Documents from the American River Water and Mining Company provide a small glimpse into the life of Chinese men on the American River between 1858 and 1868. Wage receipts from 1863 show how numerous Chinese men were employed by the American River Water and Mining Company to repair and clean the North Fork Ditch. Additionally, weekly water collection reports document water sales to Chinese men for mining and irrigation along the American River.

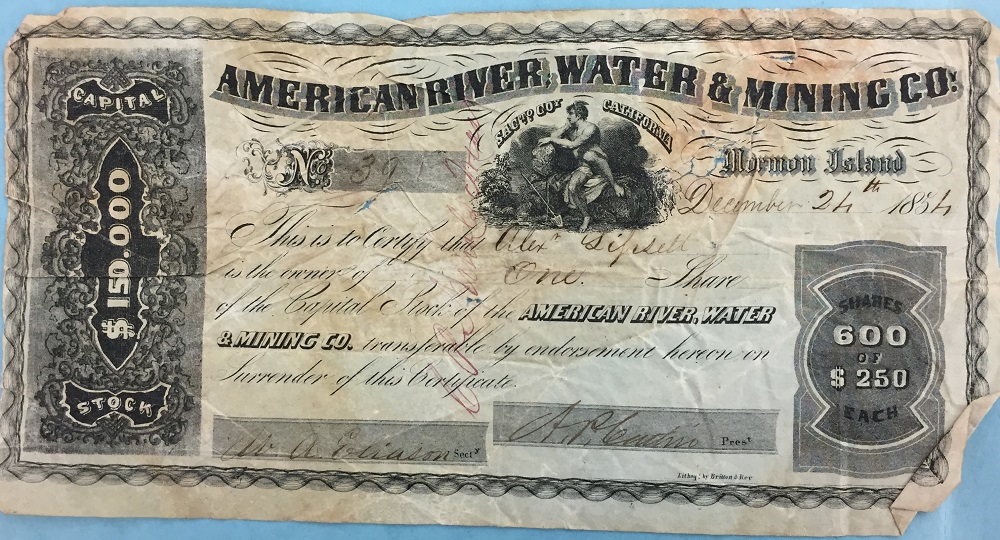

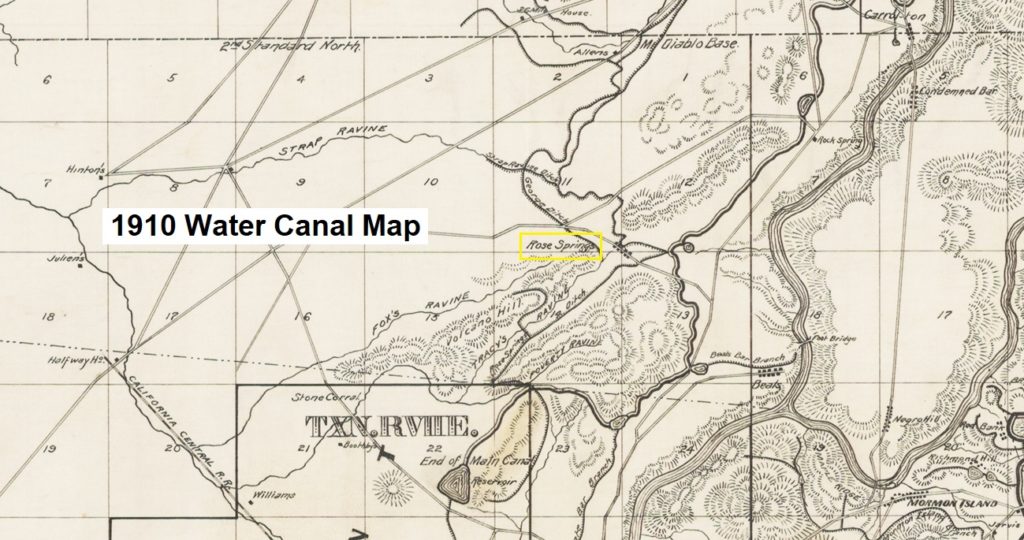

The American River Water Mining Company was formed in 1854 to construct the North Fork Ditch along the North Fork of the American. The main water ditch ran from a dam at Tamaroo Bar, just below Auburn, south down to the confluence of the north and south forks of the American River above Beal’s Bar. The water project would be extended through various branch canals to service Ashland, opposite Folsom, Mississippi Bar, and Sailor Bar. Another branch called the Rose Springs ditch would supply water west to Tracey’s Ravine, Foxes Ravine (Linda Creek), and Miner’s Ravine.

Amos Catlin was one of the organizers of the American River Water and Mining Company. In 1852, he was the driving force organizing the Natoma Water and Mining Company that had virtually completed the Natoma ditch on the South Fork of the American River by 1854. Catlin served as president of both the Natoma and American River water companies. The documents related to Chinese mining and labor activities on the American River are located at the Huntington Library, Catlin Papers, Box 2 and 5.

