The Rosalie Remi Lamblet Murder in Folsom

“Muertre, muertre” he shouted as he stumbled down the street with blood dripping from his wounds, mixing with his sweat and dust from the road. When Francois Lamblet became excited, he always reverted to his native French language. Now he had something to be really be excited over, his wife Rosalie had been stabbed and he had also been sliced on his side. On this hot August night in the town of Folsom, 1879, Francois was running to get help for his wife while shouting “murder, murder” to awaken the sleepy little town at one o’clock in the morning.

As Francois approached the foot bridge at Riley and Figueroa streets, wearing only his night shirt, streaked with blood and sweat, his grandson, who had been staying with him and Rosalie, caught up to him. Frank Mette was 12 years old, asleep, when he heard someone jumping through the window of the room his grandparents shared. Then he heard his grandfather yelling “murder” as he ran away from the house.

As Frank crept towards his grandparent’s bedroom he could hear his grandmother call to her little poodle dog, “Here Ruby….sick ‘em.” Sheepishly, Frank asked, “What is the matter, grandma?” In a weakened voice Rosalie replied, “I am dying, jump out of the window and save yourself.” Rosalie, bleeding heavily, lost consciousness and fell against the wall by the window. Without asking any further questions, Frank ran to the little room by the kitchen where he had been sleeping and jumped out the window.

The young boy, having no sense of what was happening, could here his grandfather yelling as he headed toward town. Frank caught up to his grandfather at the foot-bridge and he proceeded to follow him onto Sutter Street. Francois’ shouts of murder attracted a small gathering of men in front of the water trough at the Central Hotel. Alexander Milroy joined Mr. Brophy and Charles Sheehan in an excited conversation with Francois Lamblet.

In the chaos and confusion of the moment, Frank did not hear or understand the conversation beyond the gentlemen asking Francois about the violent knife attack. The young boy saw Francois lift his night shirt to reveal a wound and pointing to the scratches on his leg. Frank was instructed to head down to the fruit drying warehouse where Mr. Brophy worked and wait there. Francois implored the men to accompanying him home as his wife had been murdered.

On this dark and moonless early morning in August, Milroy acquired a lantern and the men, led by Francois, started up the hill to his house. All of the doors to the little house at the corner of Scott and Mormon streets were locked. From one of the side windows the men could here a woman moaning. Francois exclaimed, “She is not dead yet, I can hear her.” Brophy helped boost Francois through the window, not knowing if the assailant was still present or not. Francois went to the front door, unlocked it, and let the men inside. They found Rosalie not murdered, but dying from the knife wounds.

Rosalie lay bleeding to death. A thick pool of blood had gathered around her body from all of the cuts she had suffered earlier. Francois requested the men present to pick her up and place her on the lounge. Shortly thereafter, Dr. Rhodes who had been sent for, arrived to dress the wounds. The loss of blood was too great. Rosalie Remi Lamblet died on August 16, 1879.

Francois and Rosalie Immigrate To Folsom California

As with most immigrants, Rosalie and Francois came to the United States in the early 1850s seeking a better life. They brought with them their first daughter Eugenia who was born in 1848 in Alsace, France. The family made there way to Wisconsin where they had a son, Camille, born in 1853, and another daughter Marie Clara, born in 1855.

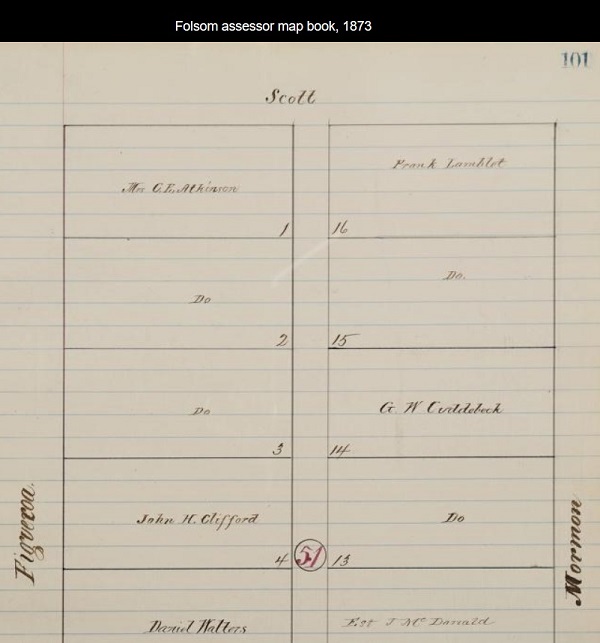

They eventually made it to California and settled in Folsom where Francois could ply his trade as a barber. On September 1, 1865, Francois Lamblet became a naturalized citizen of the United States. One of his sponsors was Peter J. Hopper, a local attorney and publisher of the Folsom Telegraph. Business was good for Francois Lamblet and he earned enough money to purchase a lot in Folsom up the hill from the business district on Sutter Street.

