. Hull admitted that he was not given the approval to reduce the pressure and flow.

Water Quality

As testing methods improved, health departments were able to accurately detect more contaminants in water. In April of 1946, the Sacramento County Health Department phoned and told Jordan that water samples taken at Sylvan and San Juan schools were contaminated. Melvin Olsen of the Health Department confirms that e. coli was found in the water samples.

Jordan has Woods check for water coming into the canal from creek overflow. There was some drainage coming into the canal at the Hector Ranch where they had pipe to capture runoff water in the ravine. Jordan drives Olsen around to schools in Fair Oaks and Orangevale to take more water samples. Some of those samples showed contamination also. Olsen said the contamination could be from the pipe itself. Since there were lots of wood stave pipes used throughout all the districts, the contamination might be coming from anywhere in the system.

Jordan talks to the Fair Oaks irrigation district about the contamination. He estimates that it would cost about $2 per inch of water with chloirne to reduce or eliminate the contamination. In May, water samples from the main canal showed no contamination. Regardless, Jordan begins gathering information about treatment costs.

A year later in 1947, Jordan addresses the issue of chlorination with the wholesalers. This was prompted by a letter from the State Board of Public Health regarding treating surface water. However, the wholesalers showed little interest in adding the additional cost to their water bills. Because the retail water had not been tested or found to be contaminated, Jordan did not review treating the retail side of the water system.

While invisible contaminants were a concern, visibility dirty water garnered more consumer complaints. In June of 1947, Jordan noticed cloudy water coming down the river and into the main water canal. Jordan would spend the next few weeks driving up the North and Middle Forks of the American River looking for the source of the cloudy water. He suspected someone either had a gold or gravel mining operation working on the river.

Jordan drove by the Mountain Quarries gravel operation, but they were not working by the river. He stopped by Auburn to see if Mr. Robie was operating his gravel pit potentially causing the discolored water. In late June, Jordan found a doodle bug at Spanish Dry Diggins on the Middle Fork that appeared to be part of the Wiltsee operation.

A doodle bug was a barge floating in the middle of the river. A crane with a bucket would scoop up dirt from the riverbank and dump it into a hopper on the doodle bug. River water was used to wash the dirt separating out any gold. A temporary rock dam was built across the river to create a pond for the doodle bug to float on.

A couple of days later, Jordan was able drive part way down to Spanish Dry Diggins. He learned Wiltsee had two drag lines, but they were not in operation. Jordan drove up to Volcano and then down to the Horse Shoe Bar Mines, below present day Oxbow Reservoir. He talked to Mr. Gerke, superintendent of the mining operation. They were mining the lower end of the riverbanks. Gerke told him he could put in a second dam to help clean up the water. Gerke was not sure how much gold they would recover until they cleaned-up after July 4th.

Employees

Some of the employee’s that Jordan routinely referenced were Myron Bigley, Jr, Loomis, Louis Bruno, Newcastle, George Goff, Folsom, Charles O’Keefe, Loomis, James Woods, Superintendent, Folsom, and Josephine Link, Sacramento. Several of the employees lived in structures owned by the North Fork Ditch such as Gonzales and Martin.

While there were many loyal employees of the North Fork Ditch, they did not all perform their duties to Jordan’s expectations or instructions. On March 21, 1946, Bruno informed Jordan that he had run O’Keefe out of the winter work camp because he had been drunk and had been disturbing the men for several days. O’Keefe would later ask to be rehired and Jordan agreed as long as he did not cause any more disturbances.

Edward Stanley, also known as Shortie, would go missing for days. Louie reported to Jordan in January 1947, “Shortie was on a drunk and had not been there for several days. I [Jordan] told him to send somebody out to flag him down.” Jordan instructs Miss Link to call the employment office to find a pipe helper for one of the installation jobs. He also wanted the employment office to keep the North Fork Ditch in mind for a truck driver because, as Jordan put it, “….Dewey Ball may blow up any time.”

When he could, Jordan would allow the men to stay in one of the cabins along the ditch they owned. One hire quit because he did not think the old Prisser place was adequate. But another hire said the old Prisser place was great and he would bale his own water until Jordan got the water tank fixed. In October 1947, writing about strategically placing employees along the ditch, Jordan notes, “Louie is to be away next week. Made arrangements to have Brown move down to the Prisser place,….Gonzales to move back to the Hinkle Reservoir. Shortie is still off. Whether he is still sick and drunk too we do not know.”

On several occasions Jordan granted a leave of absence for men who sick and needed to be hospitalized or had to take care of a sick child. In one instance he gave one of his employee’s a short term loan to cover the time he was off work. A continuing problem was the low pay Jordan was forced to offer. In April of 1946, Jordan phoned Mr. Laufenberg of the C.W. Clarke Co. Board of Directors and wrote, “Phoned Mr. Laufenberg in the morning that it is impossible for me to obtain a new pipe man and a truck driver at the wages we have been paying; that if I did pay more for those jobs, it meant that I would have to increase everybody right down the line. Walter told me to go ahead and pay whatever I had to pay, even if that meant to increase them all the way down the line.”

