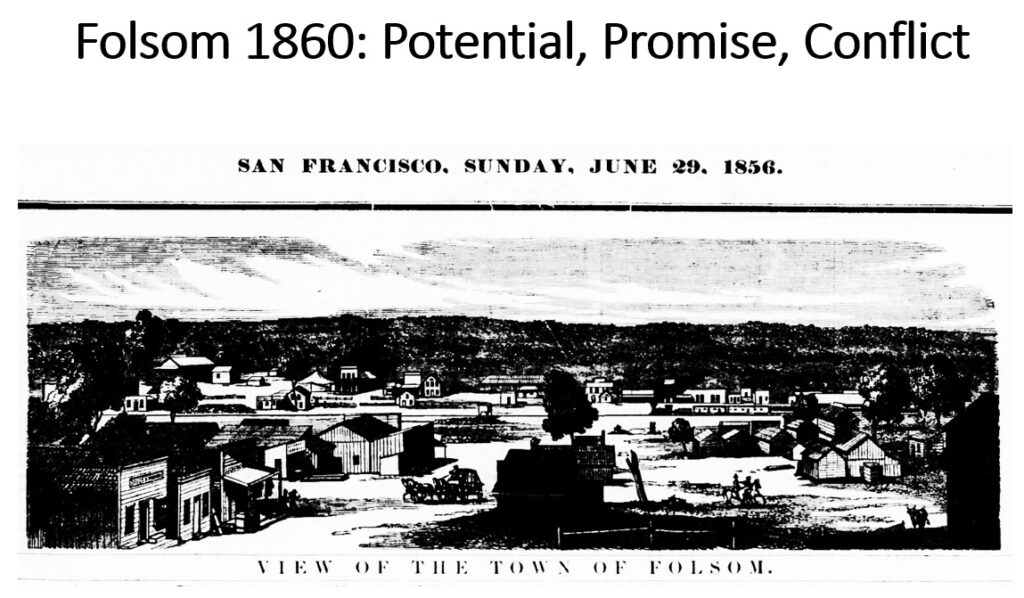

The town of Folsom in 1860 was full of potential and people from all over the world. The town and surrounding region had water from the Natoma Ditch, railroads, a large mining industry, and plans for a pleasant village with preparatory school. Competition for the natural resources would unfortunately lead to a clash between cultures resulting in mob violence against Chinese immigrants.

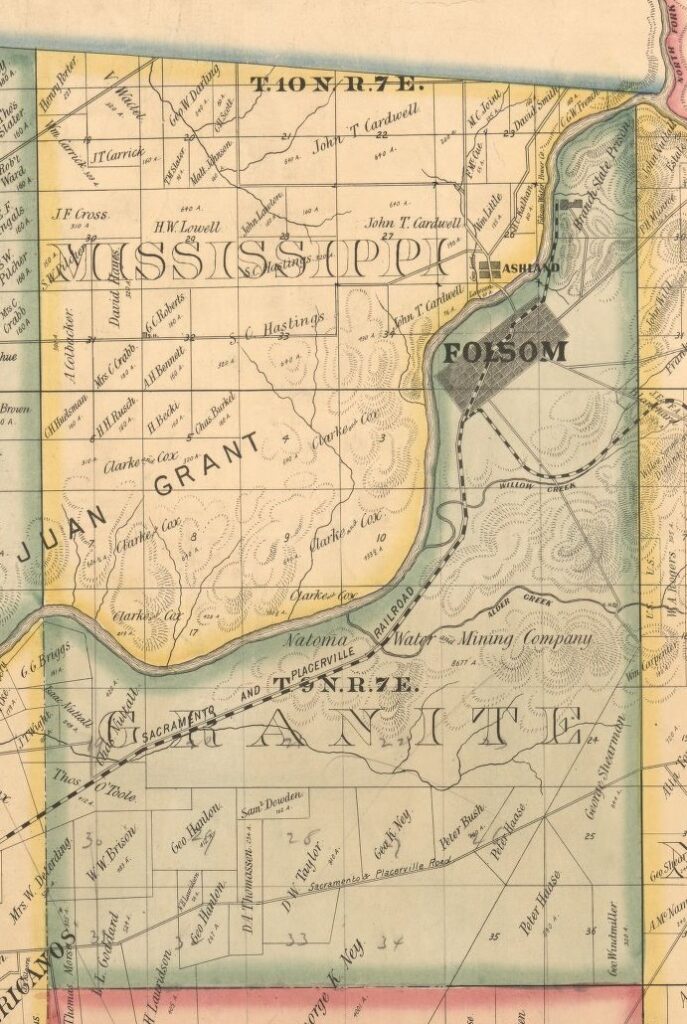

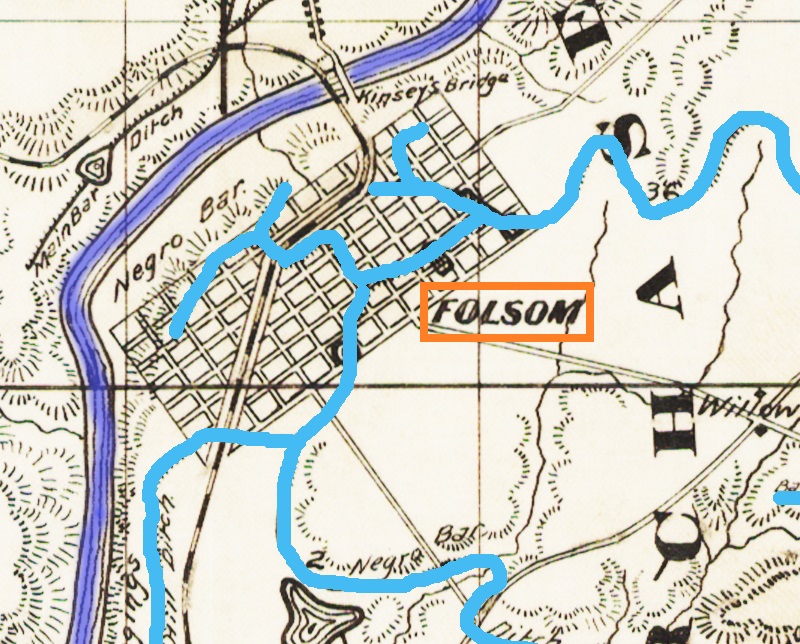

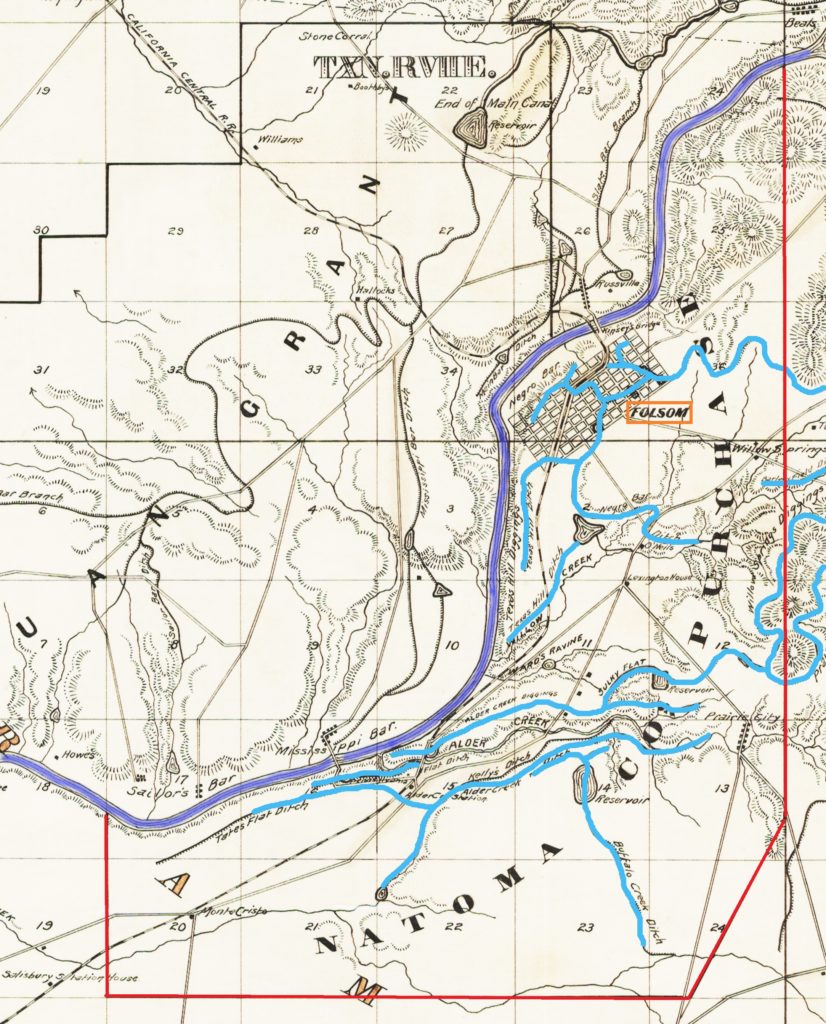

Central to the success of any town or region are the individuals who inhabit the area. The census of 1860 is a snapshot of the people who lived in and around the town of Folsom. Formerly known as Negro Bar, until the Sacramento Valley Railroad and the death Captain Joseph L. Folsom in 1855 spurred the town grid to be renamed Folsom, was located in the township of Granite.