Chinese Labor on the North Fork Ditch of the American River

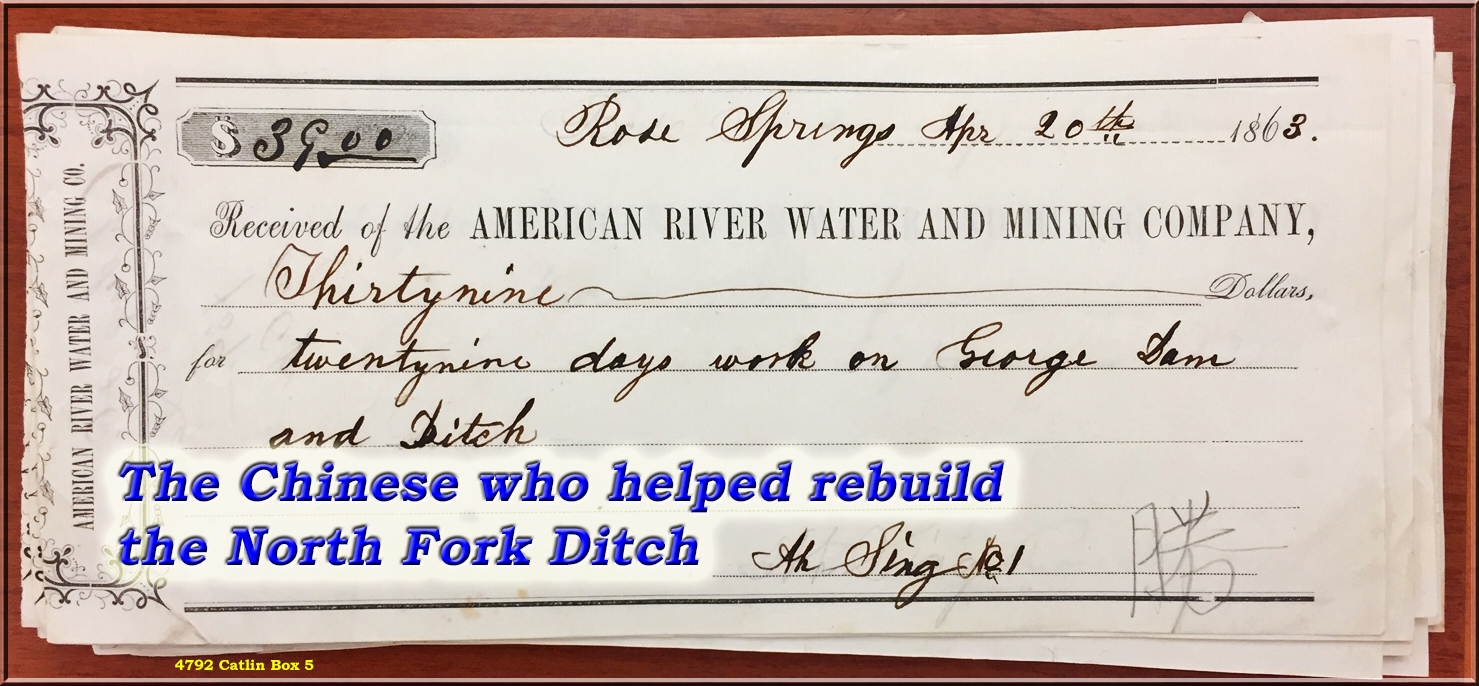

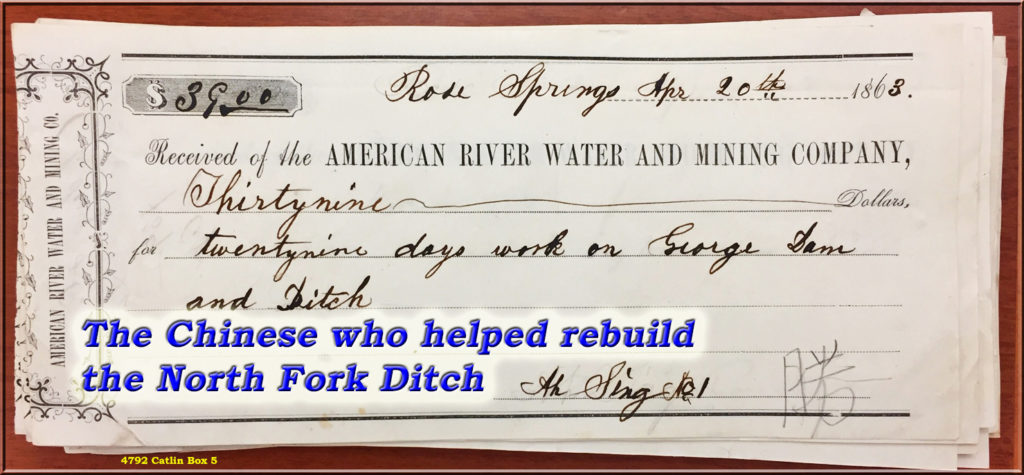

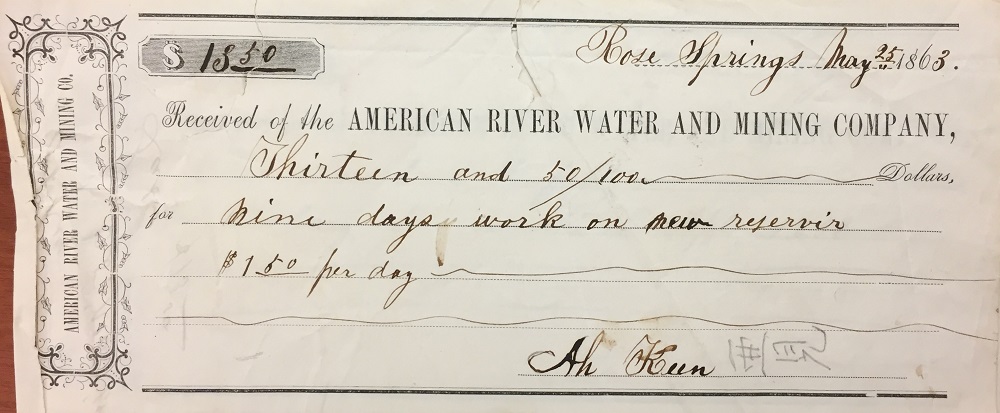

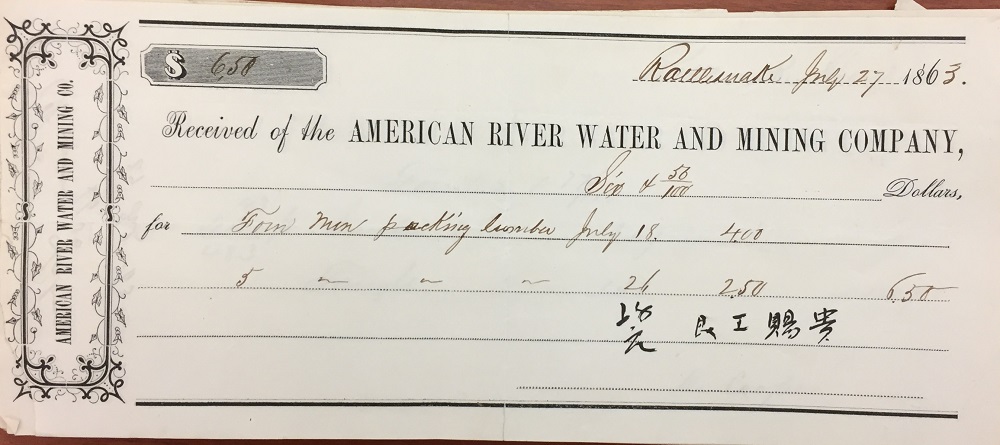

The wage receipts that encompass Chinese employment are all from 1863. There are 139 receipts that include payments for interest to note holders, salary, parts, service, sales commissions and labor payments. A majority of the receipts, 67, are for labor and document cash payments to men for their work on the North Fork Ditch.

It is hard to speculate if the labor payments are representative of the employment at the American River Water and Mining Company for its existence from 1854 through 1872. However, the years 1862 and 1863 represented a rebuilding phase for the North Fork Ditch. The catastrophic flooding of 1862 destroyed the dam, wooden flumes, and earthen ditches along the North Fork of the American River from Auburn down to Rattlesnake Bar, where the ditch was particularly close to the river.

