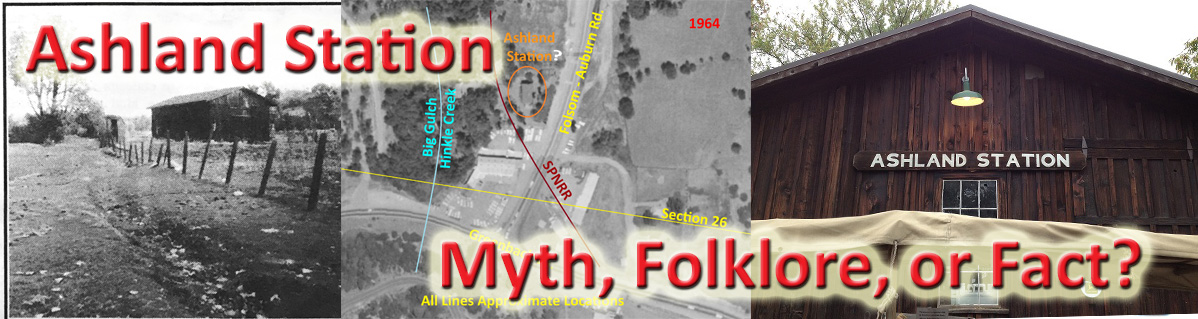

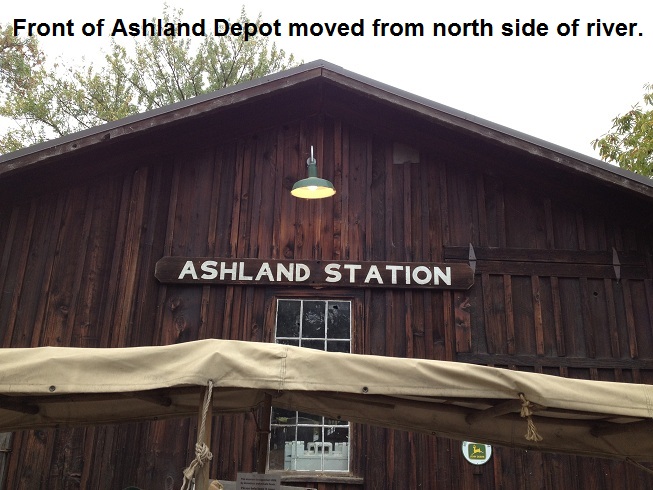

It is an old structure, weather worn, sitting on the corner of Wool and Leidersdorff streets in the Folsom historic district. Recently, the provenance of the structure known as the Ashland Station has been called a myth. While there is no definitive proof that this elevated structure of mortise and tenon construction was intimately involved with the Folsom to Auburn railroad, various documents and the construction method suggest that we should keep an open mind before dismissing local historical knowledge as to the structure’s original purpose.

Brief history of the Folsom to Auburn Railroad

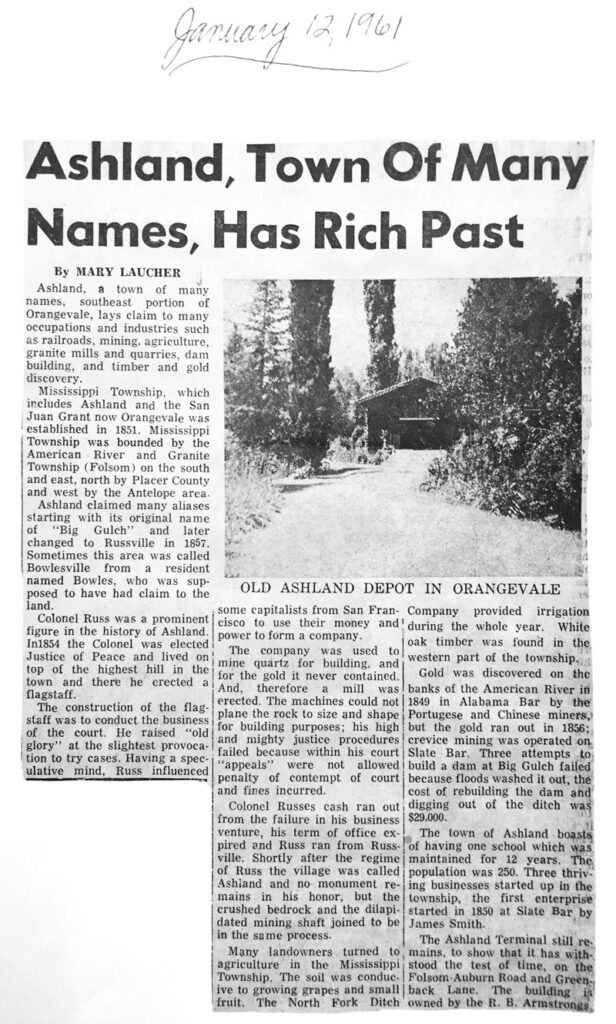

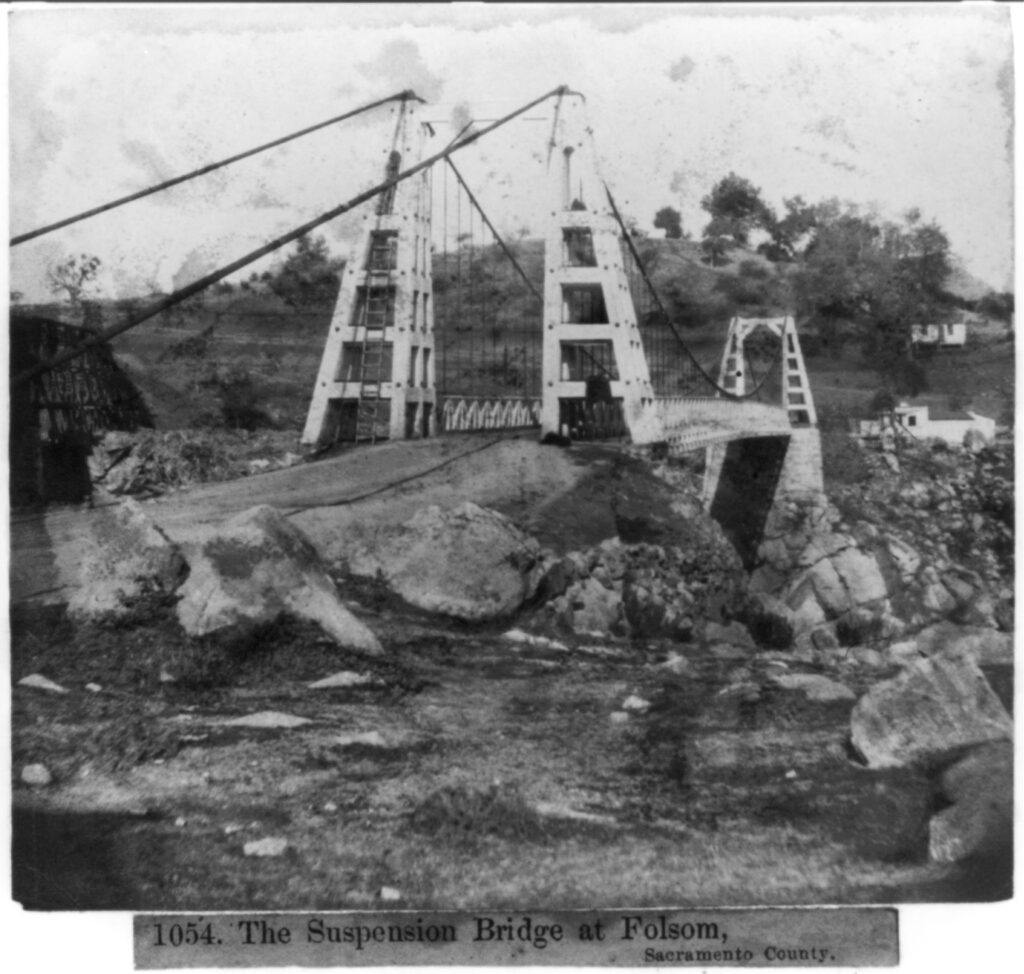

The Sacramento Valley Railroad came to Folsom in 1856. Shortly thereafter, the California Central Railroad was organized to extend the line from Folsom northwest through Roseville up to Lincoln. As the California Central was finishing the tall wooden bridge over the American River, community members in Auburn were wondering how they could get a rail line extended to their town. By 1859 the push was on to organize a railroad from Folsom to Auburn.