1860 Census Records For Folsom, Granite Township, Sacramento County, CA

Because the census records don’t specify which dwelling or family was located in the Folsom town grid, I transferred all of the 1860 Granite Township records into a spreadsheet. The Granite Township census is comprised of 50 pages recording 552 dwellings and 1,956 residents. Granite Township encompasses approximately 27 square miles with the northern boundary being the American River.

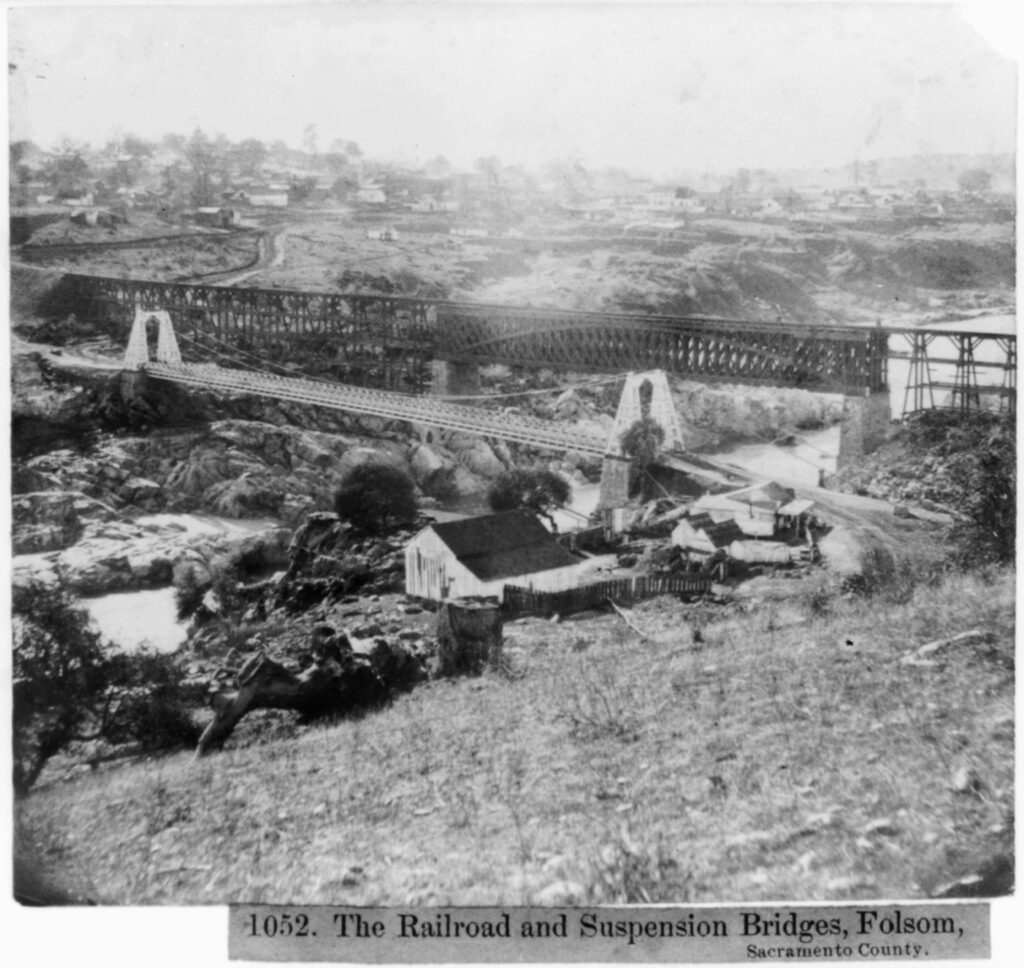

In 1860, Folsom was seen has having a tremendously bright future to rival Sacramento. The Sacramento Valley Railroad arrived in town in 1856. The California Central Railroad had completed a large wooden trestle bridge over the American River on its way to Roseville, Lincoln, and Marysville. There were plans for another railroad, the Sacramento, Placer, and Nevada, from Ashland, on the northside of the river, up to Auburn.

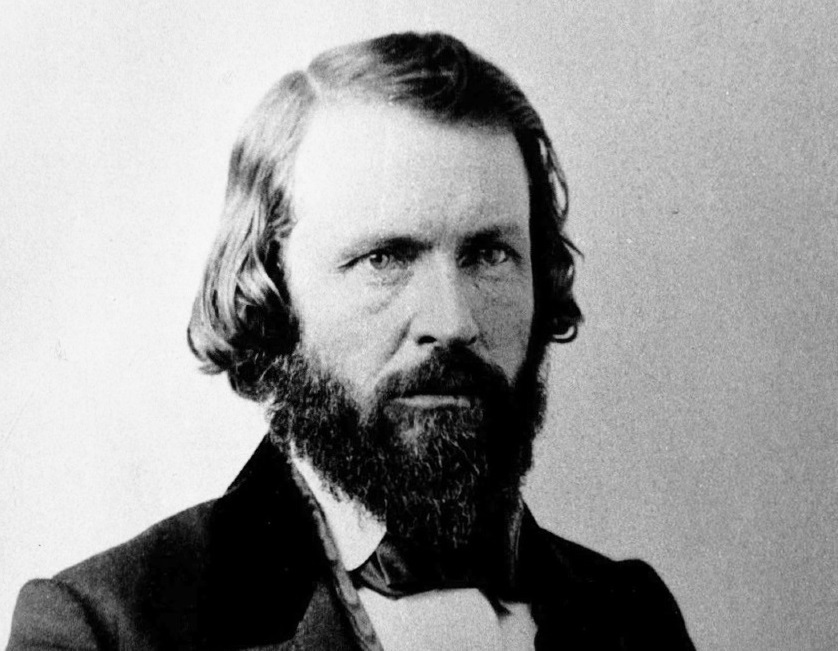

Folsom also had a network of water ditches from the Natoma Water and Mining Company that supplied water to residents, business, farmers, and the important mining industry. In addition to the town grid laid out by Theodore Judah, there were plans for preparatory school named the Folsom Literary Institute. Many of the prominent men associated with mining and the water company lived in Folsom such as Amos Catlin, A.T. Arrowsmith, C.T.H. Palmer and others.