Lot 16, in block 51, was at the corner of Scott and Mormon Streets. The Lamblet’s kept a cow and chickens that Rosalie would sometimes sell to the local Chinese immigrants. In 1866 the Lamblet’s daughter Eugenia married Henry Mette. Mette had a vineyard and winery on the South Fork of the American River not too far from Folsom. The Mette vineyard was next to Benjamin Bugbey’s Natoma Vineyard, although not as famous.

Death visited the Lamblet family in February 1873 when Camille, their son, died at 19 years of age. Some people speculated that the death of Camille gave Francois an excuse to consume more alcohol, which there was no shortage of in Folsom. He was frequently seen around town drunk, in between haircuts, shaves, or heading home.

The impression of Francois Lamblet around Folsom was evenly mixed. Some people found Francois a nice guy and others found him rather gruff and distasteful. Of the people who found Francois less than gentlemanly, most of them were women. The conflicting opinions of Francois mirror the contradictory statements Francois gave on the night of the attack and the days afterward. It did not help that the crime scene was thoroughly trampled upon by neighbors and newspaper reporters rummaging through the house as the sun rose over Folsom to start another hot August day.

The Sacramento Daily Record Union even lamented the lack of law enforcement professionalism and knowledge when it came to investigating gruesome crimes of this nature.

Another mysterious outrage has been committed in Folsom. The murder of Mrs. Lamblet bids fair to rival the Wheatland mystery in difficulty, though as usual in such cases there are scores of busybodies ready with theories to explain everything…The real source of perplexity is such cases is the lack of intelligent police help in studying and following them up…It is clear that in small towns like Folsom,…,there can be no trained and experienced detective force. If we had a system of inquests which gave us the skill in medical jurisprudence every Coroner ought to possess, it would be much easier to unravel these mysteries.

Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 8, Number 138, 19 August 1879

The editorial was published just three days after the murder and would be very prescient. The ‘busybodies’ the newspaper referred to were the townsfolk who had already declared Francois guilty of murdering Rosalie. But other investigative biases and sloppy police work would make bringing a murderer to justice difficult.

Folsom in 1879 could be a very sleepy little town in the oppressive heat of mid-August. The mining boom had long past, the Sacramento Valley Railroad, of which Folsom was the terminus, was in decline, and they had just started building Folsom State Prison. Fortunately, the Natoma Water and Mining Company had extended their network of water canals in and around Folsom. Agriculture, vine and tree fruits, were a big part of the regional economy. Hence the fruit drying facilities that Frank Mette retreated to after following his grandfather down to Sutter Street after the attack.

The Sacramento Valley Railroad made the 22-mile trip into Sacramento pretty easy. Many people commuted from Folsom to Sacramento every day in 1879. On August 15th, Francois took the short train trip into Sacramento. One of the train employees remembered Francois displaying a dirk or dagger knife to fellow passengers. Francois also commented that his wife was not enamored with him having a weapon of this sort. She complained that he might hurt someone after he had been drinking.

When Francois returned from Sacramento, in the heat of the afternoon, he was not feeling well so he went home. He rested for a couple of hours and then told Rosalie he was returning to the barber shop. He was hoping to close up the barber shop about 7:30 when his neighbor, Mr. Sturgis, came in and asked for a haircut. After the haircut, Sturgis got the clock in the barber shop working and then waited for Francois to clean up the shop. Sturgis thought they left Sutter Street about 9 p.m. and walked up the hill to their homes where they parted ways.

The following account of Francois’ actions after he left his neighbor Sturgis comes from an interview with the Sacramento Daily Record Union reporter the day after the murder on August 17th. The account was prefaced with the information that Francois spoke barely above a whisper while lying in bed and his English was broken as French was his first language.