The low pay led some men to leave for better pay. Mr. Bigley had been off work for a week with various excuses given to Jordan. Jordan stopped by his house to learn what the issue was and wrote, “I went to Bigley’s and found out that he had gone to work for the P.G. & E. That is the first time they have intimated that he is going to work for someone else. Obviously, his wife is not telling the truth re when he took his physical examination and they have been afraid to tell us the truth. I saw Woods later and told him that I would go back to Sacramento and do my utmost to get a truck driver and pipe man out; that we would not try to haul the lumber ourselves since Louie cannot drive a truck. We must hire the right man to do it. Woods reported another leak in Cardwell. That is five days he has had to work on that line.”

Another employee, Gonzales, complained about the low pay. Jordan negotiates $0.80 per hour and the North Fork Ditch Co. would pay for the gas for his car. Gonzales would continue to complain to Woods about the pay, but Jordan tells Woods he is not budging on the hourly rate or the gas allowance.

Then there were times when the employee’s just did not follow Jordan’s instructions. Jordan writes, “I went to the Penstock and found that they had put the bridge in the wrong place and built it of the wrong material. Obviously it is Woods’ fault. It is not satisfactory but decided to let it go. It will probably do where it is.”

Loring Kenneth Jordan

Loring K. Jordan was born on November 1, 1888, in St. Joseph, Missouri. He graduated high school in 1906 and moved to New Haven, Connecticut, where he studied civil engineering. When Jordan was 21 and at Yale, he suffered stroke that paralyzed the left side of his body. He would recover and graduate in 1909.

By 1914, Jordan was living in California. He married Grace Hoover on December 25, 1914, in Templeton, CA, just south of Paso Robles. In 1917 the couple had moved to Shasta County where Jordan was a civil hydraulic engineer for the Anderson-Cottonwood Irrigation District. His WWI draft registration card lists his physical characteristics as slender, medium height, brown hair, and blue eyes.

Jordan and Grace moved to Colusa, CA, and in 1920 they had two children, Loring, Jr. age 4 and Nina age 2. Jordan was employed as civil engineer for an irrigation company, and he would buy an orchard in Colusa. Isaac Hinkle had been the General Manager of the North Fork Ditch until it became clear that a higher level of engineering skill was necessary to keep the ditch operating. George Nickerson was made General Manager with the main office at the Forum Building in Sacramento.

When Nickerson died, Jordan was hired as the General Manager and moved to Sacramento from Colusa in 1927. Jordan would continue to work out of the Forum Building routinely traveling from Sacramento up to the North Fork Ditch most weeks. In 1954, voters approved the San Juan Suburban Water District that bought the North Fork Ditch Co. for $620,000. While Folsom Lake would make the main water obsolete, the new water district acquired the water rights of 30,000-acre feet established by the North Fork Ditch.

Jordan would remain at the new district during the transition from private utility to special district. Loring Jordan retired and lived in Sacramento until he died in 1966. Jordan’s name is on several maps related to the North Fork Ditch, reservoirs, and distribution system. He performed many surveys of the ditch when it was necessary to change the main ditch line or to add a new water canal or pipeline.

Hydraulics of the North Fork Ditch

Perhaps nothing was as impressive in the two-year journal than Jordan’s management of the gravity fed water system. The only pressure on the water to push it through the various water canals, reservoirs, and pipes was the change of elevation. When the water demand was highest in the summer months, Jordan was constantly checking the ditch and reservoir levels. He only had a 36-hour supply of water in the reservoirs to supply the entire water system during peak demand.

Jordan had an intimate knowledge of the water system. There were several variables that Jordan had to consider when balancing the system such as weather, leaks, customers pumping from the ditch, and how much water they could spill at the reservoirs. He was always making calculations in his head about the flow such as his entry from June 17, 1946.

I went to the Orangevale meter house, they were not drawing quite 400 inches. I thought they would be drawing more than that.

From there I went to the reservoir. Met Louie and Jim. Louie reported the dam gauge at 2.96. I told him I would let him know by night as to how much more I wanted him to raise.

Gonzales came and I followed him to the Penstock. There is only a small amount [spilling] at the Penstock and about 50” spilling at the Hinkle Reservoir. The Baldwin Reservoir is above the high water mark. I told him to reduce it; to spill at the Penstock; that I was going the raise the canal.

Louie telephoned later and I told him to raise .01 a day and hold it to 2.98 until we see what the weather is. It will probably continue warm.

I estimate that Orangevale, Citrus Heights and Fair Oaks will draw at least 2 sec. feet and if Mrs. Schaw [pumping from the main canal] draws 2 that will be 4. So we will have to get the Canal up in the next two weeks. Louie reported 3” free board at the Schwerdtle waste gate. That Martin had all the damp spots on his beat and could probably stand a 3-inche rise.

Jordan never mentions that he is getting any reports about the flow of the river. Normally, there was sufficient river flow from snowmelt in the summer to keep water moving through the head gates at the dam. However, 1947 started off dry. Jordan noted that by February 27, Sacramento had only 7.71 inches of rain, normal would be 12.95 inches. Snow depth at Norden was 31 inches when 94 inches of snow was normal for that time of year.