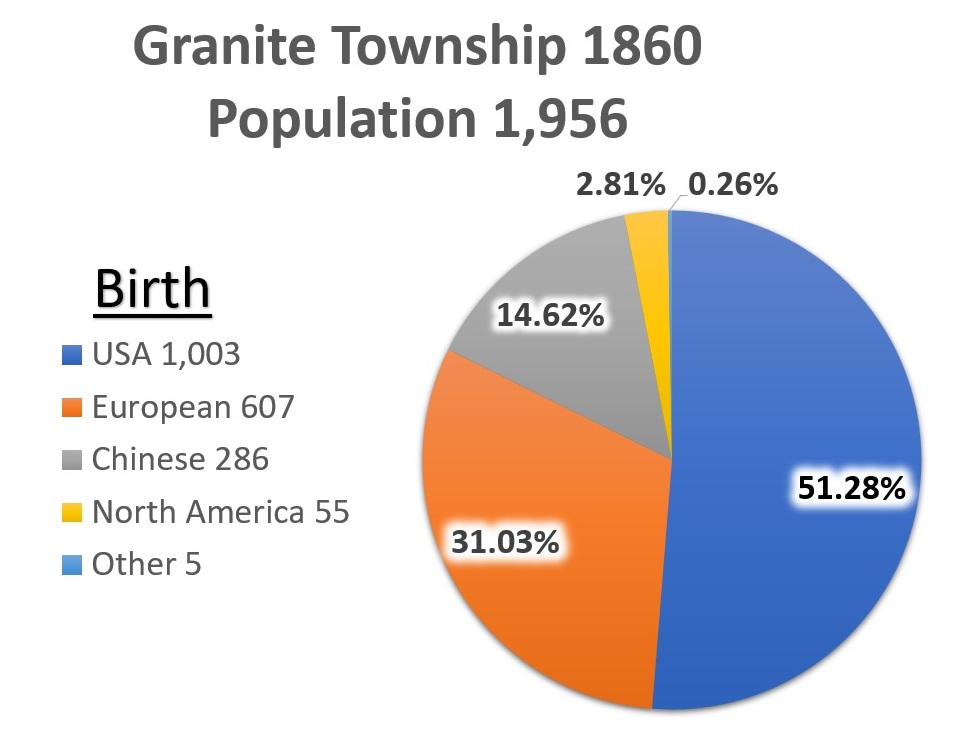

Similar to other California communities of the mid-19th century, Granite Township had a diverse population. Of the 1,956 residents, only slightly more than 51 percent were born in the United States. People of European birth comprised 31 percent of the population and Chinese made up almost 15 percent of the residents. People born in Canada and Mexico were less than 3 percent.

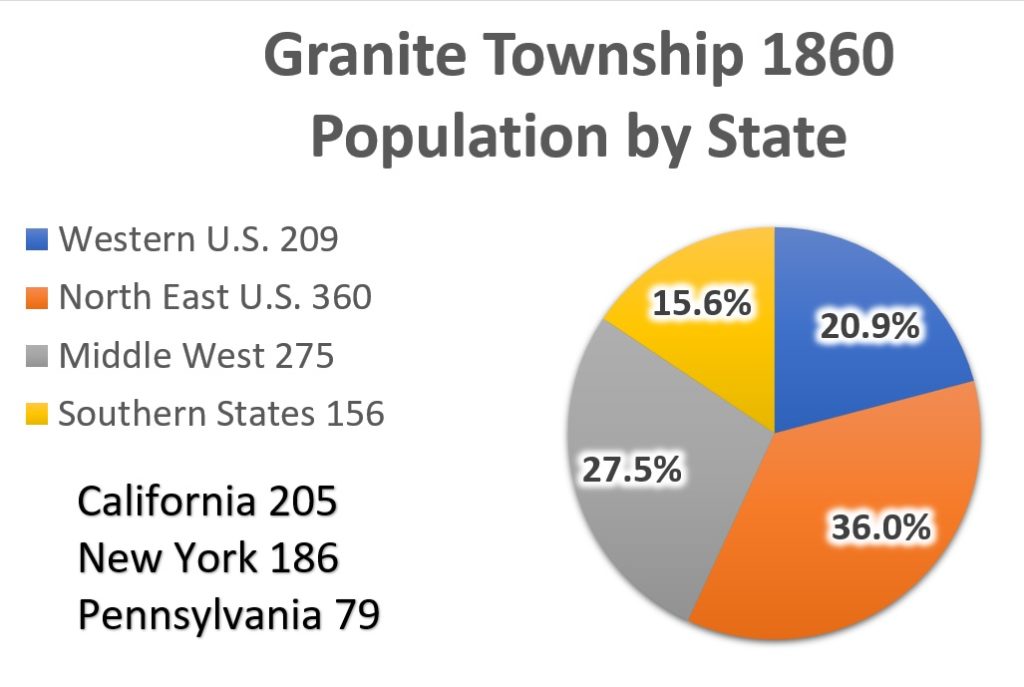

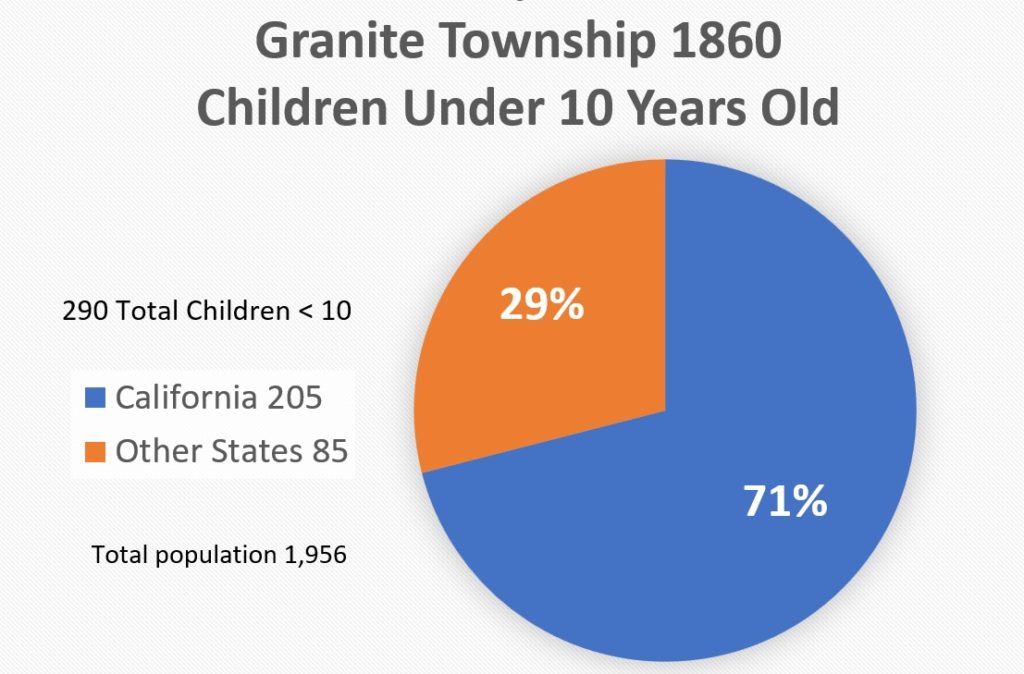

A large share, 36 percent, of the U.S. born residents came from in the northeast such as New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania. The middle west states contributed 275 people and the southern states, where slavery was legal, accounted for close to 16 percent of the population. There were 209 individuals born in the western states and 205 of those were born in California. Virtually all of the California born individuals were under the age of 10.

Of the children under 10 years of age, 71 percent were born in California.

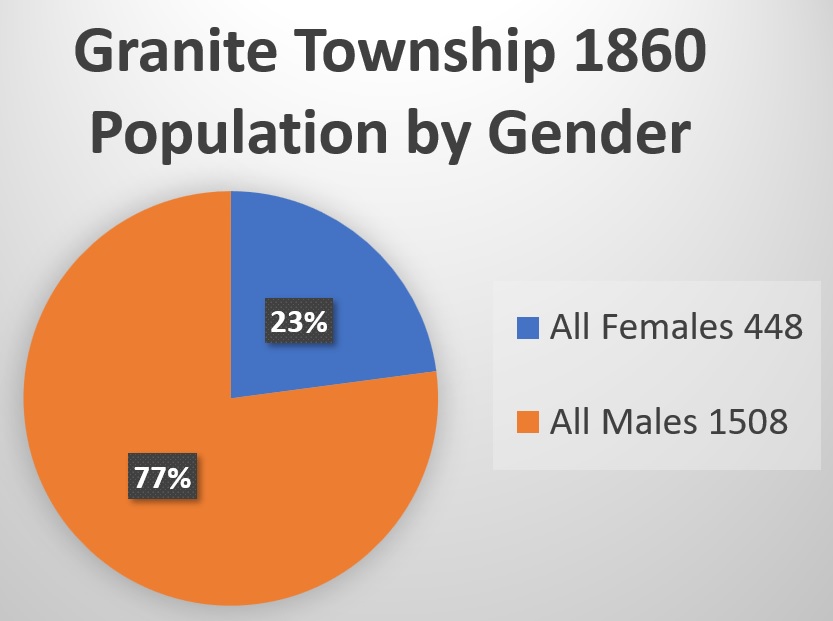

Males naturally comprised a greater percentage of the population, 77 percent, as it was mainly men who made the arduous journey to California to mine for gold.