Francois reckoned he arrived home about 9 p.m. after he parted with his neighbor Sturgis. When he arrived home, Rosalie was peeling peaches in the kitchen. He took a cup of milk and some bread for supper, talked with Rosalie for a bit, then went to bed. Rosalie followed her husband to bed shortly thereafter. Francois noted that when Rosalie came to bed, she said it was 11 o’clock, but he remembered the clock was running fast, so it must have been 10:30 p.m. The next event Francois remembered was being struck on his side and then someone grabbing him by the throat. Rosalie called out, “Murder, murder, they kill me”.

Francois continued, “I jumped out of the window, they struck me right here on the bone, when I got struck I made a jump and I went from the corner of the bed through the window, the window was up and the blinds were closed, the blinds were kept by a little string, I had no trouble to go through, just as I got through I felt something got me by the leg, but I was heavy and I went down, I went down on my elbow, I ran down town and yelled, ‘Murder, murder, come and help us’, when I went through the window I head them striking her.”

Under questioning by Deputy Sheriff Bugbey, Francois said his wife was in bed when he fled, he ran to the back gate, opened it up and fled down the street. Francois conceded that the motive for the attack must not have been theft as $25 was still in the cigar box and both his silver and gold pocket watches were still in his bedroom.

The presence of Deputy Sheriff Benjamin Bugbey became problematic for the prosecution of the case. Bugbey was the first law enforcement officer on the scene because he only lived a couple blocks away from the Lamblets in Folsom. He had lived in Folsom since 1856, was the Constable of Granite Township from 1856 to 1860, when he was elected Sheriff of Sacramento County. Bugbey lost the nomination of Sheriff to James McClatchy in 1863. He then spent most of his energies building his winery producing wines, brandies, and sparkling wines from his Natoma Vineyard on the South Fork of the American River in El Dorado County.

Bugbey’s Natoma Vineyard and winery imploded financially in the early 1870s. The property was subsequently sold at auction, but he was able to retain ownership of his Folsom lots and residence with the help of his wife Martinette. Unfortunately, the stress of losing his small winery empire, along with impending bankruptcy drove Bugbey to heavily consume the products he used to produce. It was only a couple of years earlier that Bugbey, in a drunken stupor, tore up his Folsom house, smashing furniture, and spawning rumors that he was physically and verbally abusive to his wife Martinette in 1877.

Constable Kimbal was called to calm Bugbey down as he continued to rage in an alcohol induced frenzy of destruction at his Folsom home in 1877. The constable decided he had to arrest Bugbey for disturbing the peace. Bugbey thought otherwise, drew his own pistol and shot at the constable. Kimbal was only grazed by the bullets whizzing past his head and was able to subdue and arrest Bugbey. The reputation of Bugbey was not enhanced by the rumor that he started the Folsom fire in 1871 destroying not only his own building and the insured winery contents, but also that of the Jolly hardware store.

Two short years later after attempting to shoot a constable, Bugbey was appointed as a Deputy Sheriff by his good friend Sacramento County Sheriff Moses Drew. Because of his proximity to the Lamblet residence, Bugbey was is in charge of the murder investigation. Bugbey would exacerbate the perception of incompetence by not securing the crime scene, allowing evidence to be taken away and displayed in town, and the failure to prevent Francois from attempting suicide while under his watch.

However, Bugbey was forced to place Lamblet under arrest pending a formal inquiry. Instead of transferring him to the county jail in Sacramento, Bugbey put him under house arrest and under the supervision of guards. The Lamblet’s daughters Clara and Eugenia came to visit Francois after the horrific event. As his daughters were outside preparing to leave, Francois took a razor and cut his throat. He called out to the man who had been guarding him and said, “Mr. Slater, I have cut my throat.”

Even though there were reports of his imminent demise, Dr. Rhodes stitched up the cut and Francois survived the self-inflicted wound. Shortly after Francois’ feeble suicide attempt, Deputy Sheriff Tim Lee arrived at the house. Sheriff Lee beseeched Francois to tell the truth about the night of the attack as his wound might prove fatal. Francois replied, “Oh, Mr. Lee, I never struck my wife. I never did that thing to my poor wife. I never struck her. I had a good wife. I am guilty of cutting my neck, but I did not hurt my wife. I don’t want to go to Sacramento.”