By May 4, 1947, Jordan reported that the wholesalers were starting to draw heavily on the water system. Jordan instructs Louie to keep raising the flow from 2.90 at the dam by .05 per day until they are over 3.00 at the head gates. On the lower end of the ditch at the Dickinson gauge the reading is 2.40. Jordan wants it at 2.65.

Jordan stops by Baldwin Reservoir and Gonzales has the level at over 3.90. Jordon admonishes Gonzales to never let Baldwin get over 3.90 as they are not approved for a water height any higher. Jordan then goes to Hinkle Reservoir and releases an additional 2 inches of water to lower Baldwin. On May 14, the Dickinson gauge is up to 2.60 and they are spilling 150 inches at Hinkle and another 30 inches at the sand trap on the ’28 canal.

On May 15, Jordan learns the Fair Oaks is drawing 750 inches, Citrus Heights was at 575 inches, and Orangevale was up. He thinks that is the heaviest draw he has ever seen by the wholesalers so early in the year. Normally, they don’t demand that much water until July 1. My mid-June, the dam gauge is at 3.14, but only 270 at Dickinson. Jordan believes there must be some large water losses that are not visible somewhere along the line between the dam and the Dickinson gauge.

Because the ditch is not raising to the level Jordan wants, he instructs Louie to close the fish ladder at the dam. He tells all the men working along the canal to look for any leaks and to begin closing off the sand traps. Earlier in the year, Jordan applied for emergency releases from the North Fork Debris Dam at lake Clementine. The Debris Commission accepts his bid of $1 per acre foot for releases from the dam.

Alarm bells started going off for Jordan when, on July 10, 1947, the Dickinson gauge is at 2.60 after weeks of raising the flow into the canal. He tells Louie to raise the water level at the head gate to 3.26. Louie does not think the flume below Oregon will handle the higher flow and will spill over. The river is fluctuating in flow between night and day making it more difficult to determine how much water to put into the canal.

On July 11, the Dickinson gauge is down to 2.55. The head gate gauge is steady at 3.26. Jordan instructs Louie to raise the pond behind the dam by placing sandbags across the top. By the afternoon, the Dickinson gauge has dropped to 2.50. Jordan cannot figure out where the losses in the system are occurring.

Jordan travels the main ditch on July 12th. He heads down the Nixon Road and sees a little leakage on both the lined and unlined portions of the canal. On the lower on the canal, Jordan notes that the ravines on the Mooney place are dry, no leaks. In the Rose Springs District around the Rodgers place all of the ravines are dry and Jordan does not think he has ever seen the landscape so dry at that time of year.

By July 18, Jordan notes they will have to work on the tunnel right below the dam, it needs more concrete for the transition as it is deteriorating. The fish ladder at the dam has been blocked from spilling water. Jordan figures he may not need the emergency releases from the debris dam if everything stabilizes. The flow over the dam on August 2nd, is equal to about half the flow going into the ditch.

The small amount of water spilling over the main dam below Auburn, reveals holes or missing rock in the dam face. Jordan instructs Louie to start assembling the materials to repair the dam face. The estimated repair costs are $500.

While Jordan is surveying the current water situation, he is looking for areas of improvement. He takes measurements on some of the flumes and determines that Louie never got the slope correct on one of the replacement flumes. There is no grade beyond the first 100 feet of the flume. The bottom is two to three tenths high. The lack of a grade or slope is creating a slow spot in the water flow. Jordan estimates they need to set the flume end at a 15-degree angle to get the water velocity higher.

Before the end of the year, Jordan does purchase some water from the debris dam. However, the weather is not as warm and water demand has slackened. The North Fork Ditch was able to supply water to all their consumers for the summer of 1947. But Jordan knows that if demand continues to increase, he must make some modifications to the canal to handle the higher flows required to supply the demand next year.

Conclusion

Few people outside of the North Fork Ditch Company knew or understood how much work Loring K. Jordan put into the water system. He took over a fragile water canal, and in the face of increasing water demand, was able to keep the water flowing.

Probably no man knew the North Fork Ditch better than Loring K. Jordan in 1948. For 20 years he worked to improve the dam, water canal, reservoirs, and distribution. Jordan understood what the construction of Folsom Dam meant to this utterly historical water feature of California. In December of 1948, Jordan wrote a short history of the North Fork Ditch.

Jordan wrote one paragraph about the early mining days on the American River that could easily be applied to his time on the North Fork Ditch.

“All of the mining camps heretofore mentioned, the names of which are suggestive, and which at one time have been densely peopled, have an interesting history, if pains were taken to rescue it from a fast concealing oblivion, but the records are meager. Old timers are gone, and I fear that the most interesting pages connected with these early camps will never be written.”

Folsom Lake covered the North Fork Ditch and the early mining camps of 1849. Loring K. Jordan did leave some records for us to understand how the North Fork Ditch, 90 years after it was constructed, was still operating under the careful watch of his management.