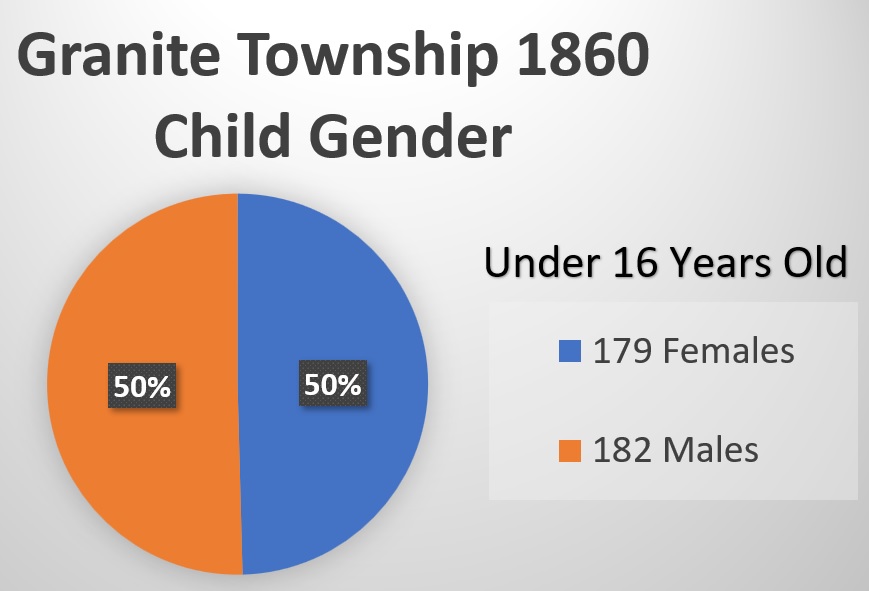

Once the men were settled, married, and started having children, we see the gender distribution more equalized. Roughly half the individuals under the age of 16 were female.

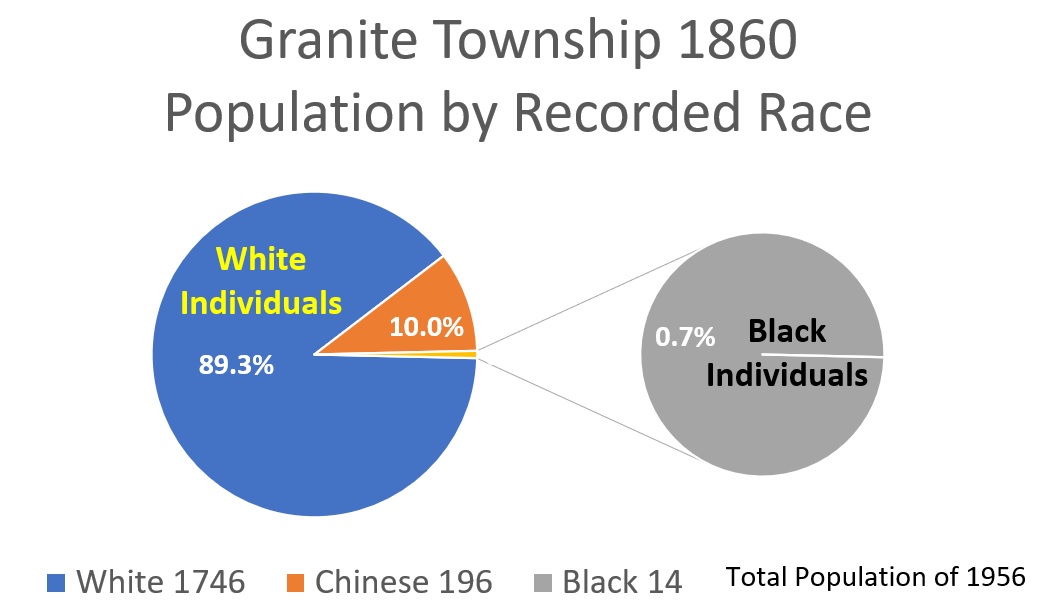

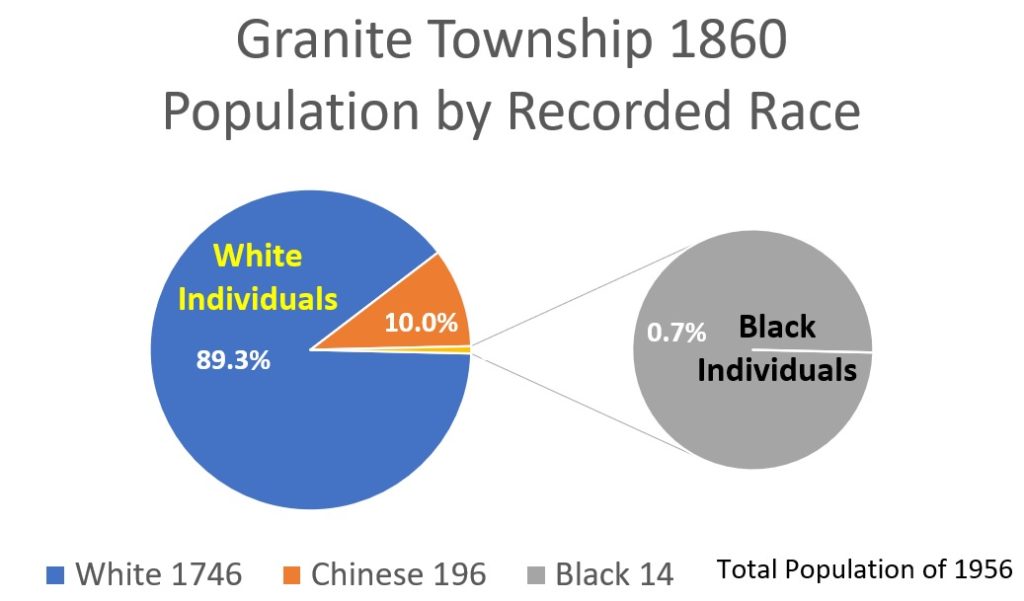

It was no surprise that the majority of the population was recorded as white. The census forms emphasized the race to be counted as either white or colored. It seemed to be left up to the census recorder to make determination of the individual’s race, white, black, or something else. On the census pages for Granite Township, the color field was left blank unless the recorder indicated Black or Mongolian. Consequently, 89 percent of the population was recorded as white, 10 percent were Mongolian or of Chinese descent, and less than 1 percent Black.