Not only had the floods carried away much of the North Fork Ditch, it also washed away much of the mining structures and equipment. The bulk of revenue for the American River Water and Mining Company was from water sales to gold miners. Now, both the means to deliver the water and the consumers for the water had been washed away. The American River Water and Mining Company was forced to take out more loans and cut expenses by reducing salaries, eliminating positions, and finding ways to reduce the costs to repair and clean the canal structure.

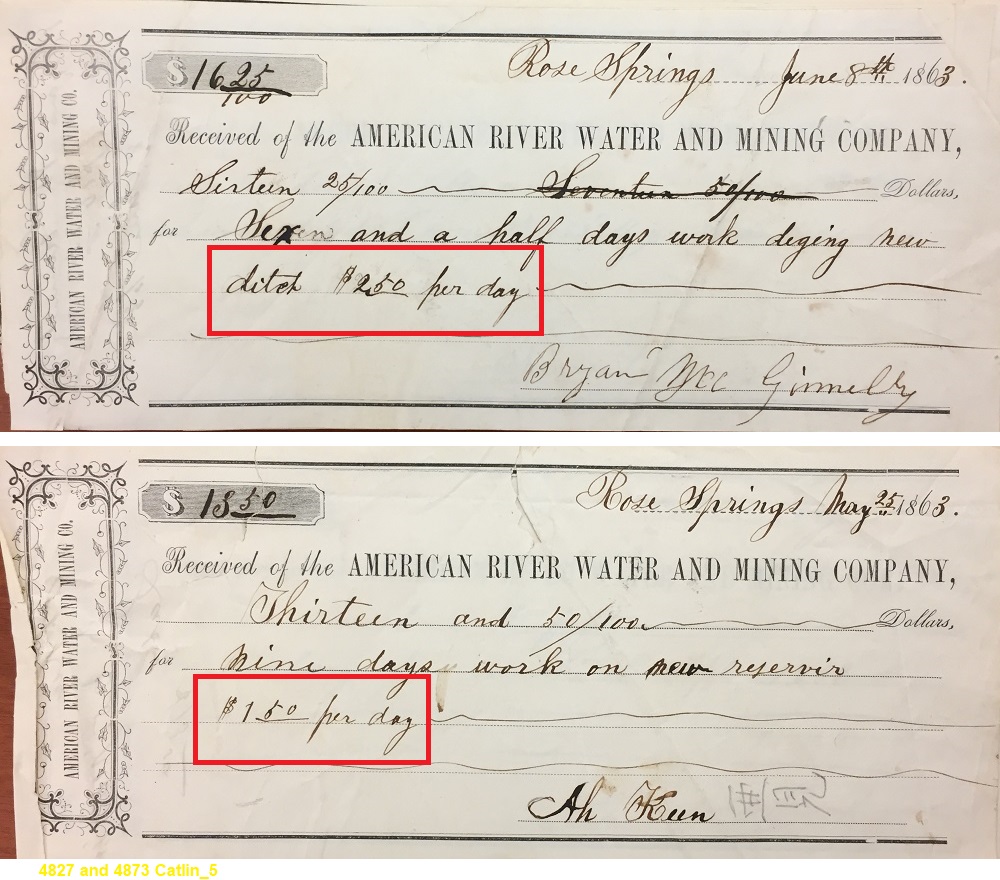

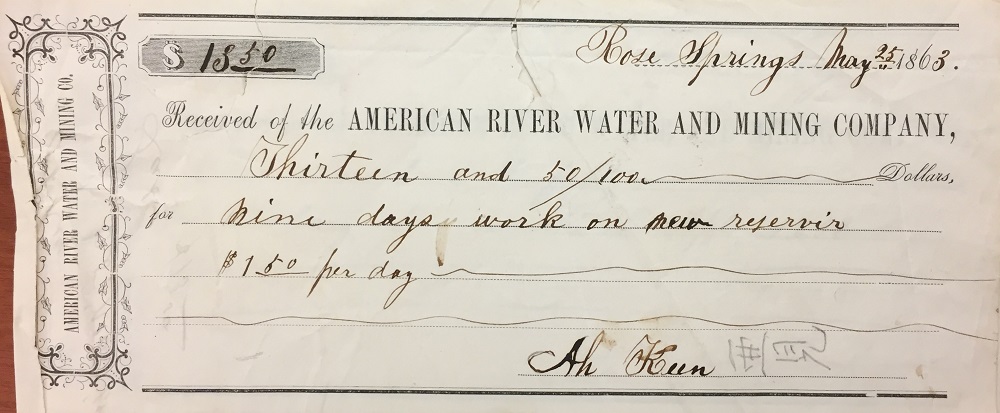

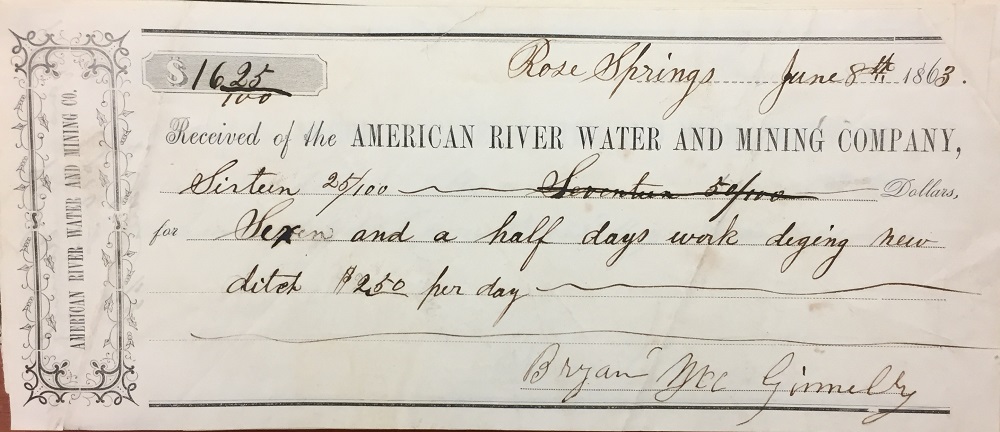

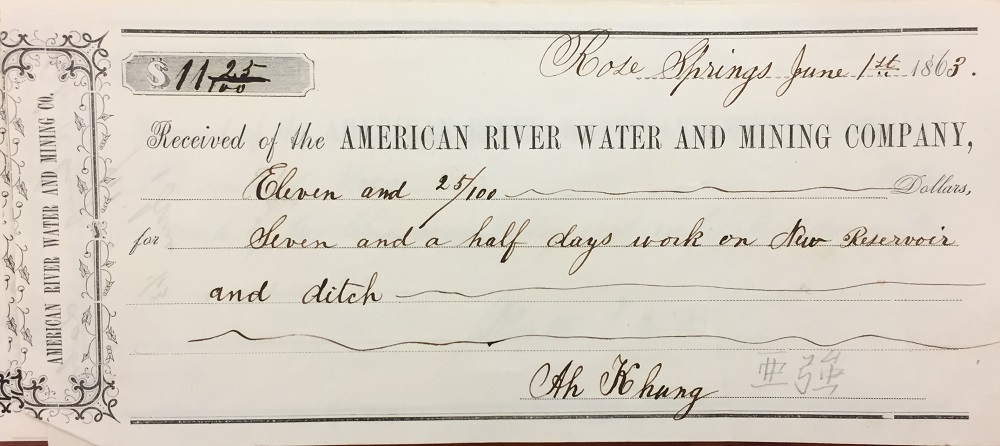

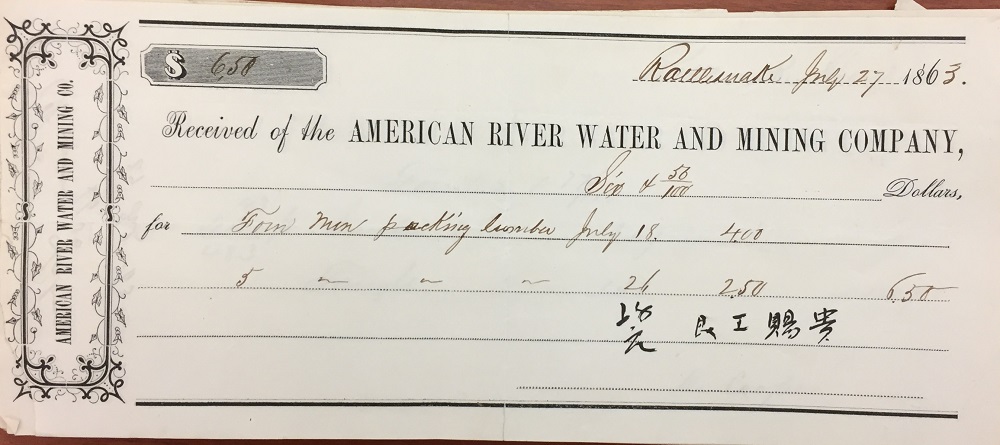

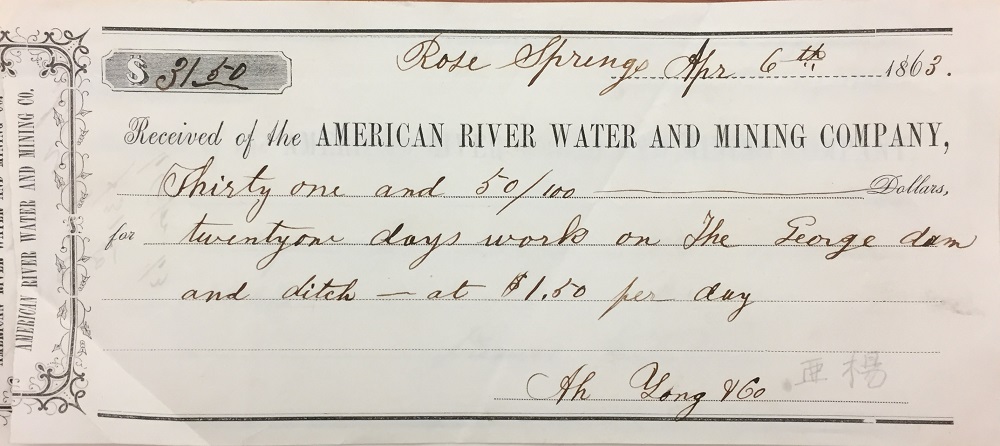

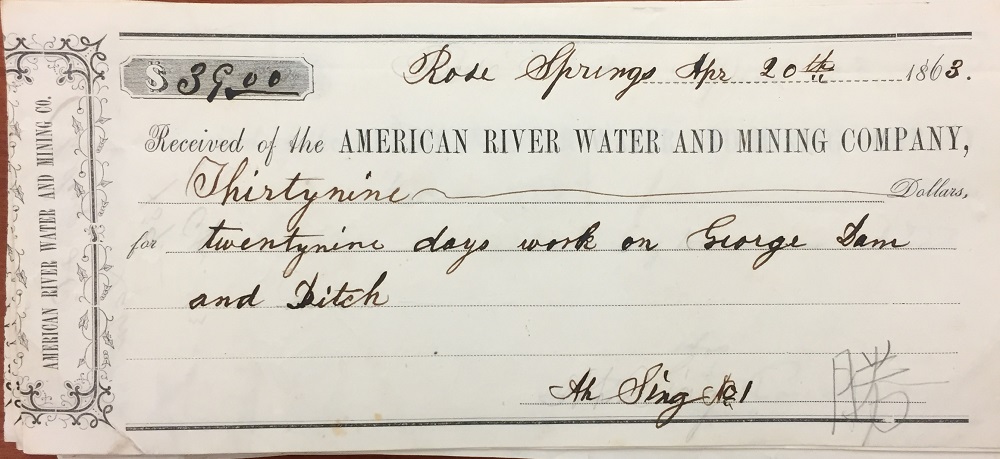

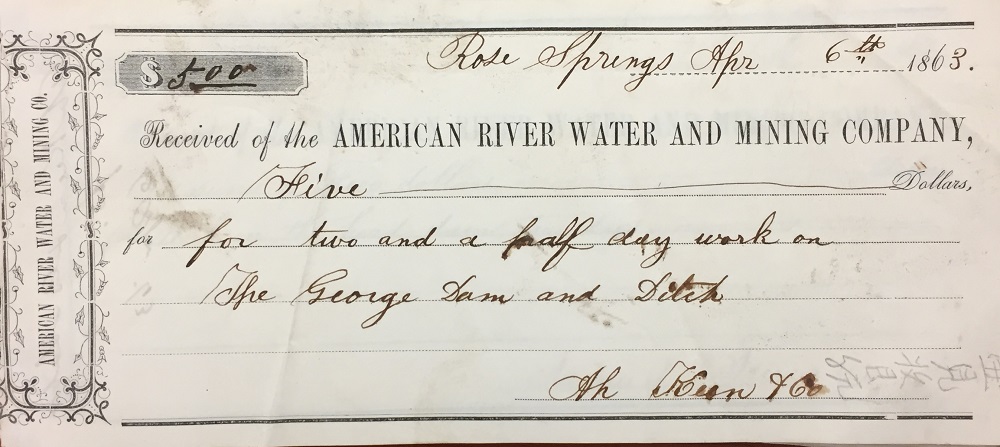

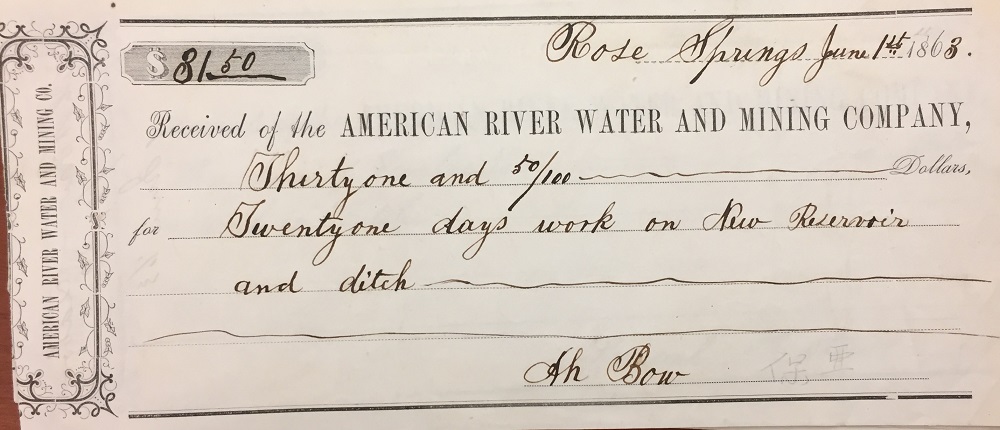

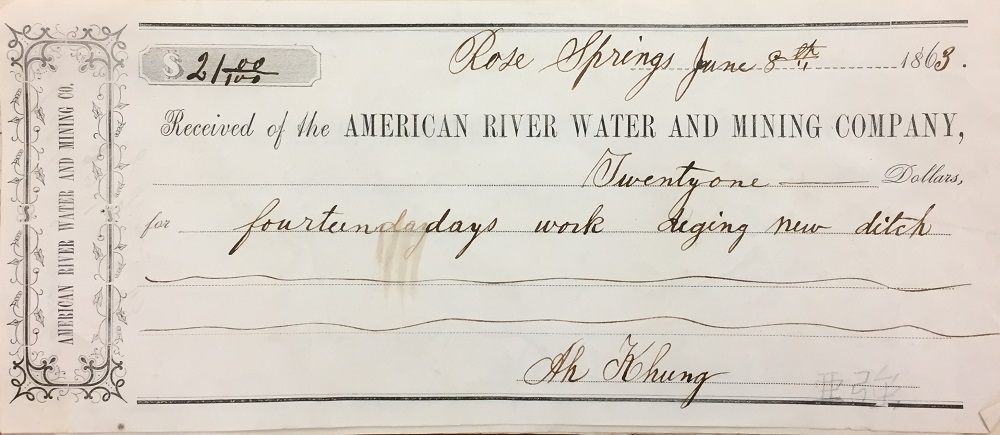

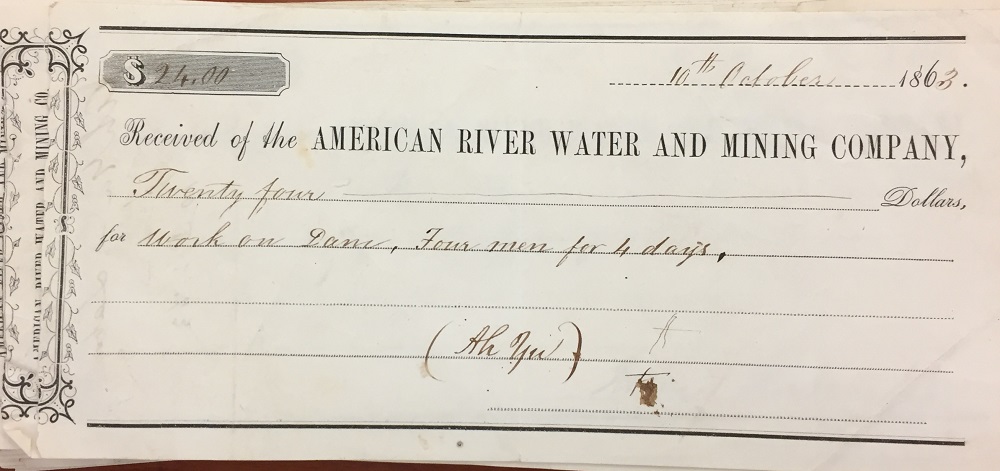