The bridge of the California Central connected the town of Folsom to the very small community on the northside of the American River known as Ashland. Once on the north side of the river, the California Central turned west, following the bluff above the river, and skirting the southern end of Ashland. The proposed railroad up to Auburn would technically start at Ashland and wind its way up to Auburn.

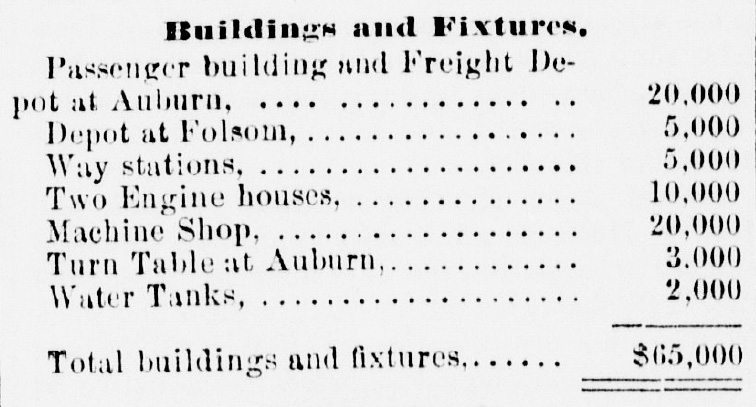

In an effort to expand the base of potential investors, the Folsom to Auburn railroad was incorporated as the Sacramento, Placer, and Nevada Railroad (SPNRR) with the hope that communities of Grass Valley and Nevada City would lend support. Civil engineer Sherman Day was hired to examine a rail line from Folsom up to Auburn along with a cost-benefit analysis.

In Day’s report he estimated the cost of a depot at Folsom at $5,000 and another $5,000 for way stations along the road.[i]

Even though Day’s report indicated a profit from the railroad venture, no cash investment was forthcoming. The only way for Auburn to invest in the railroad was to incorporate and issue bonds. Auburn incorporated in April of 1860 and later that year the people voted to issue $50,000 in bonds for the construction of the Sacramento, Placer, and Nevada Railroad.

The Problem with Maps

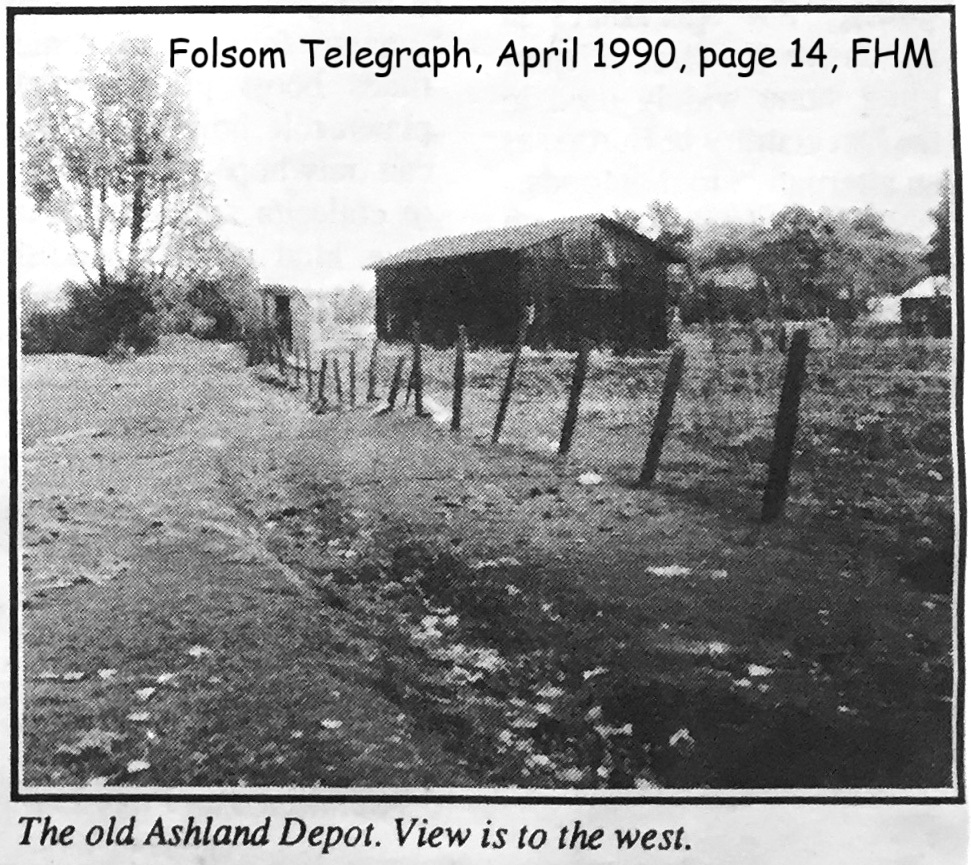

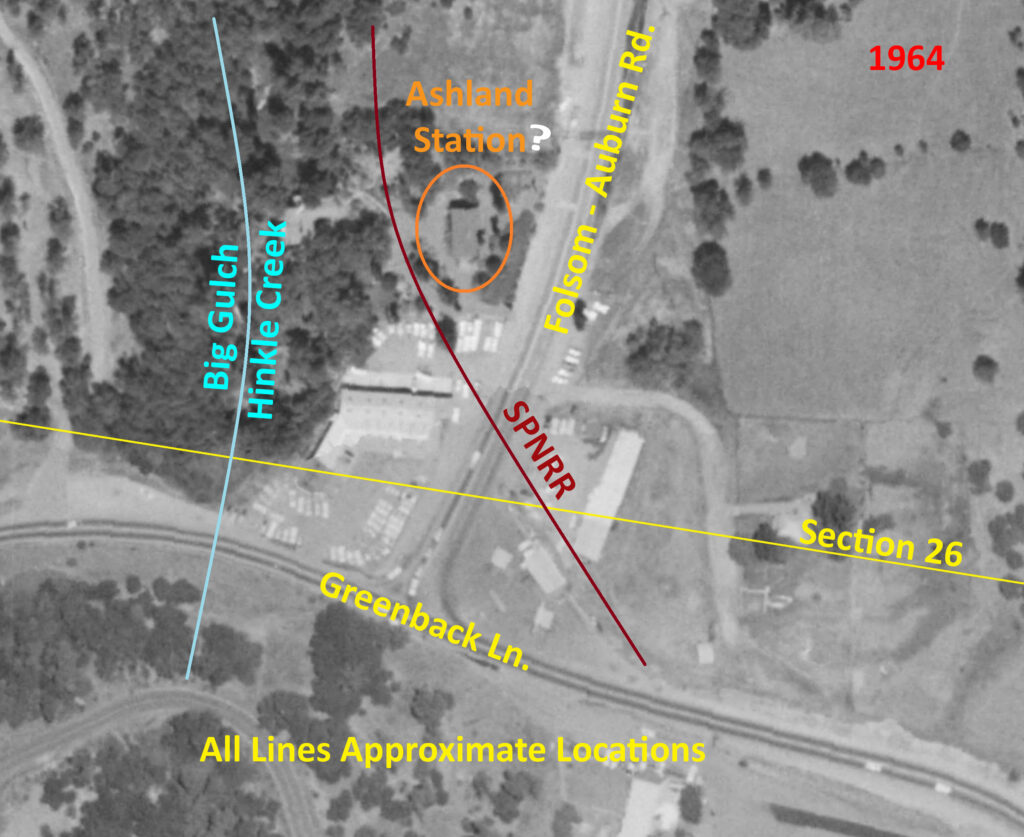

There are several valid arguments and criticisms over attributing the 19th century building known as Ashland Station as ever being associated with the Sacramento, Placer and Nevada Railroad that ceased to exist in 1864. One of the arguments against the Ashland Station, that was moved from the corner of Greenback land and Folsom-Auburn Road in 1973, was that it does not show up on any map of the era.