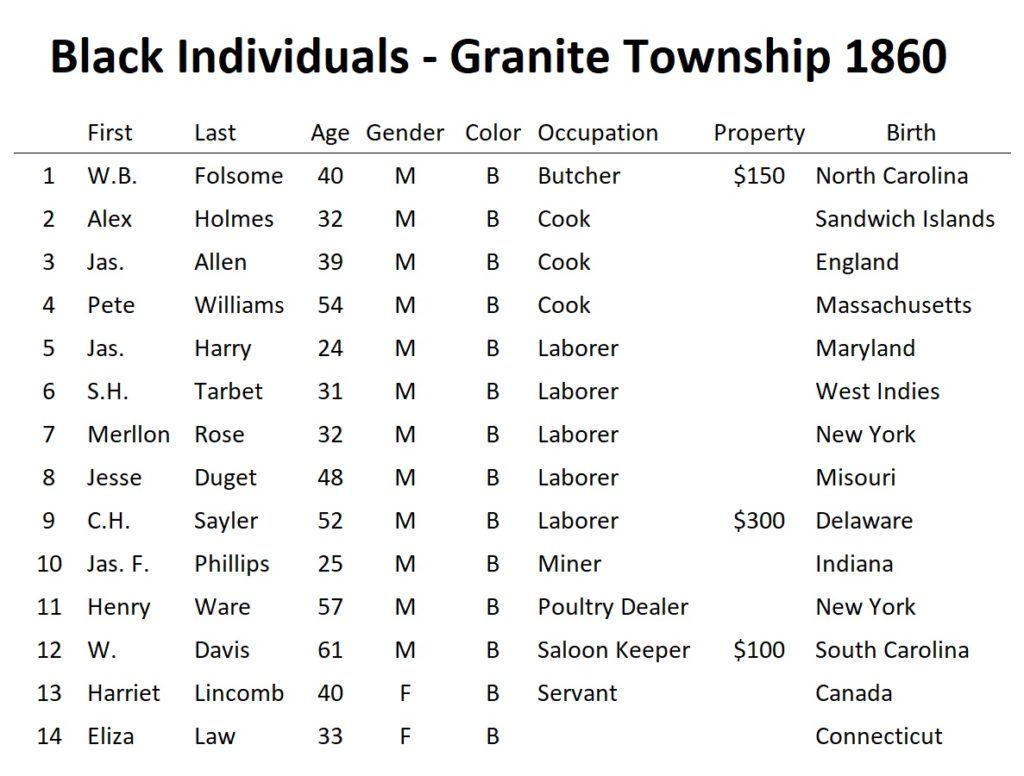

There were 14 people recorded as being Black, 12 men and 2 women. Only one individual identified as a miner. The other individuals listed occupations as butcher, cook, laborer, poultry dealer, saloon keeper, and servant. Most of the entries for the Black individuals are grouped on one page early in the census pages. If the census recorder began his work in the northern part of the township, he may have encountered this group of Black individuals presumably around the Negro Bar area. Regardless, the Black residents were born in a variety of different states. Four stated they were born outside of the U.S. and indicated Sandwich Islands (Hawaii), England, West Indies, and Canada.

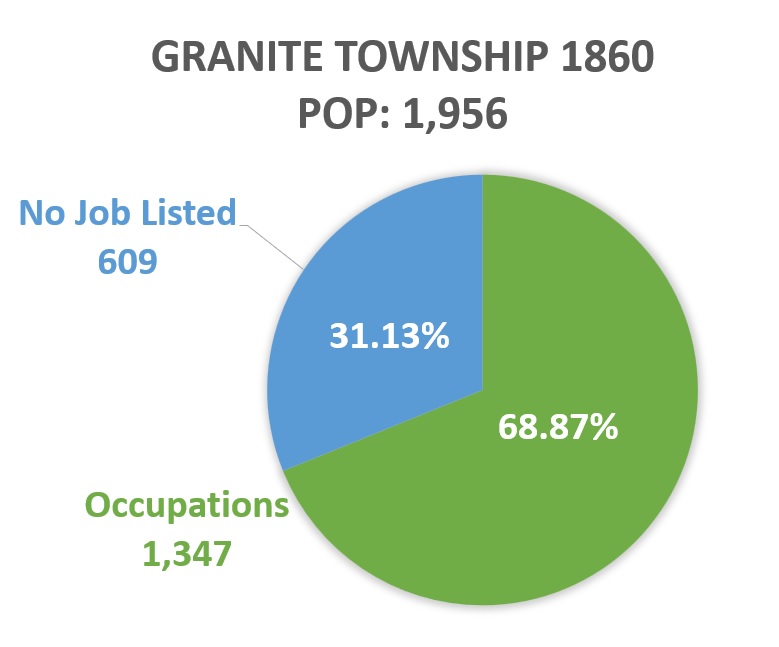

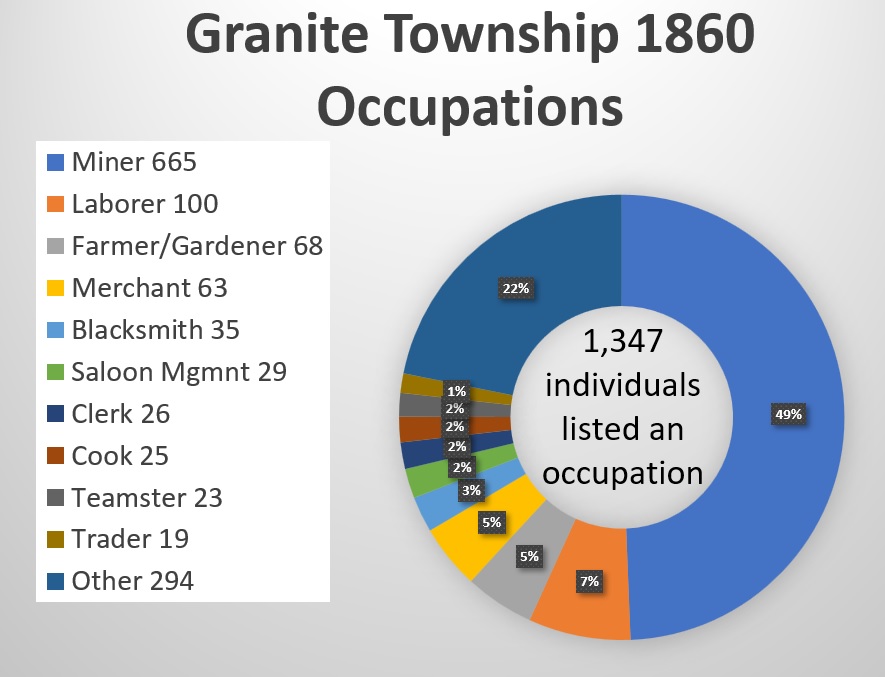

It is clear from the listed occupations that mining continued to be an important generator of income in 1860. Of the 1,347 who had occupations listed, 665 reported mining as their primary occupation. The next biggest category was laborer with 100 individuals recorded. The relatively large number of laborers tracks with construction projects in Folsom from railroads to residential housing.

Similar to the mining industry’s prominence because of available water from the Natoma ditch system, farmers and gardeners were also common occupations. There were 68 individuals who identified as famers or gardeners. While I’m not certain that farmer and gardener were synonymous, the distinction seems to be derived from the individual’s origins with more foreign born men calling their occupation gardener as opposed to farmer. There were 63 merchants indicating the growing mercantile business in the town of Folsom.

A total of 35 men reported their occupation as blacksmith. This relatively high number of blacksmiths may be related to the railroad industry in town. There were only approximately 5 men who directly linked their occupation to the railroad such as railroad, agent, brakeman, or fireman. Also linked to the railroad were the 23 teamsters, men who hauled freight either to or from the railroad depot.

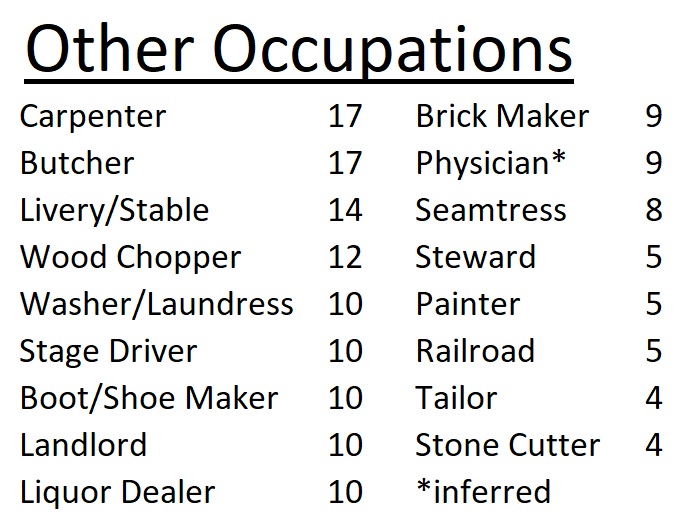

There were also numerous other occupations listed such as carpenter, butcher, along with boot makers and washer women. Wood chopper was the occupation of 12 men. Wood was the primary source of energy for heating and cooking. The cutting of trees would be one of the conflicts in the regions. An occupation I had not consider being in the region was brick maker. Brick maker was listed by 9 men who all resided near one another.