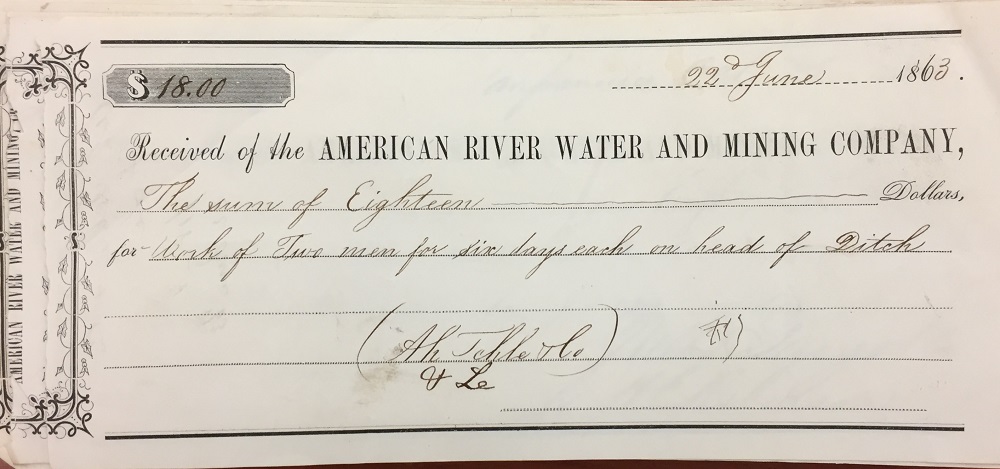

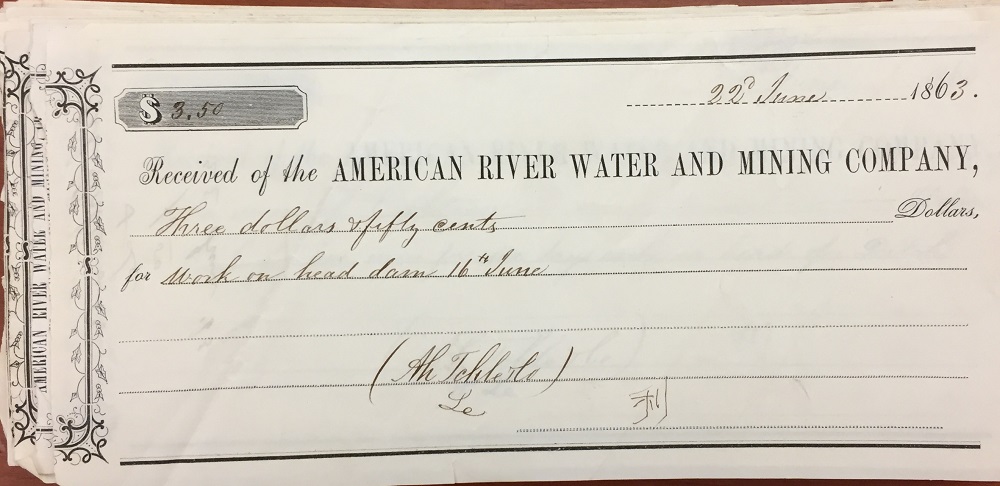

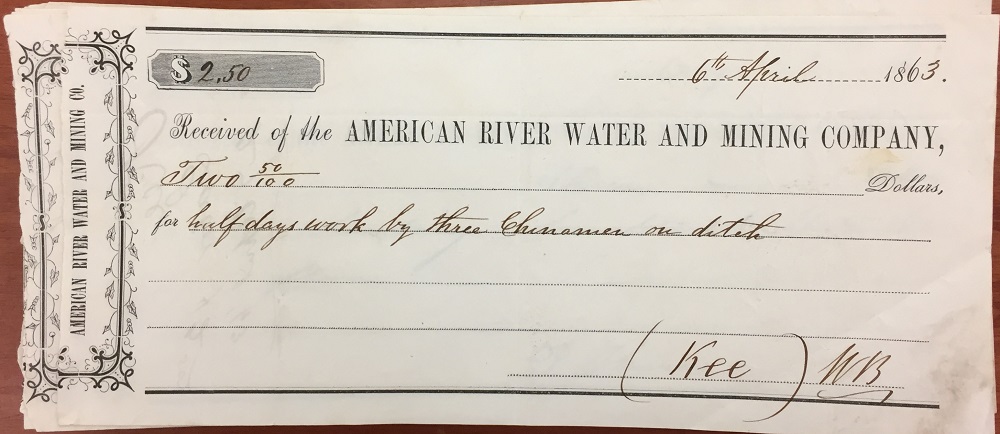

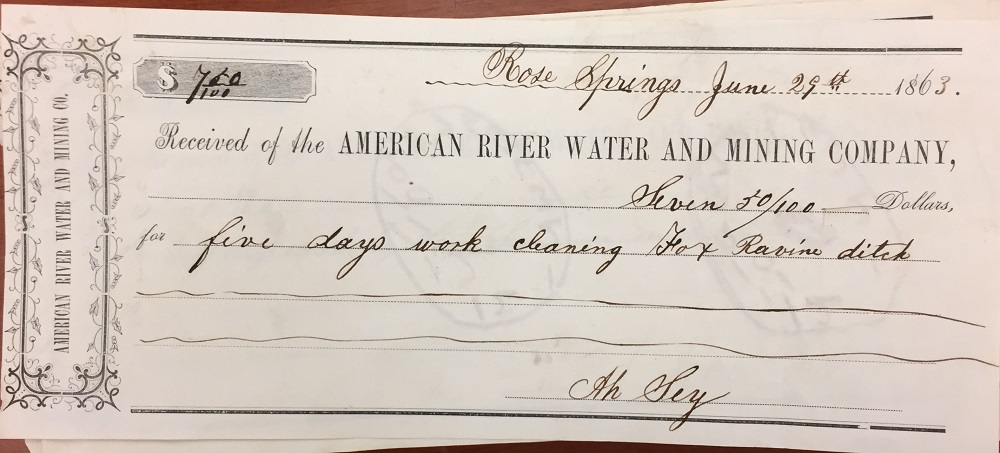

The payment receipts were printed with only nominal fields such as the date and dollar amount. It was up to the issuer or Treasurer to fill in specific information such as the place and description of what the payment was for. The North Fork Ditch, for the purposes of water collections, was divided into divisions such as Rattlesnake Bar, Horseshoe Bar, Doton’s Bar, Carrollton, Rose Springs, Slate Bar, and Beal’s Bar. Usually, the division or district where the labor occurred was noted on the receipt. It appears that the recipient was to sign their name affirming they had received the payment.

Of the 67 wage payment receipts, 28 were identified as being for Chinese labor. The identifier was either from the description or signature of the recipient. Several of the payment receipts have Chinese characters next to the anglicized name. A labor payment receipt could be for one individual or a group of men. Many of the men employed on a casual basis to work on the North Fork Ditch were local miners.