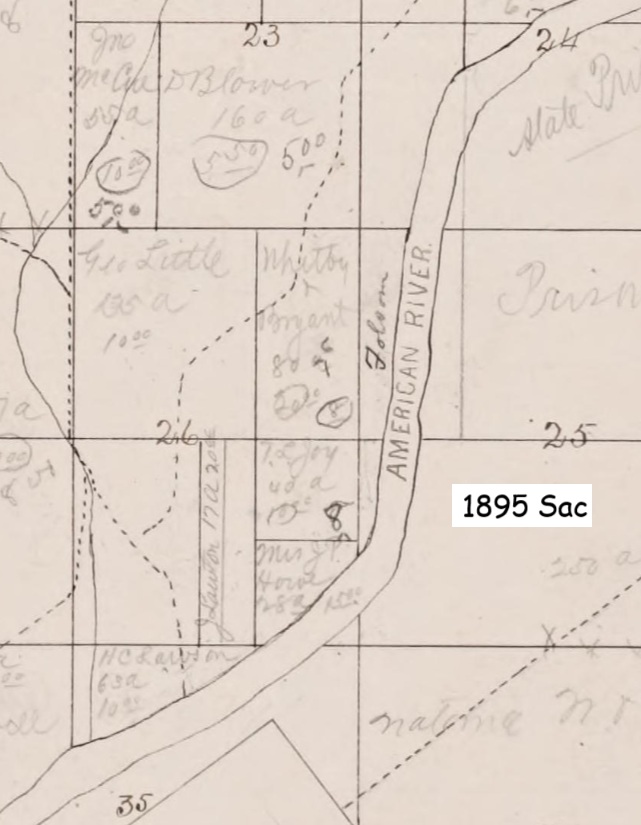

A minor structure may or may not have been included on any official map. The larger issue is that no official map was made until 1865 when the General Land Office (GLO) issued their official survey plat. Technically, all of the land was owned by the federal government and no settler could officially purchase any of the land until the GLO maps were issued.

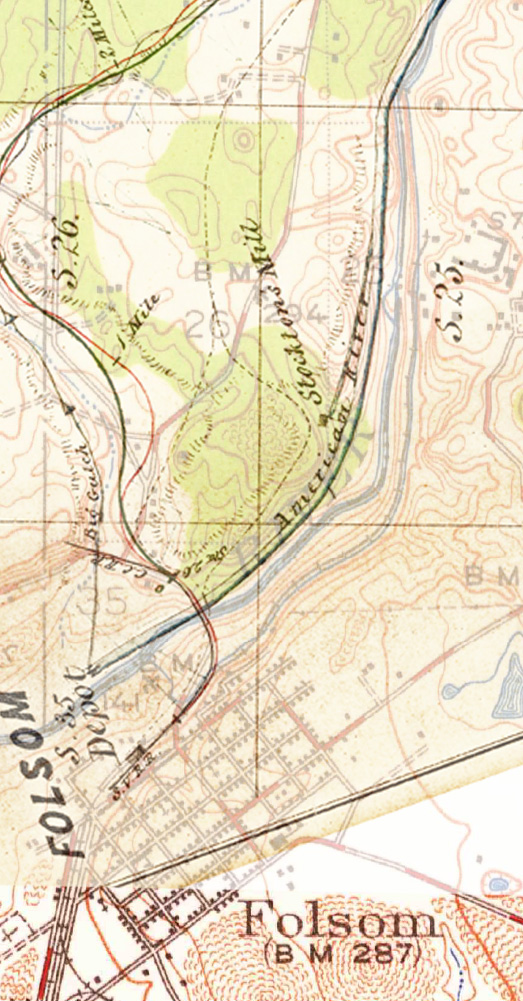

By 1865, the short two-year run of the Sacramento, Placer and Nevada Railroad had concluded. The GLO map of 1865 notes a railroad bridge over the American River, a line for the Lincoln Railroad (California Central Railroad), and one other road.

It would not be until the 1890s that the Sacramento County Assessor’s Office would depict the old right of way for the Sacramento, Placer and Nevada Railroad and it would be referred to as the Folsom to Auburn Road within grant deed descriptions

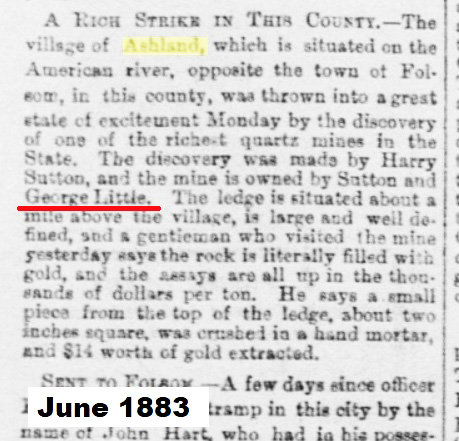

Even though settlers could not officially purchase or claim title to federal lands until the General Land Office maps were approved and released, families like George Little still recorded their claims with the county. The land descriptions were a mixture of metes and bounds descriptions and the impending Public Land Survey System township and range designations. These recordings with the County Clerk would help verify their claim of preemption so they could purchase the land directly from the federal or state government.