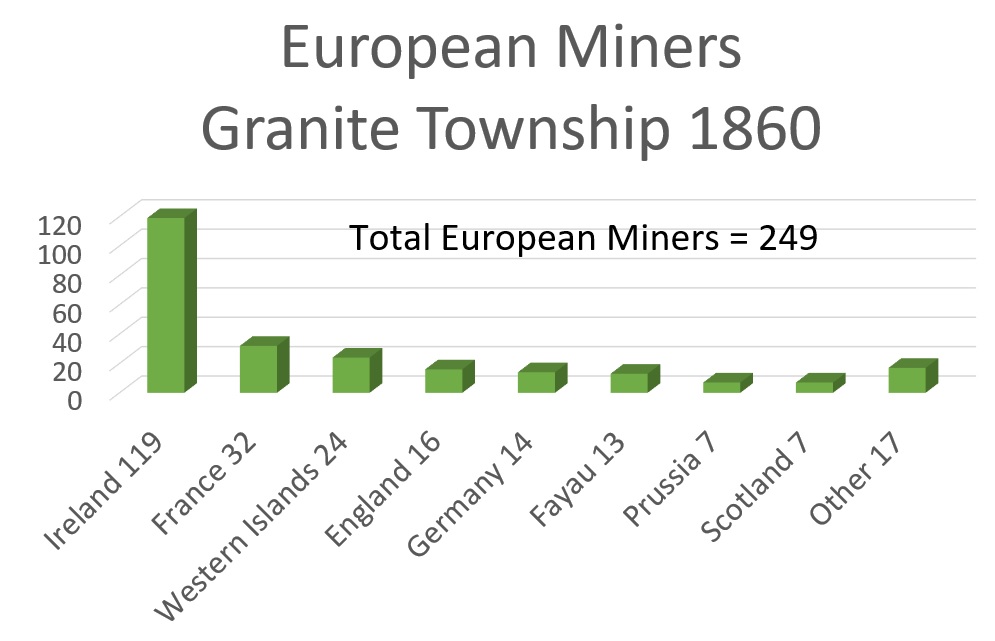

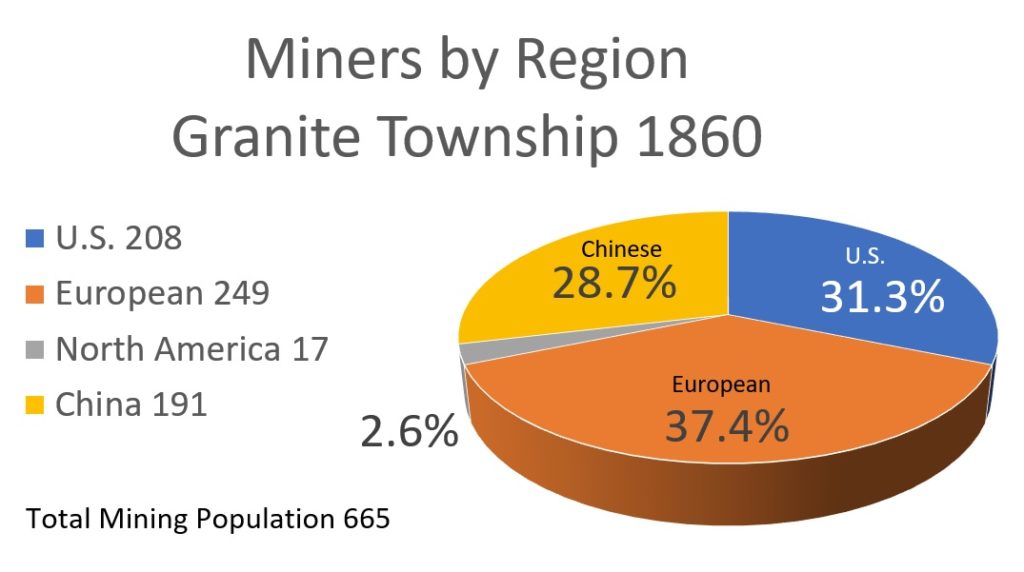

The mining industry was dominated by foreign born men. Of the 665 men listing their occupation as miner, 37 percent were of European birth and almost 28 percent were from China. Of course, it was primarily U.S. born men who comprised the gold rush of 1849. The initial gold rush wave of miners scoured the river beds of placer gold. The majority of mining in 1860 was the washing of high and dry ground for placer gold with water supplied by the Natoma ditch system.

The largest group of European miners came from Ireland, 119 men. However, some men were biased toward giving a region of birth that may not technically have been a country by today’s map. For example, 13 men reported that they were from Fayau that is a small region within France. Consequently, you could attribute 45 men being from France, 32 from France and 13 from Fayau. Similarly, the Western Islands is a cluster of islands off of the north western coast of Scotland. The men could have reported they were from Scotland, but chose Western Islands. Then, as today, a person’s region of birth can be a large part of the individual’s identity.

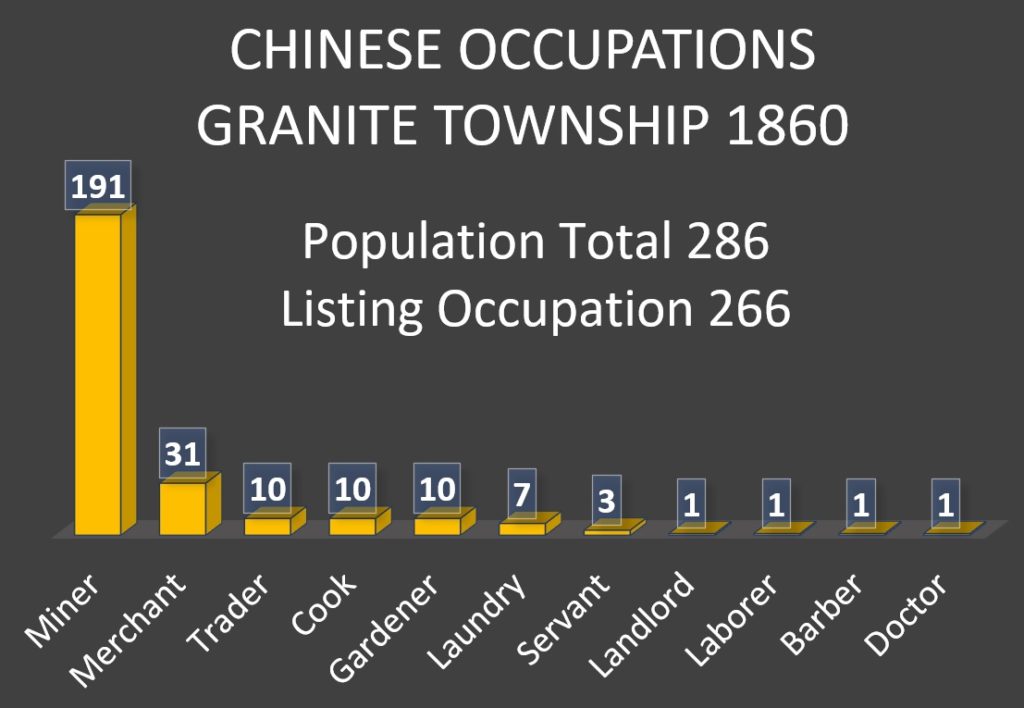

1860 Chinese Population of Granite Township

Except for one entry, there was never a specific geographic location from which the Chinese immigrants came from. On one page, the census recorder wrote what could be construed as “Cantin China.” Of the 286 residents of Granite Township in 1860 who were identified as being born in China, 191 listed their occupation a miner. The next largest occupation was merchant at 31. There were 10 entries each for the occupation of trader, cook, and gardener. Other occupations listed by the Chinese were laundry, barber, and doctor.