The description within the receipt also provided information on the wage rate. For white laborers, the daily rate was $2.50. Chinese labor was paid at $1.50 per man per day. I created a spreadsheet to compare the Chinese labor costs to that of white labor employed by the American River Water and Mining Company. Where the number of men and daily rate was not specifically mentioned, I imputed the daily rate by the total dollar amount. For example, Ah Sune was paid $13.50 for nine days work on cleaning out the Fox’s Ravine ditch in the Rose Springs district. Nine days times $1.50 per day comes out to $13.50.

The total dollar amount for the Chinese labor was $427.50. From my calculations, the wage receipts represent 288 labors days. If the Chinese would have been paid at a rate of $2.50 per day, the total wages would have been $720. By paying a lower wage to the Chinese, the American River Water and Mining Company saved $292.50.

For a comparison, I calculated 124.5 labor days for white labor. At $2.50 per day, the total wages for white labor tallied $311.25. The actual total dollar amount paid to white labor from the receipts was $313.13. The small discrepancy may be from the payment to Michael Kelly where it was noted that he also employed some Chinese laborers on the job.

What is interesting is that even though there were more payment receipts to white labor, Chinese labor accounted for more than twice the labor employed, 288 days versus 124.5 days for white labor. Most of the Chinese employment was for manual labor such as digging the ditch, cleaning, and earthen wall repair. The receipts for white labor include some receipts for skilled labor such repairing wooden flumes or bridges. However, when the wage receipt was clearly for manual labor, such as digging a ditch, the white labor was always paid $1.00 more per day than their Chinese counterparts.