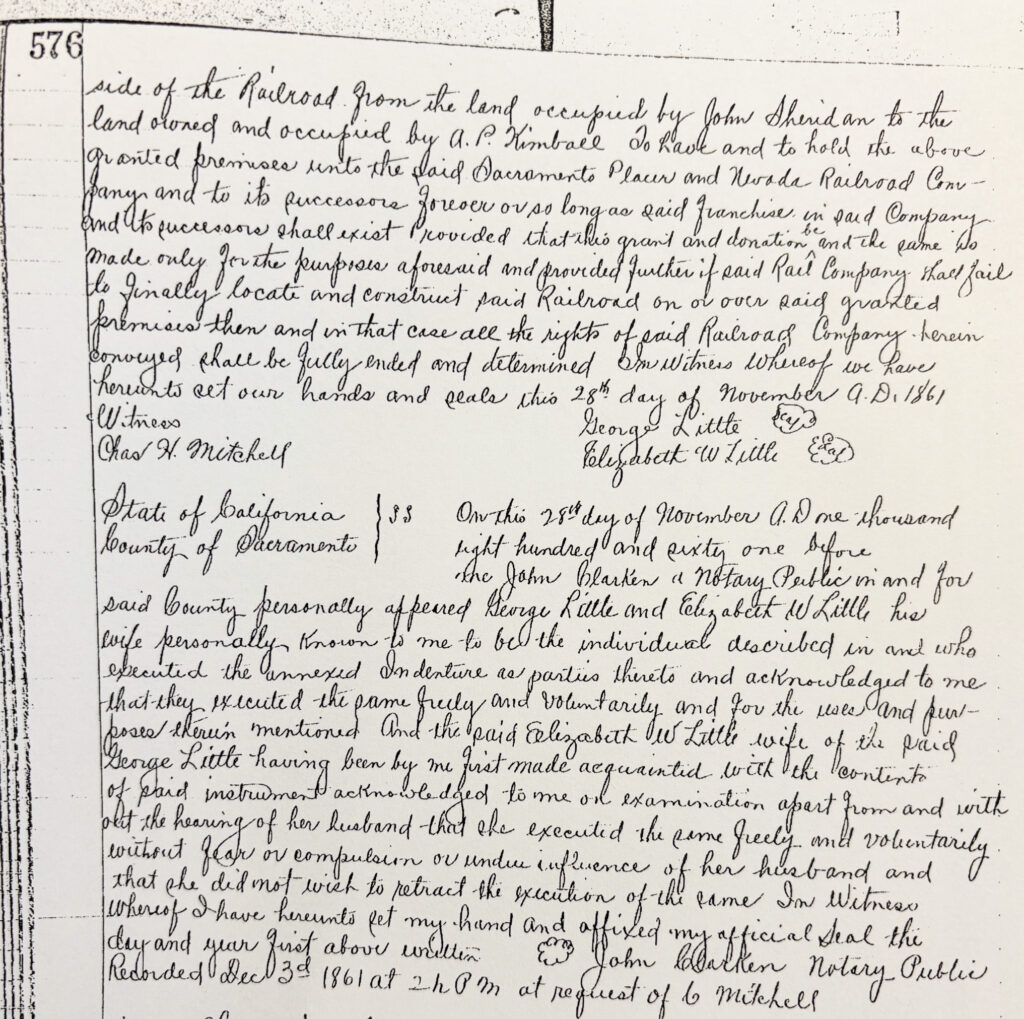

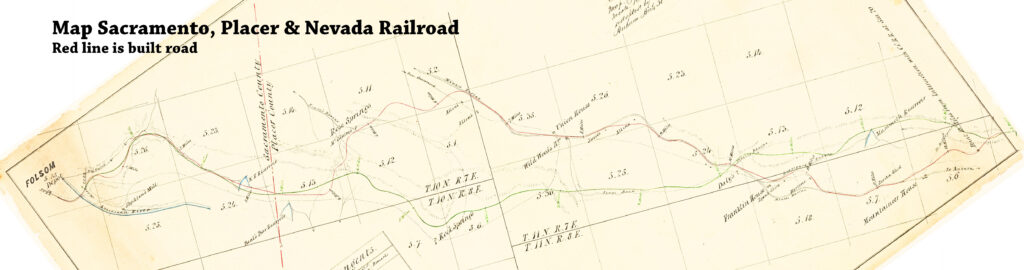

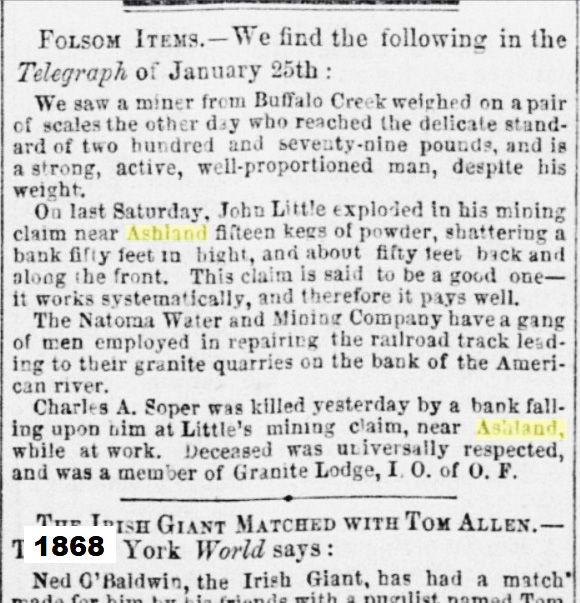

A map of the Sacramento, Placer and Nevada Railroad, as completed up to Rock Springs Road in Placer County, was dated August 30, 1861. In November of 1861, George and Elizabeth Little granted a right of way to the Sacramento, Placer and Nevada Railroad for nearly 100 feet in width for the length of the railroad as it crossed the land they claimed in Ashland.

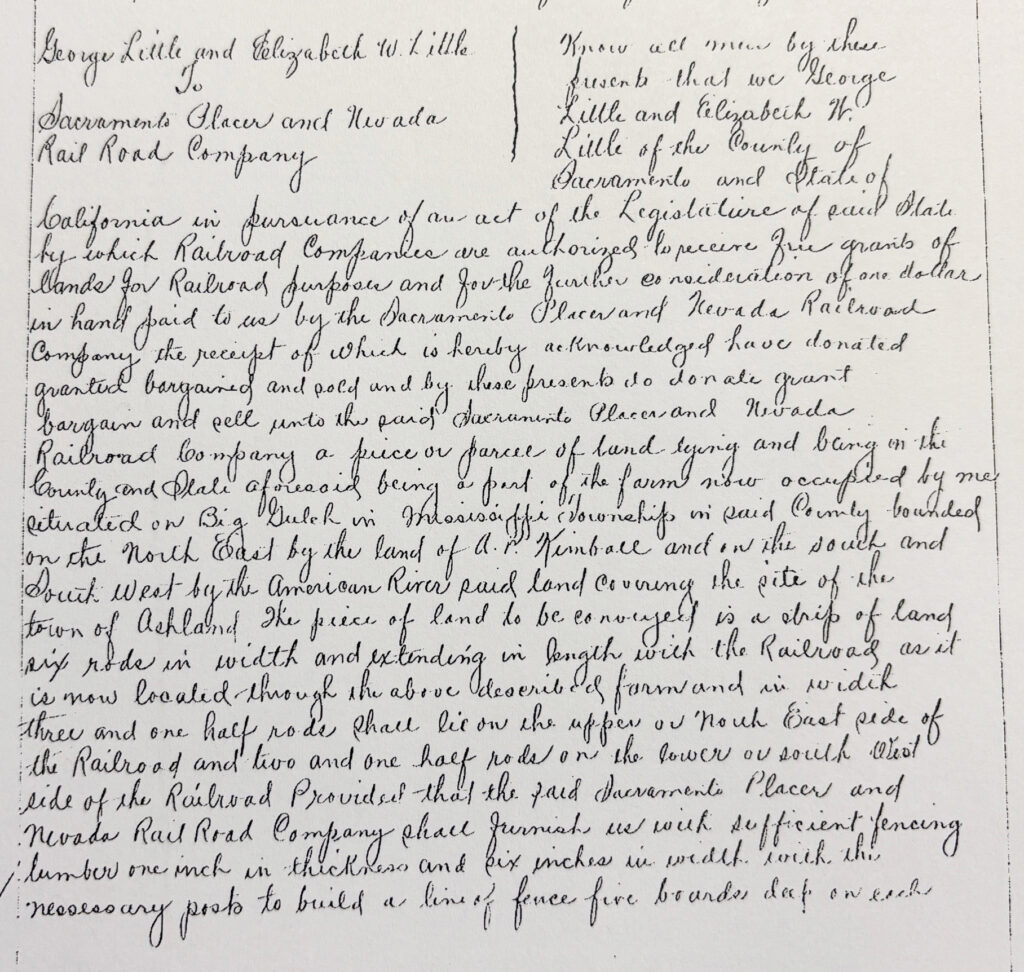

George Little and Elizabeth W. Little to Sacramento Placer and Nevada Rail Road Company

“…State of California in pursuance of an act of the Legislature of said State by which Railroad Companies are authorized to receive free grants of lands for Railroad purposes and for the further consideration of one dollar in hand paid to us by the Sacramento Placer and Nevada Railroad Company the receipt of which is hereby acknowledged have donated granted bargained and sold and by these presents do donate grant bargain and sell unto the said Sacramento Placer and Nevada Railroad Company a piece or parcel of land lying and being in the County and State aforesaid being a part of the farm now occupied by me situated on Big Gulch in Mississippi Township is said County bounded on the North East by the land of A. P. Kimball and on the south and South West by the American River said land covering the site of the town of Ashland. The piece of land to be conveyed is a strip of land six rods in width [approximately 33 yards] and extending in length with the Railroad as it is now located through the above described farm and in width three and one half rods [19.25 yards] shall lie on the upper or North East side of the Railroad and two and one half rods on the lower or south West side of the Railroad. Provided that the said Sacramento Placer and Nevada Rail Road Company shall furnish us with sufficient fencing lumber one inch in thickness and six inches in width with the necessary posts to build a line of fence five board deep on each side of the Railroad from the land occupied by John Sheridan to the land owned and occupied by A. P. Kimball. To have and to hold the above granted premises unto the said Sacramento Placer and Nevada Railroad Company and to its successors forever or so long as said franchise in said Company and to its successors shall exist. Provided that this grant and donation be and the same is made only for the purposes aforesaid and provide further if said Rail Company shall fail to finally locate and construct said Railroad on or over said granted premises then and in that case all the rights of said Railroad Company herein conveyed shall be fully ended and determined. In witness wherof we herunto set our hand and seals this 28th day of November A. D. 1861. George Little and Elizabeth W. Little. Witness Chas H. Mitchell.”[ii]

Note that the grant of land was narrower at the entrance and exit of the property. The nearly 33-yard width, far in excess of what a railroad needed, was reserved for somewhere in the middle. This extra wide grant of land suggests the railroad had other designs for the property such as another set of rails, storage yard, water tank, or a station. Also of note is that the property would revert back to George and Elizabeth if the railroad failed, which it did by 1864.