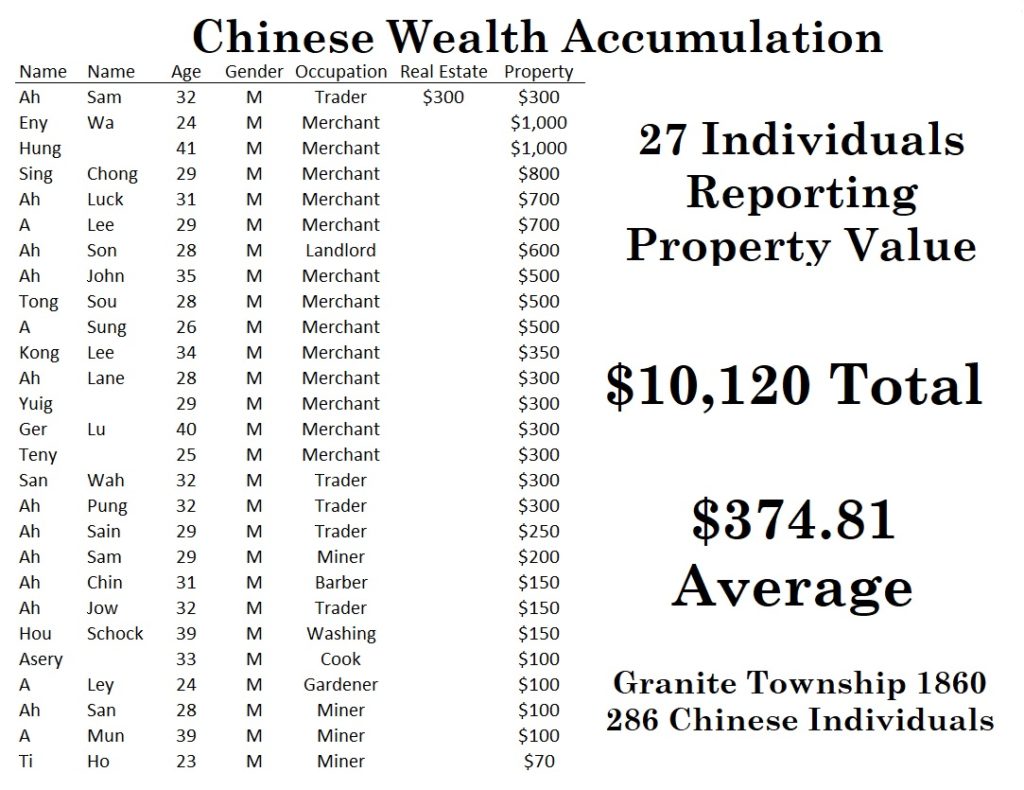

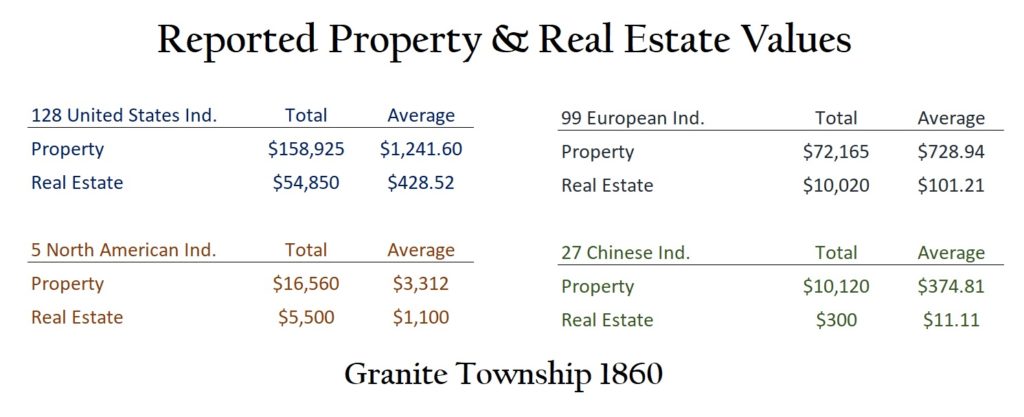

Despite the additional burden of paying the foreign miners’ tax, 27 Chinese reported owning property. Most of the property value was clustered among Chinese who reported being either a merchant or trader. The total value of the real estate and property equaled $10,120. There is no way knowing if the property had enduring value such as inventory or tools, or if the property was a mining claim.

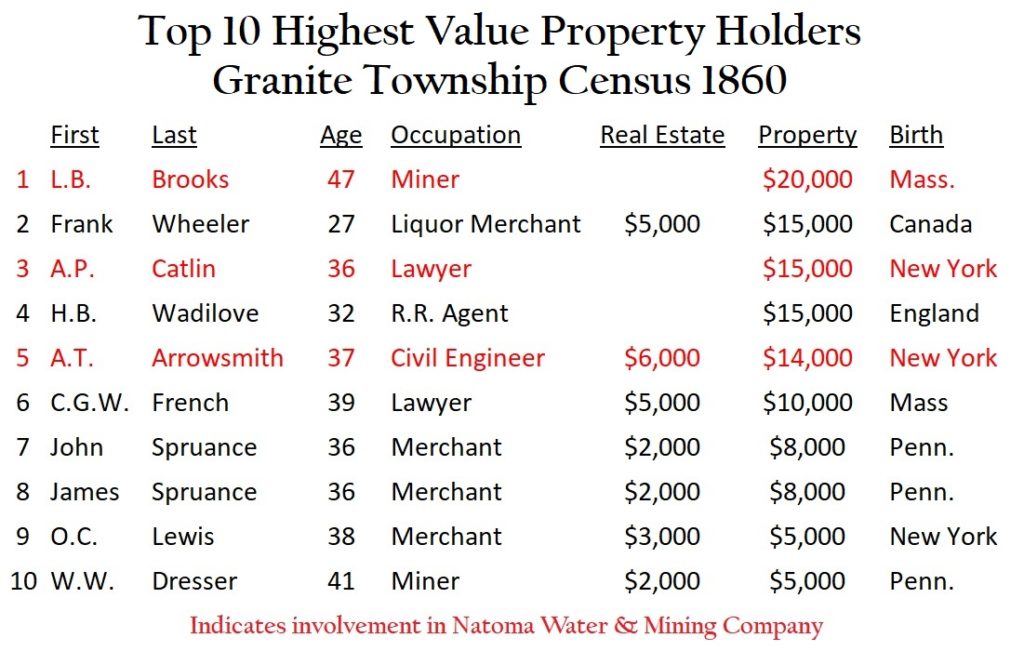

Because the dollar values of property and real estate cannot be fixed, interpreted, or adjusted for inflation, they are relatively useless. The important point is that the individual deliberately reported having accumulated some sort of property of value. Other individuals did report their real estate and property values, but we don’t know how they ascertained the value. For example, Amos Catlin, reported a property value of $15,000 and no real estate. However, Catlin was on the title of ownership for close to 20 percent of the lots in the town of Folsom. In short, we don’t know if the individuals were reporting the value of their property under the same rules of value.

If we assume the individuals were reporting the value of their real estate and property in a similar manner, we can compare Chinese wealth to other groups in Granite Township.

The largest holder of wealth in terms of real estate and property were individuals born in the United States. They reported $158,925 in property and $54,850 in real estate from 128 individuals. The next closest wealth accumulators were European individuals who reported $82,185 in combined property and real estate.

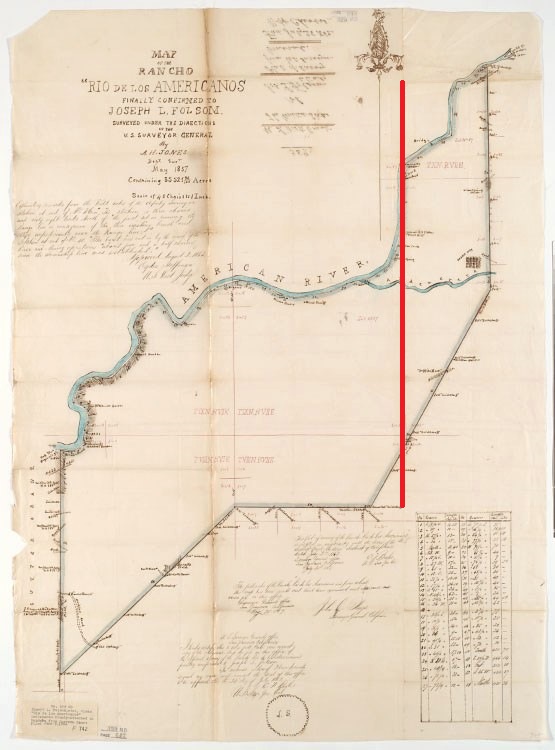

Close to half of the land in Granite Township was owned by the Natoma Water and Mining Company in 1860. The company’s land holdings excluded Folsom town lots and the railroad within their land title. Regardless, it was nearly impossible for many individuals to purchase land in Granite Township or a Folsom lot. Neither the Natoma Water and Mining Company of the Folsom estate, who controlled the Leidesdorff land grant, were selling their real estate in 1860. After the land grant map was approved by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1864, land began to be opened for sale. An individual could own a mining claim, but not the land the claim was staked to. Finally, we don’t know if the reported property and real estate values pertained to assets in Granite Township or another part of the state.