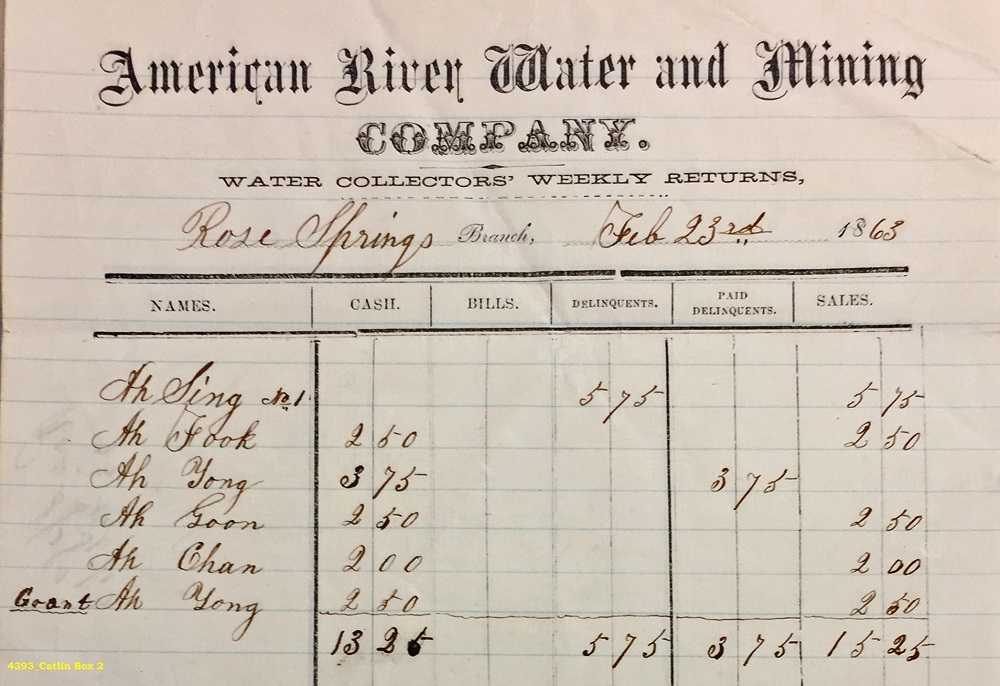

Chinese Miners Water Purchases form the North Fork Ditch

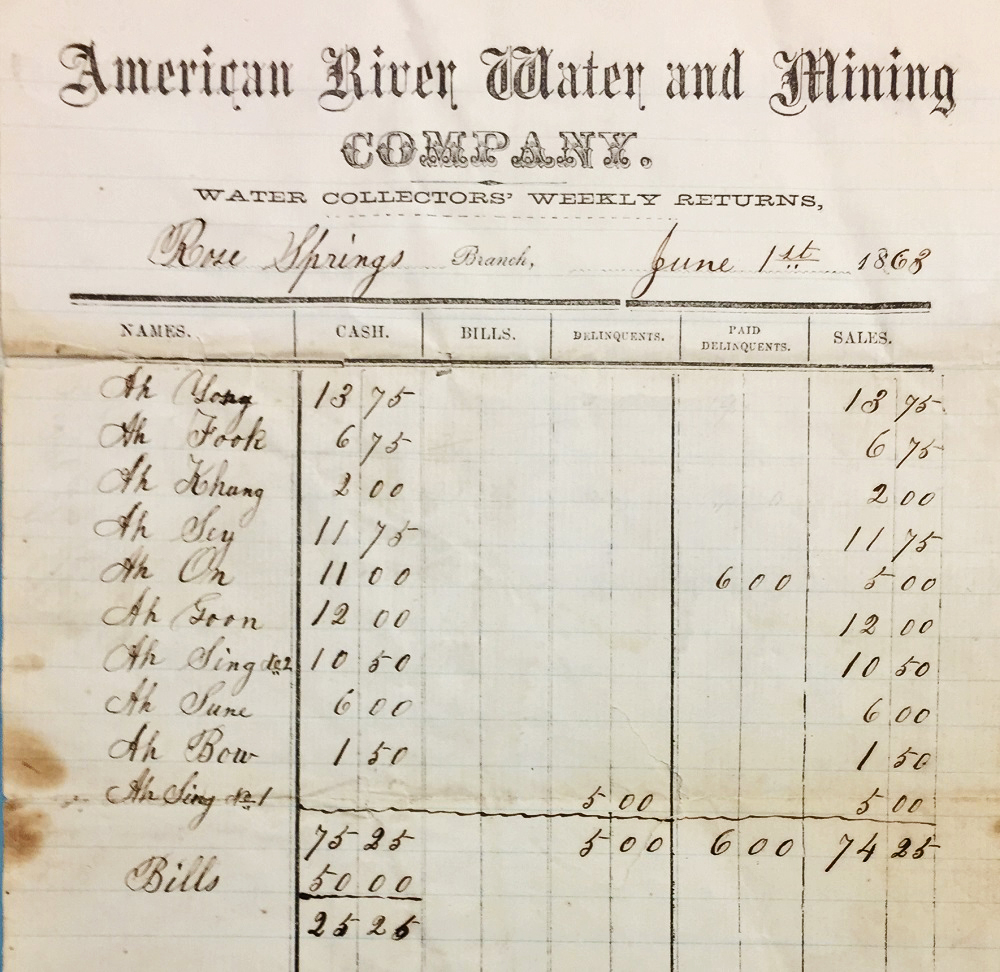

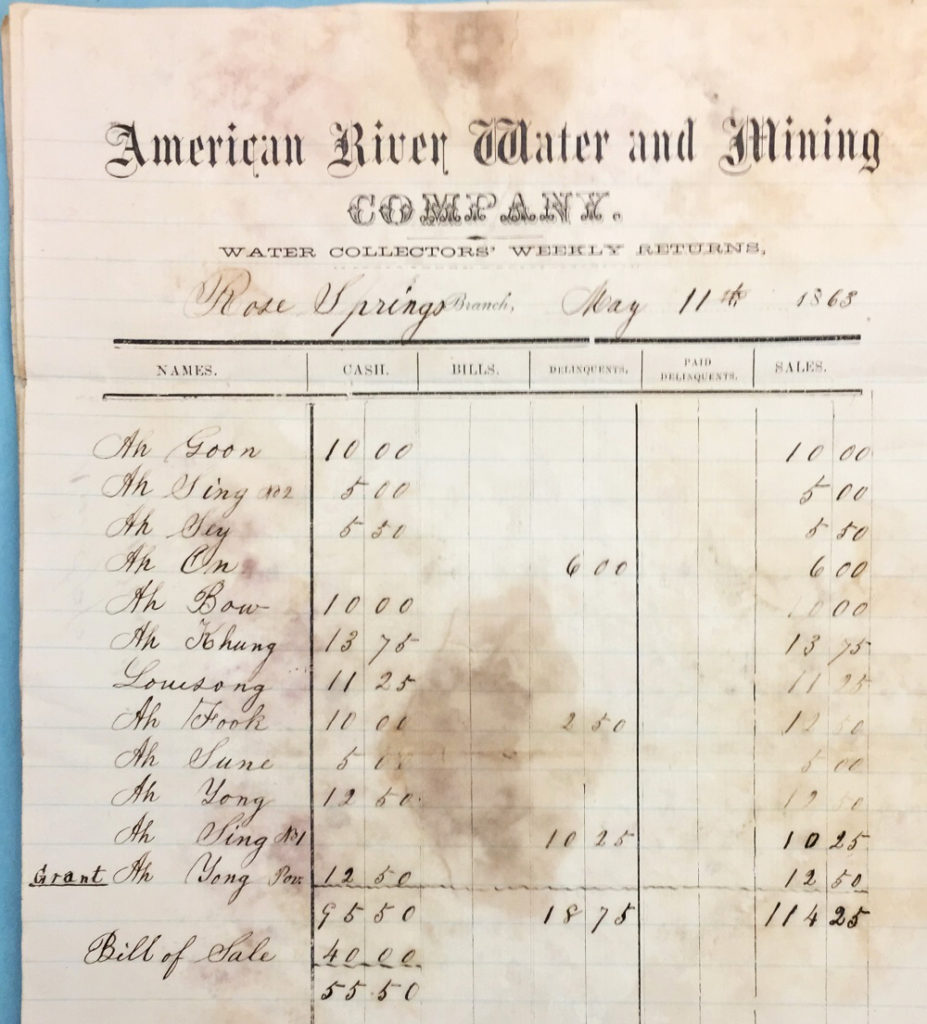

The next batch of documents dealt with water sales. The water collection reports were filled out by the water agents assigned to a specific district or division. To conserve cash, the American River Water and Mining Company eliminated some of the water agents and assigned some water agents to two districts. The collections were done on a weekly basis and only a tiny fraction of the collection reports survive at the Huntington Library in the Catlin collection. Specifically, there are reports from 1856, 1857, 1858, 1859, 1863, and 1868.

Even though the water was sold by the miner’s inch (approximately 11.2 gallons per minute for a 24-hour period), the early collection report only listed sale amount. Consequently, we don’t have a good sense of how much water, by volume, was used by specific miners. Sometime after 1863, the collection reports include volume amount and whether the water was being used for mining or irrigation. As mining declined, the water collection reports show increased sales for irrigation for orchards and ranches in the service area. The water consumer was identified by their name, mining claim, or company.

If a water consumer was not present when the water agent came by on horseback to collect the weekly water bill, the water charge was noted as being delinquent. Of course, it’s possible that the consumer did not have the cash to pay the water charge. It was noted if the consumer paid on a past due or delinquent amount. In the review of the water collection reports, I only found a couple of Chinese consumers who were noted as being delinquent.

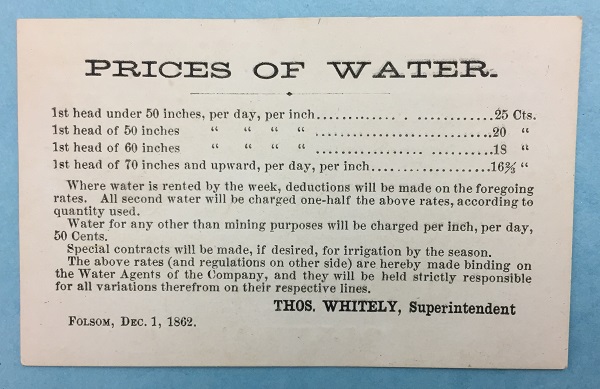

There is no indication that Chinese water consumers paid more for water than white miners. In 1863, published the water rates that reflected a decreasing cost per miner’s inch as consumption increased for mining purposes. Irrigation water was a flat $0.50 per inch per day.

The real historical treasure was the water collection reports for 1863, the same year as the wage payment receipts. In particular, water sales to miners in the Rose Springs division of the North Fork Ditch. Many of the wage payment receipts issued to Chinese men were for work in the Rose Springs area. Several of the Chinese men employed by the American River Water and Mining Company were also working mining claims in the Rose Springs district and on other parts of the American River.

Of the Chinese men paid for their labor on the North Fork Ditch, Ah Sing, Ah Khung, Ah Bow, Ah Yong, Ah Sune, Ah On, also purchased water from the Rose Springs branch of the North Fork Ditch. The water collection reports show a steady increase in Chinese miners purchasing water from the North Fork Ditch. For example, at Sailors Bar in November 1857, water was sold to 17 individuals. Of those miners, six of them were Chinese. In October 1858, one year later, there were 14 individuals purchasing water and 12 of them were Chinese.