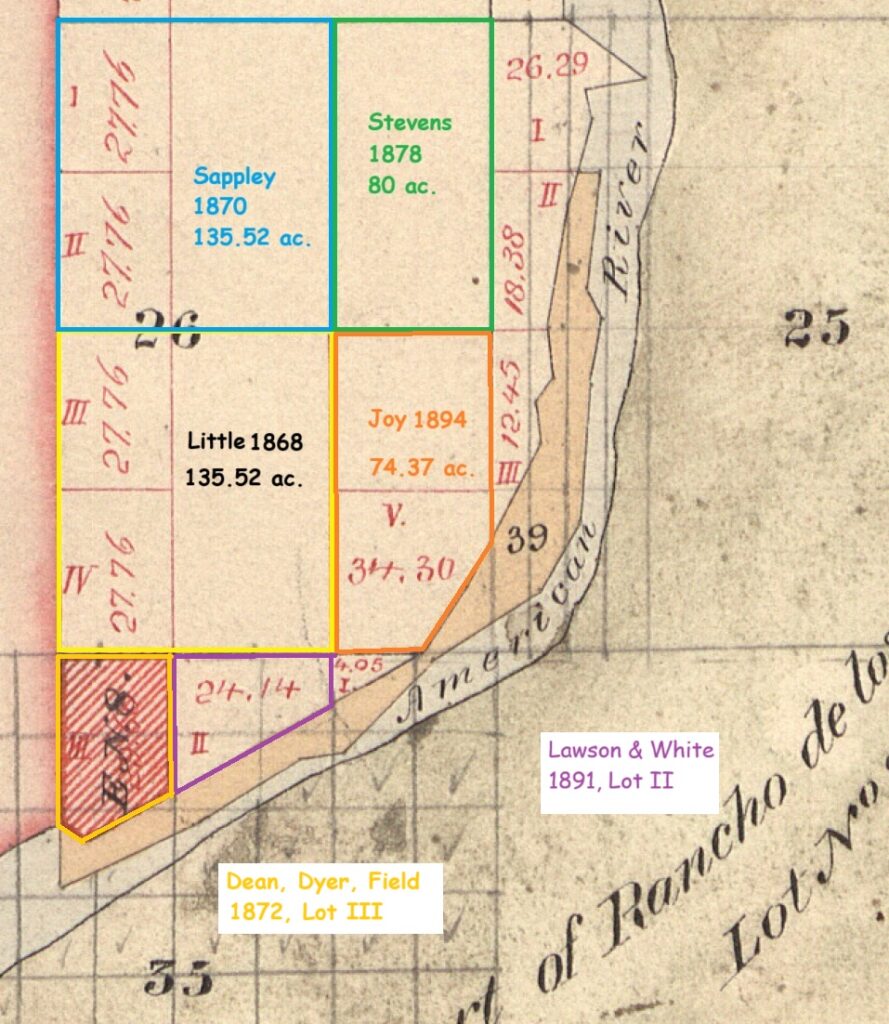

George Little would obtain a land patent to the property in 1868, several years after the tracks of the railroad had been removed. Unlike the description in the 1861 deed with railroad, the property did not extend down to the American River as indicated in the grant deed to the railroad. Because the San Juan land grant was directly to the west of Big Gulch, known today as Hinkle Creek, Little’s property was broken up into three sections. There were two small sections known as lots 3 and 4 that extended over Big Gulch over to the San Juan land grant.

A map of the Sacramento, Placer and Nevada Railroad created in 1861 shows a proposed route (green line) and the as-built road (red line) up to its terminus by the company when it was operating. The map is dated August 30, 1861. The grant deed between Little and SPNRR is dated November 28, 1861. The Ashland Station structure, if constructed by the railroad, may not have even been built when the map by Chief Engineer J. P. Robinson was confirmed as the final route of the Lower Division of the railroad. If the Ashland Station had not been built at the time the map was prepared, it most likely would not have been included on the official map.

The 1861 map of the railroad does not indicate any station structure within section 26. It also does not indicate any other stations or depots north of the American River.

When we combine the 1861 SPNRR map with 1941 USGS topographical map, the general route of the railroad comes into focus as it traversed through Little’s property.

A low-resolution aerial image from 1964 shows what appears to be Ashland Station structure in the approximate location observed before it was moved in 1973. The structure is sandwiched between Folsom-Auburn Road on the east and Big Gulch/Hinkle Creek to the west. This was part of the property, lot 4, that George Little granted to the Sacramento, Placer and Nevada Railroad in 1861.

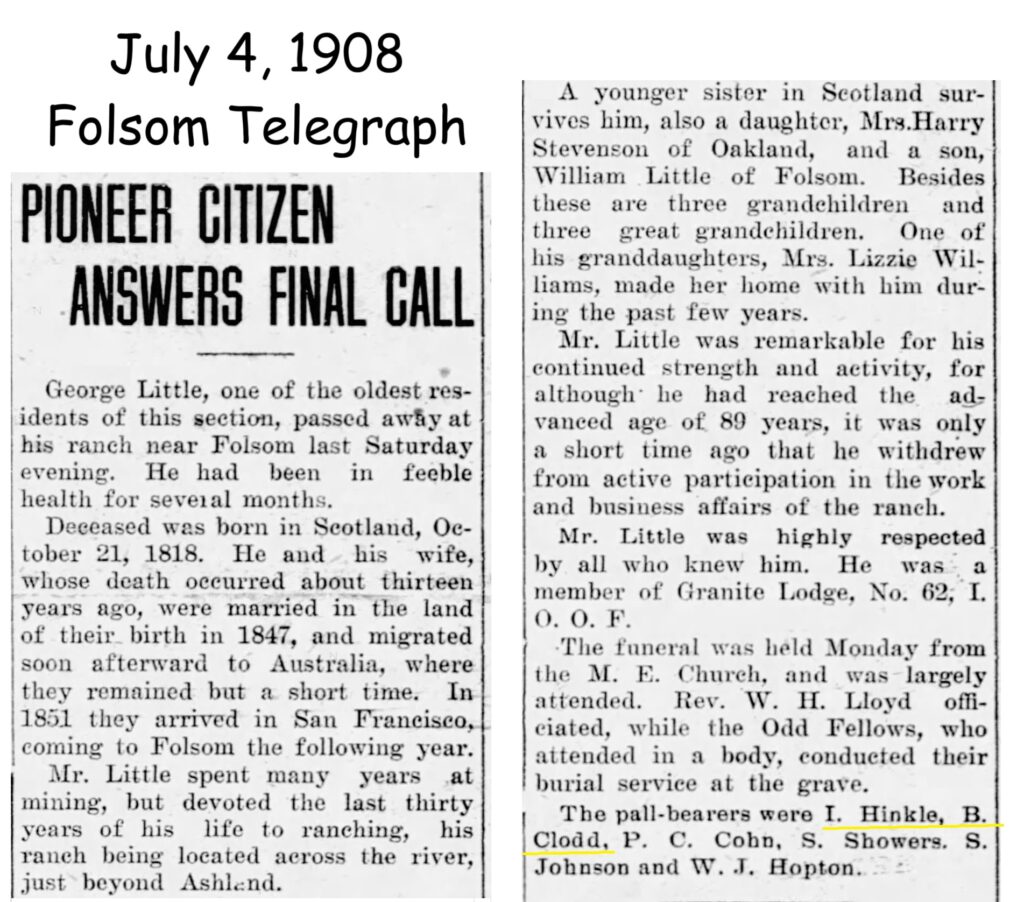

George and Elizabeth Little

Of all the immigrants who came to the Big Gulch area, few stayed longer than George and Elizabeth Little. George arrived in 1851 and remained until his death in 1908. George and Elizabeth had a son, William Little, who also remained in the Ashland area and died in 1930.

In addition to gold mining and farming, George Little sold various parcels of his property to other people such as John F. Cardwell, John Lawton, and W. W. Latham. The latter two men ran the local hardware store and was the place for election polling and tax collections. George also transferred property to his son, William, north of his original land patent.

It is not unreasonable to assume George Little passed his experience and memories of the Sacramento, Placer and Nevada Railroad to his children, neighbors, and other members of the Ashland community. If all the original residents had left the area after the railroad disappeared, the institutional memory of the elevated structure known as the Ashland Station may also have evaporated.

In 1885, Isaac Hinkle bought a piece of property from John T. Cardwell who had originally bought the lot from Little. Hinkle would become the superintendent of the North Fork Ditch that delivered water into Ashland for mining and farming. After buying some property north of Asland in 1902, Hinkle would plot out the Inwood Colony, like Cardwell’s Colony. The subdivision map submitted to Sacramento County notes that the road running between the lots was the old railroad right of way.

It was only through local knowledge that the Folsom to Auburn road had been graded by the old railroad. No detailed map of the Sacramento, Placer and Nevada Railroad exists at Sacramento County that I have seen. Isaac Hinkle had to have learned of the origins of the road from fellow Ashland residents such as George Little.