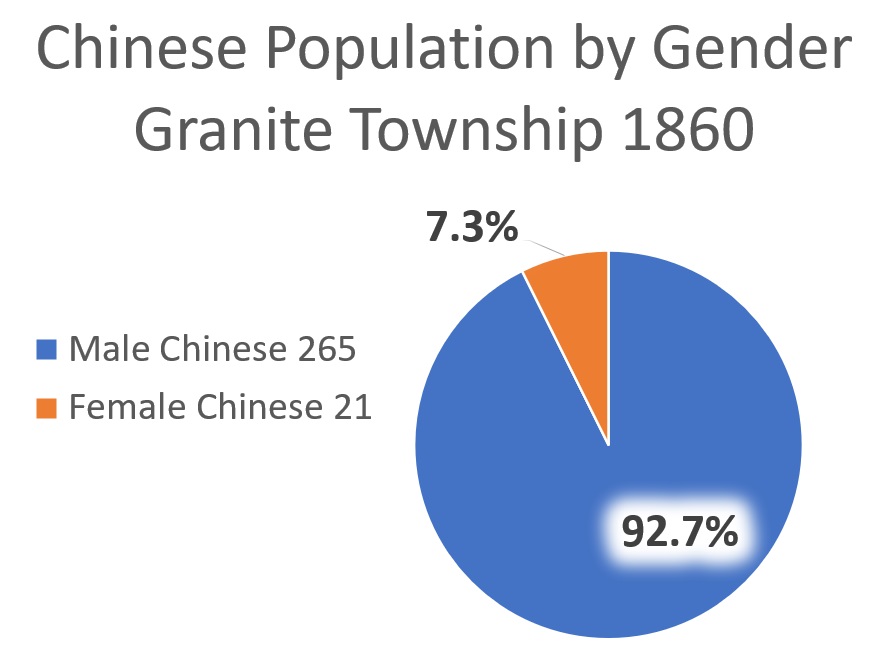

Whereas there are numerous instances within the census of European and U.S. born individuals marrying, there were no mixed-race marriages recorded between Chinese and other nationalities. In the Chinese community, 92.7 percent were male and 7.3 percent were female. There was only one record of a Chinese child. Wan Ho, a male born in California, was entered right below Ma Ho. The inference is that Ma Ho was the child’s mother.

Alder Creek Riot Against The Chinese

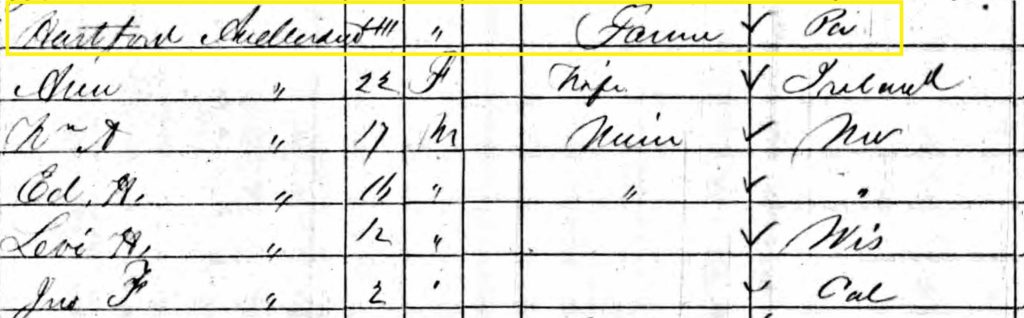

It was a surprise to enter the record for Hartford Anderson, age 41, a farmer from Pennsylvania, into the spreadsheet. Anderson reportedly instigated, promoted, and led a mob of men to chase Chinese from their mining claims and homes, destroying their property along the way in March 1858. The Alder Creek Riots, as the Sacramento Bee called it, was the result of a landownership dispute. At its heart, the conflict and marauding mob was a manifestation of the competition for natural resources in Granite Township.

The headline, sympathetic to the Chinese victims, from the Sacramento Union, March 6, 1858, announced Unlawful and Barbarous Treatment of the Chinese. As reported by Sacramento Union.

…a mob of about one hundred and fifty persons — mostly citizens of foreign birth — assembled near Alder Creek, in this county, for the purpose of expelling the Chinese from the mines in that vicinity. After being inflamed by speeches from one Hartford Anderson and Michael Wallace, and other leaders, and being well supplied with whisky, the mob marched in a disorderly manner over a circuit of about ten miles, driving the poor and inoffensive Celestials from their claims and houses, tearing up their sluices, razing their dwellings to the ground (in some instances burning them to ashes) scattering their goods, and beating and otherwise maltreating them.

About two hundred men were thus deprived of their homes and property; the poor, terror stricken creatures concealed themselves among the trees and chaparral. One object of the rioters was probably plunder, as we are informed that, in several instances, they took from the Chinamen their money. Another object was to possess themselves of the claims which these people had purchased from some of the very men who were engaged in inhumanly driving them off. It is to be hoped that there is sufficient virtue in the law to vindicate the sentiment of the community, which has been outraged by these lawless proceedings, and that the chief offenders may receive the just punishment which their shameful conduct merits.”

Sacramento Daily Union, March 6, 1858

The Sacramento Union also noted that through the foreign miners’ tax, Sacramento County was collecting approximately $1,200 per month from the Chinese miners. In letter to the Sacramento Union, Hartford Anderson denied being involved with the Alder Creek riots. He laid the blame for the violence and destruction on the shoulders of the Natoma Ditch Company. The violence against the Chinese, many of whom were customers of the Natoma water system, and accusations that the Natoma Water and Mining Company was to blame for inciting the conflict, pushed Amos Catlin, president of the water system, to respond.

In a March 10, 1858, letter to the editor of the Sacramento Union, Catlin laid out the foundation of the conflict. First, in 1857, Catlin had purchased 9,643 acres of the Leidesdorff land grant from the Folsom estate for $36,800. The land purchase encompassed the area where the Natoma Water and Mining Company system of water ditches crossed into the boundaries of the land grant.

Shortly after the purchase, the Leidesdorff land grant boundaries were contested. The U.S. Secretary of the Interior ordered a new map of the land grant be drawn and submitted. The point of contention was the eastern boundary of the land grant. Proponents of the new map argued that the eastern boundary of the land grant was roughly where Alder Creek entered the American River. If the alternate eastern boundary was confirmed, it would nullify most of Catlin’s purchase of the land grant as the land would be considered public land.

It was also in 1858, after Catlin had finalized the purchase of the property, that he initiated court action against Hartford Anderson and other wood choppers for illegally taking of timber from the property. Catlin argued that the trees that were being cut down were needed by the company for wood for the miles of wooden flumes the company utilized to deliver water.

Catlin, in his letter to the Sacramento Union, outlined another issue that was a sore point for some miners. A conspiracy theory had been generated that the Natoma Water Company favored the Chinese miners.

……reports have been industriously spread among the miners, by these defendants, to the effect that the Company intended to supplant the white miners and introduce the Chinese, by a gradual system of preferring the latter to the former in the distribution and sale of water.

Catlin went on to detail the misunderstanding.

There are only two Chinese claims upon the whole line of the branch which supplies the diggings where the difficulty originated, and these are situated above the other claims, and of course were supplied first. The Chinese purchased these two claims of Lane & Sanders, miners, who used from sixty to seventy inches of water upon them, while the Chinamen used only forty inches. The miners upon the lower part of any branch always suffer more or less for want of water. The above instances, and possibly some others like them, furnish the whole ground of complaint out of which have been manufactured the extraordinary reports of partiality to Chinamen by the Ditch Company.

Sacramento Daily Union, March 10, 1858

In other words, miners on the lower end of the ditch may receive less water during periods of low flow such as during the late summer months. Because the Chinese claim was receiving all the water they wanted while some European miners had to work with less water, the hydraulic facts morphed into a water monopoly discriminating against white miners.

Catlin emphasized that the company maintained impartiality toward all of its customer. In 1863, Amos Catlin, who was a lawyer, would argue before the U.S. Supreme Court for the original Hay’s map of the Leidesdorff land grant upon which he and other’s purchased property from the Folsom estate. Early in 1864, the Supreme Court sided with Catlin’s position and the question of the boundaries of the land grant were put to rest.

It is not known if the population of Chinese increased or decreased after the Alder Creek riots. There were plenty of other mining opportunities outside of Granite Township. In Placer County, along the North Fork Ditch mining region there were 369 Chinese individuals, mostly engaged in mining activities according to the 1860 census records (see Placer County Chinese Miners.) Unfortunately, the animus toward the Chinese would grow in the years to come and acts of violence would continue to increase against this immigrant population that was little different from the European immigrants who came to California looking for a better life.