From the water collection reports, 1863 had the highest concentration of Chinese men buying water mining and other purposes. Of course, the United States was in the midst of a Civil War and the Central Pacific Railroad was building their part of the Pacific Railroad to Utah. There were plenty of opportunities, patriotic and entrepreneurial, to earn money other than mining. The return on placer gold mining had greatly diminished in the late 1850s from the early Gold Rush of the early 1850s. Some miners were only washing $1 to $2 per day in gold dust. Consequently, a chance to earn $1.50 per day for equivalent hard work was not unwelcome.

The last year of the water collection reports, 1868, still shows a solid Chinese population of men mining and farming. What is notable is that, overall, at least for 1868, there were fewer consumers for the North Fork Ditch water. It appears some districts had a loss of approximately half of the consumer base in 1868 compared to water collection reports from before 1860. Chinese residents were also diversifying buying water for mining and to irrigate crops. What the water collection reports show was that until at least the late 1860s there was population of Chinese men who called the Rose Springs region home for mining and farming. Today, the area is part of Granite Bay in Placer County and encompasses Folsom Lake Estates and the Granite Bay Country Club, and north to Miner’s Ravine creek.

Another strong flooding event in 1867 again severely damaged the North Fork Ditch dam, canal, and flumes. The American River Water and Mining Company facing a flood of debt decided to sell the water system. The Board of Trustees would accept an offer from George Reamer in 1870 to purchase the North Fork Ditch for $10,000.

The Catlin Papers at the Huntington Library consists of over 2,000 documents. A good portion pertain to the American River Water and Mining Company. This little incomplete set of bookkeeping documents, trash to most people, provides a small record of the life of Chinese men along the American River in the 1850s and 1860s.

Below are some more of the labor receipts for Chinese labor. It is not a complete set of the records.

Attached are the spreadsheets I used to review the labor receipts and water collection reports of the American River Water and Mining Company.

ARWMC Payment Receipts worksheet

1863 labor payment receipts for work on the North Fork Ditch, American River Water and Mining Co., showing Chinese labor in Placer County.

ARWMC Water Collections

North Fork Ditch water sales collection weekly reports, incomplete, for years 1857 - 1868, showing water sales to Chinese miners in Placer and Sacramento counties.