Institutional Memory Folklore

Locally, people knew of the old railroad, but its existence was not formally recognized by the county government. George Little had participated in the creation of the railroad with his grant to the company. The grant to the railroad is a fact. The actual road, fences, buildings – some long destroyed – became part of folklore. The Ashland Station is part of the railroad folklore.

Unlike today, rural properties – most of Sacramento County in the 19th century – did not assigned numeric addresses. A house or residence was referenced in descriptive terms such as being 50 feet west of the road, north of the bridge. The local parlance was to refer to a structure, property, or house for the person who originally built or owned the land. It is not uncommon to read references of “the family moved into the old Clodd house” or “they now live at the old Hector ranch.”

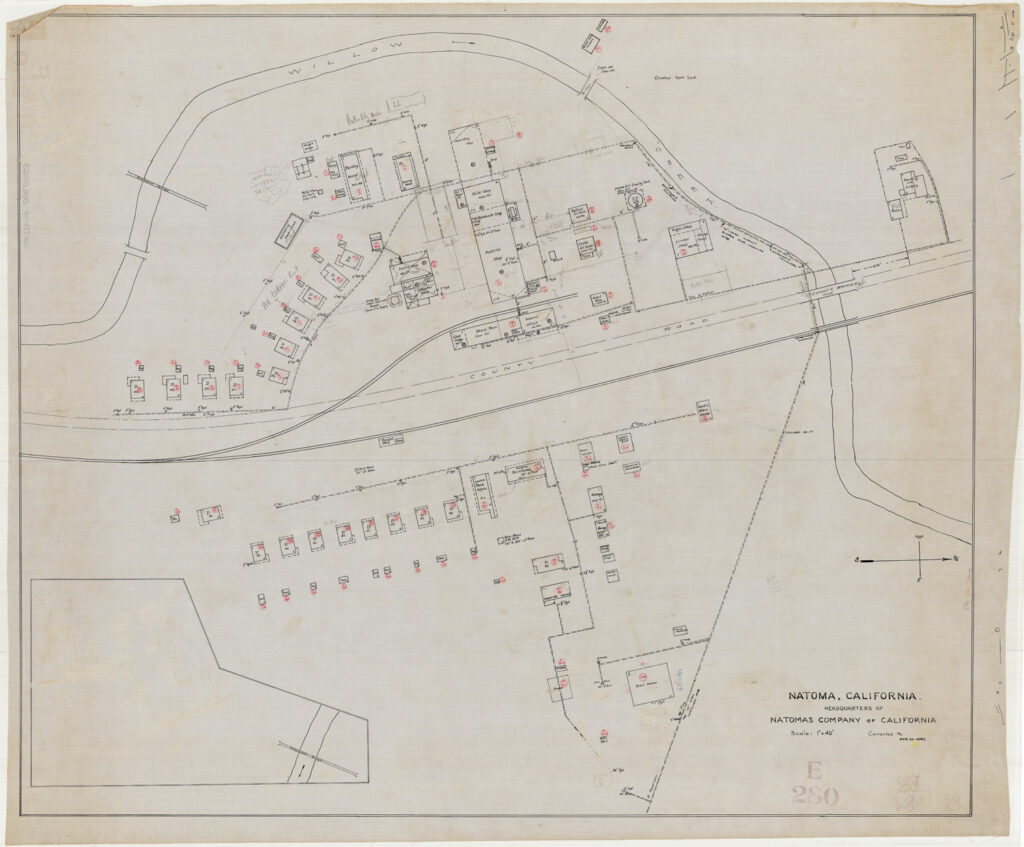

While the author or local residents knew where the Clodd house or Hector ranch was located, those specific places can be hard to find 100 years later. Through institutional memory and folklore, places can be remembered and honored. Most people today do not know the reference for the street Natoma Station at Blue Ravine and Folsom Auburn roads. At that location was the corporation yard for the Natomas Company engaged in gold dredging.

Vance lane, east of Folsom Auburn Road in old Ashland, was named for Charles Vance who purchased the property from Benjamin Clodd in 1936. Natoma Station and Charles Vance were memorialized as historic enterprises and early 20th century residents. As a street was recognized for Charles Vance, residents of old Ashland kept the memory and folklore of the Ashland Station circulating.

Conflating History

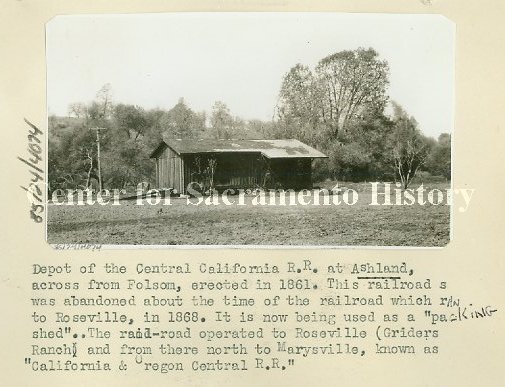

People and newspaper reporters passing through the region picked up the folklore and sometimes conflated history when reporting the old structure. A 1938 photo from the Eugene Hepting collection at the Center for Sacramento History captions the Asland Station structure as being the depot for the California Central Railroad. Another set of images attributes the structure to the Sacramento Auburn Placer R.R.

The probability of the structure being associated with the California Central are fairly low because of its siting at least 100 yards from California Central line along Greenback Lane. The second attribution is closer, even if the author did misname the SPNRR as the Sacramento Auburn Placer R.R.

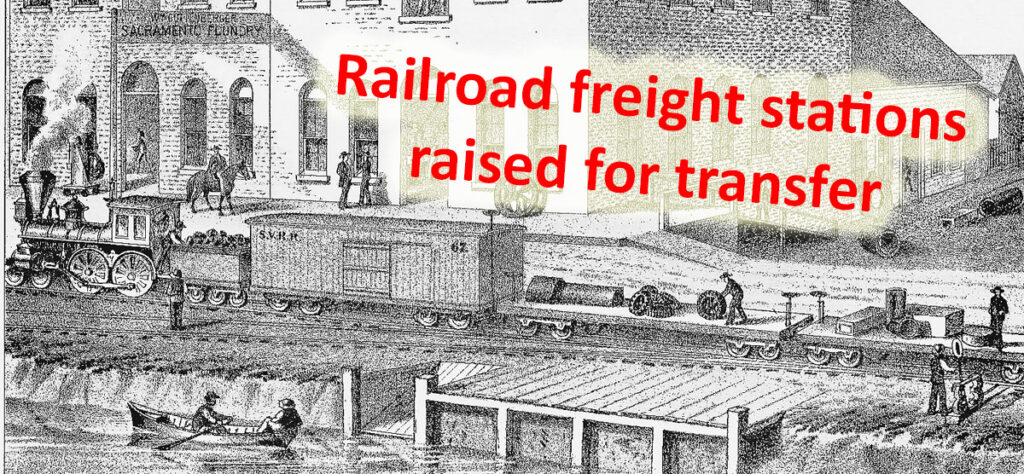

Another newspaper story from 1961 found at the Folsom History Museum, erroneously states the Ashland Station structure sits in Orangevale and christened it as a depot as opposed to a station. The difference between a depot and station are relatively small. In general, depots of the time were focused on passenger ticket sales whereas stations were focused as stops for freight traffic.

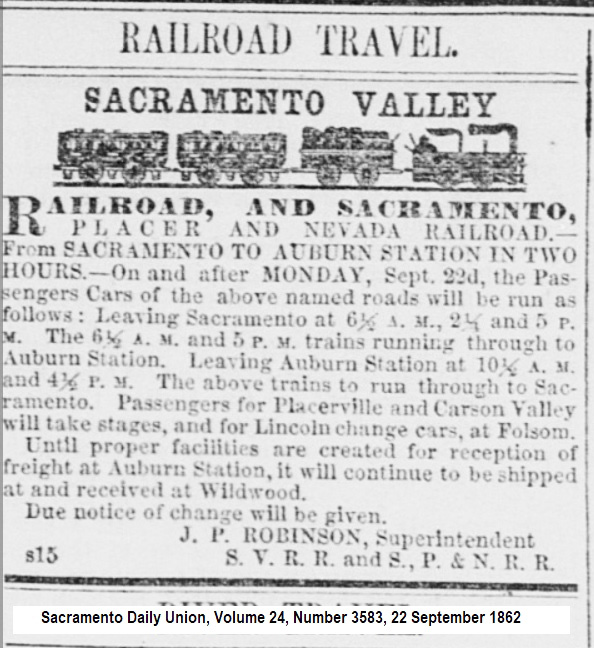

Advertised Scheduled Timetable Argument

Another criticism of the Ashland Station is that its location was never noted on any railroad timetable for arrival or departure. Railroads of the 1860s in California had not developed the precise schedule timing that trains would adhere to later in the 19th century. There could be frequent stops to load or unload freight along the route, not to mention cows on the tracks or equipment failures.

The advertisements were a means to let potential passengers know of their estimated arrival at the end of the line. Consequently, way stations may not have been noted on any timetable or advertisement. The Sacramento Valley Railroad had stations between Sacramento and Folsom, but they were not always listed on timetables. Other potential stations along the SPNRR such as Wild Wood’s house or the Franklin house were not listed on any SPNRR timetable advertisement that I’m aware of.

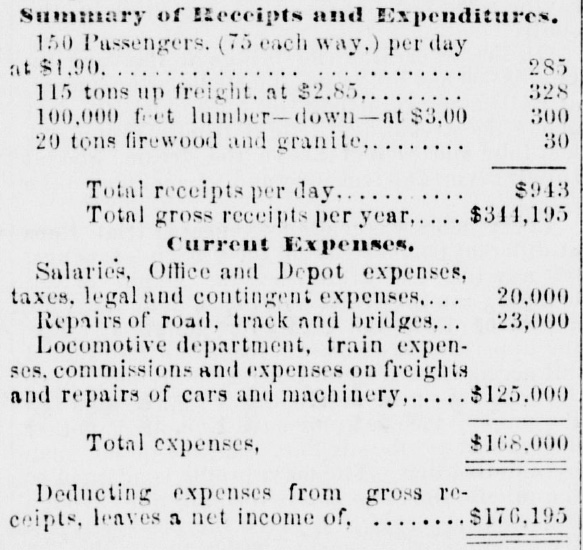

The stations between the point of departure and the terminus were usually for local freight. Sherman Day’s report on a Folsom to Auburn railroad stated, “A railroad from Folsom to Nevada [county] is more needed for freights than for passengers:…” Of the estimated daily revenue of the proposed railroad, Day estimated passenger receipts would equal $285, while freight would generate $658 on a daily basis.

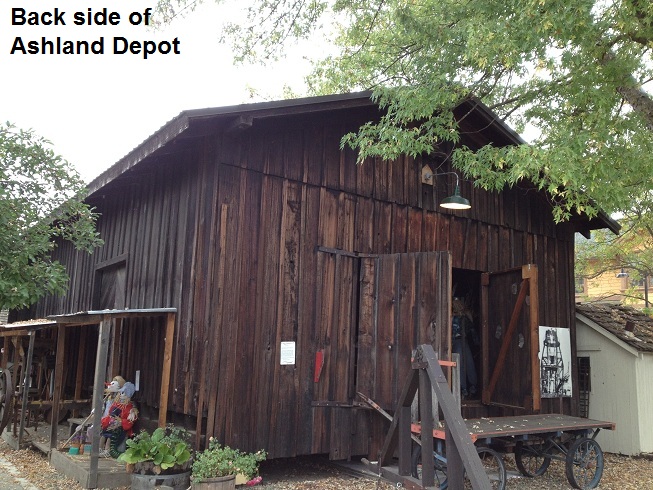

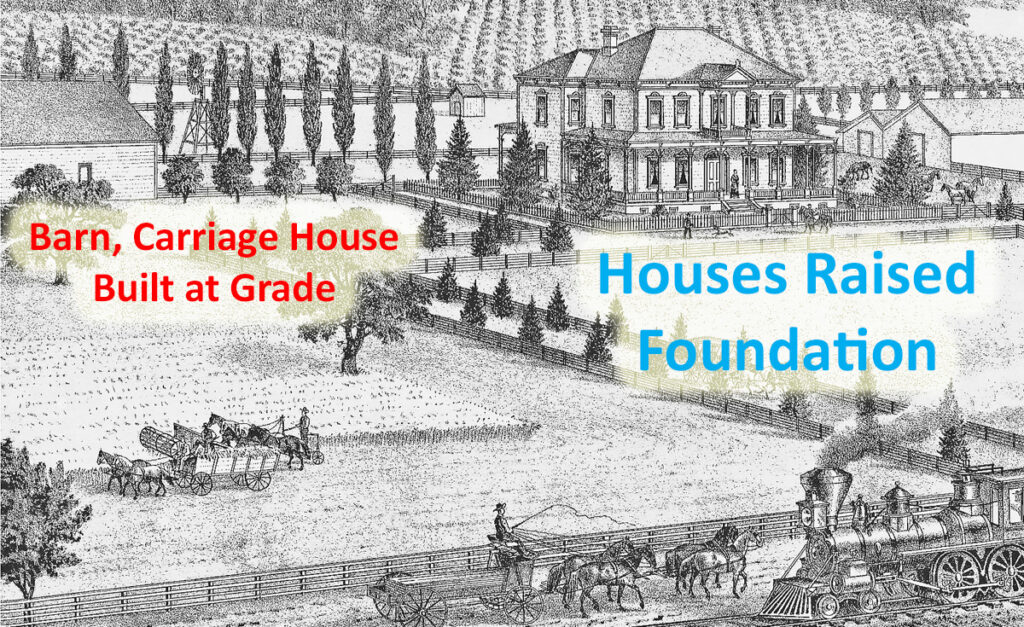

If the approach of the SPNRR was to maximize freight receipts, way stations geared for fruit, lumber, stone, or bulk item transfer to rail cars would be strategically located along the railroad. Was the Ashland Station, with its elevated stature, designed for freight transfer to the SPNRR? While that question cannot be answered, the station was certainly not designed to be a barn.

The barns and outbuildings of the region were built at grade. When the structure was above grade, moving animals or farm equipment into the barn was neither practical nor efficient, even if you had a ramp. The Ashland Station is more reminiscent of the packing and loading sheds along the railroad in Loomis and Newcastle. Current images of Ashland Station at Folsom do indicate a ramp on one side of the building. This would be logical for moving heavier objects into the building and them over to the front for possible transfer to a flatbed railcar.

Mortise and Tenon Construction

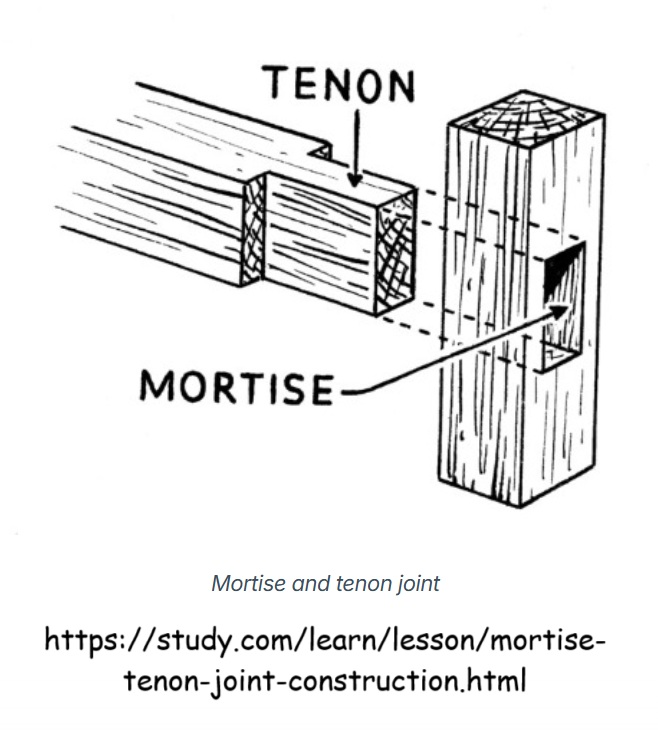

Regardless of whether the Ashland Station was part of the railroad, its construction is historic and worthy of preservation. The structure was designed and constructed with mortise and tenon joints. One end of a beam has its profile reduced through sawing and chiseling (tenon) and is inserted into an adjoining beam that has a hole or slot (mortise) to accept the narrowed piece. When metal fasteners such as nails or brackets were scarce or nonexistent, mortise and tenon joints provided economic, yet very strong, construction.

Mortise and tenon construction required more experience, planning, design, and time than a construction method where milled lumber is just sawn and nailed together. Men who had the necessary experience with mortise and tenon construction were not uncommon in 19th century California. If the Ashland Station structure was meant to be a simple barn, built at grade, it is unlikely the owner would have gone to the expense of the more time-consuming mortise and tenon construction.

Royall and May Armstrong

The last residential owners of the property where the Ashland Station was located north of Greenback Lane were Royall and May Armstrong. They purchased the property in 1939. Royall was a math teacher at San Juan High School. Royall and May had one child, Phillip, born in 1929. It is unknown to what extent Royall and May continued farming or ranching on the property.

Armstrong, the school teacher, did get a mention in the journal of Loring Jordan, who was the General Manager for the North Fork Ditch.

“Went by Ashland and found Woods where he was working on a piece of pipe at the junction of the extreme low end of the Ashland line. About 20 ft. of pipe has gone completely out and he is attempting to replace it with a piece of 6” pipe we had in the yard. First there was not enough water and about a week ago during the dry spell both Howard and the school teacher (Armstrong) were irrigating. When Woods shut off both Howard and the Vance house on the top of the hill it became short.” – March 21, 1946.

In 1953 Royall and May deeded a strip of their property to Sacramento County for the widening of Folsom – Auburn Road, possibly related to the increased traffic associated with the construction of Folsom Dam. Even though the widening of the road included close to half an acre of Armstrong’s property, it obviously did not encroach on the Ashland Station and no mention of the structure is mentioned in the deed grant.

Royall would live out his life in Ashland dying in 1968. May would die in 1972. The land originally conveyed to George Little in 1868, finally passing into the possession of the Armstrongs, was ideal real estate for a strip mall. Local residents of old Ashland and Folsom organized to move the Ashland Station, that they had driven by so many times in the past, over to Folsom for permanent display and conservation.

Substantial Structure

Ashland Station is a well-built and substantial structure. There are few barns of the era that could have withstood being jacked up, placed on a flatbed trailer, and moved, all while remaining sound. In short, any craftsman would have been proud to have their name attached to the structure.

It was common practice to attribute important and noteworthy structures built in the 19th century to the builder or owner. There was the Birdsall dam built on the North Fork of the American River in the 1880s. Kelly’s water wheel in the North Fork Ditch at Rattlesnake Bar. Avery’s Pond associated with the landowner that was a mud settling pond for the North Fork Ditch.

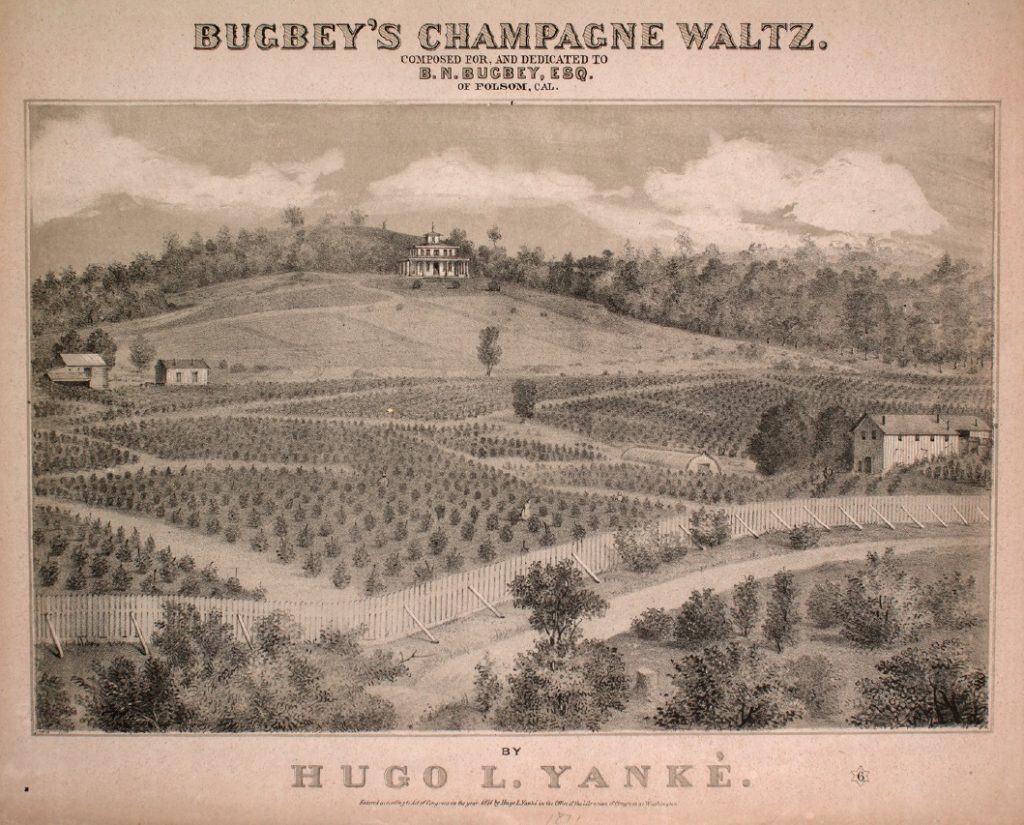

The original Hinkle reservoir – filled in with the construction of Folsom Dam – so referred to because Isaac Hinkle bought the property for the North Fork Ditch in 1902 and was the company’s superintendent. The Kinsey and Thompson wire suspension bridge between Folsom and Ashland. Long after Benjamin Norton Bugbey had left his Natoma Vineyard, the location was referred to as Bugbey’s old vineyard.

If the Ashland Station was built by George Little, or one of the successive property owners such as Benjamin Clodd, Charles Vance, or Royall Armstrong, I have no doubt that local residents would have attributed the easily seen substantial structure to the owner or builder. It seems as if the elevated structure with unusually solid construction, better than most houses, clearly seen from the Folsom to Auburn road, had always been referred to as the Ashland Station, not by the name of the builder.

Finally, during the time of the Sacramento, Placer and Nevada Railroads short existence, the United States was in a civil war. Some routine federal government work slowed down or stopped until after the war. Many General Land Office maps seem to have been delayed until survey work could resume after the war. In addition, the relationships between men were strained depending on one’s political leanings. Lastly, some common goods and hardware were not available. It would be reasonable to resort to a mortise and tenon construction if certain construction items were expensive or hard to obtain.

Conclusion

It was the folklore, with no documented evidence, that this old weather-worn structure was determined to be historic. The structure, used for decades as an elevated barn and packing shed for local fruit harvests, was unambiguously believed to be part of the Sacramento, Placer and Nevada Railroad. The belief in the historic nature of the structure was the result of oral attribution of its provenance.

I am the first person to voice a healthy skepticism regarding folklore. While folklore is usually born from a nugget of truth, oral history often becomes conflated with other events and embellished over time. It was historical research that led me to learn that it was the U.S. Supreme Court who had the final opinion and decree on the map of the Leidesdorff land grant of the Rio De Los Americanos in 1864. The local lore was somewhat different.

While oral history, institutional memory, and folklore can be riddled with misinformation, it should not be dismissed. The Ashland Station is not depicted on any map or noted in any newspaper story of the 1860s, as far as I have found. Only George Little could definitively tell us if the Sacramento, Placer and Nevada Railroad company built the structure or not.

In his absence, we are left with a grant deed to the railroad across his property where the structure resided for decades. The elevated construction of the building using mortise and tenon joints is out of character for most barns built in the area. Because of the history of the railroad and the construction method, I feel there is a high probability of the structure being associated with the railroad.

Regardless, the building is historic. I applaud those citizens who rallied to raise money to lift the Ashland Station from its foundation and move it across the river to Folsom. To those people, the Ashland Station was not a myth. The building was part of their history and identity as a community. We should honor the spirit of those community members for their recognition that history is important and needs to be preserved. Such community spirit is what drives all local preservation projects.

I am also grateful to the City of Folsom for allowing Ashland Station to be located in the historic district and to the Folsom History Museum for the care and stewardship they have bestowed upon this 19th century structure. Please visit the Asland Station in Folsom’s historic district as it is a visual treat from the region’s history.

YouTube Video of Ashland Station history.

[i] Placer Herald, March 31, 1860.

[ii] Sacramento County deed document number 1861112030575