It would take several weeks for Francois to recover from his wounds and settle his composure. In mid-September, and examination of the facts was initiated before Justice Sheldon of Granite Township in Folsom. Former District Attorney George Blanchard was appointed to represent Sacramento County and Francois retained Henry Edgerton for his defense. The examination was held behind closed doors and lasted for an unprecedented three weeks. One revelation that did leak out was that Deputy Sheriff Bugbey was under suspicion of being an accessory through his actions to shield Francois Lamblet from being indicted for murder.

The speculation and rumor was so intense that Bugbey must be involved in some sort of cover up on behalf of Francois that District Attorney Blanchard was forced to release a statement to the newspapers. He first refuted the rumors that Bugbey had insulted a witness and an inaccurate report that the District Attorney had requested that Bugbey be relieved of his duties surrounding the Lamblet case. Both, Blanchard contended, were not true. Then he addressed the public sentiment regarding Bugbey in Folsom.

Sometime before the case came on I learned from the residents of Folsom that there existed there an intense feeling of distrust against the officer who then had the custody of Lamblett, and not knowing what cause there was for such feeling, I had a talk with Mr. Drew, and Under-Sheriff Estill about the matter. Mr. Drew, as Sheriff, was responsible for the safe-keeping of his prisoner, he had confidence in his Deputy, and with the course he took in the matter I have no fault to find. Geo. A. Blanchard District Attorney.

Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 8, Number 173, 29 September 1879

It is doubtful that Blanchard’s refutation of rumors or explanation of the actions of Sheriff Drew and Deputy Sheriff Bugbey satisfied those who were discontent over the whole affair. A gruesome murder had been committed in their little town and four weeks after the prime suspect had been identified, there had been no justice. The wheels of the justice system were moving slowly.

District Attorney Blanchard brought the case before the Sacramento County Grand Jury on October 6, 1879. A large number of witnesses were subpoenaed to testify before the Grand Jury in the accusation of murder against Francois Lamblet. Three weeks later on October 28th, the Grand Jury found a true bill presented by the District Attorney for an indictment of murder against Francois. Now, Francois Lamblet’s fate would be in the hands of a jury of his peers.

Francois Lamblet Murder Trial

Francois assembled an impressive team of attorneys for his defense at the murder trial scheduled for early March 1880. First, there was Henry Edgerton a former District Attorney from Napa County who also served in the California Legislature. He was a noted orator and a prominent Republican. Next, William Crossett was also a Republican and ran for Assembly on the same ticket as Peter Hopper for Assembly and Moses Drew for Sacramento County Sheriff in 1875. Crossett owned numerous lots in Folsom very near the Lamblet residence.

The final attorney was Amos Catlin who originally organized the Natoma Water and Mining Company in the 1850s. Catlin went on to argue on behalf of the Folsom estate for a map of the Leidesdorff land grant before the United States Supreme Court. While Catlin was somewhat of a reluctant Republican at times, his knowledge of the law propelled him to be nominated as a justice on California Supreme Court, of which he was not successful in obtaining. Before moving permanently to Sacramento, Catlin lived in Folsom for many years in the 1860s.

The trial commenced on March 6th, 1880, and drew intense interest on the part of the residents of Folsom and Sacramento. Testimony at the trial would provide additional details that had not made their way into public knowledge during the previous five months since the murder.

On the night of the attack, both Rosalie and Francois were assaulted with a blunt instrument and also a knife. The spoke of a wagon wheel was located inside the couple’s bedroom. Dr. Rhodes testified that the knife wounds to Rosalie’s arms and Francois’ right chest area were mostly likely from a double-edge knife or dagger. The dagger Francois had been seen with earlier in the day was found in his pants pocket.

The dagger showed evidence of having been recently sharpened and Ellen Gable testified that she saw Francois sharpening a knife in his barber shop the night of the murder. A day after the murder, two of the jurymen for the coroner’s inquest, Felton and Tom Long, visited Francois and asked to see the dagger it was reported he had. He denied he had one. When they insisted he did have a dagger, Francois confessed it was in his pants pocket. A search of the Lamblet property yielded some bloody clothing in the woodshed consisting of a lady’s chemise and undergarments.

Amos Catlin cross examined William Fulcher who found the clothing and learned that the items were taken into town and shown at Josh Smith’s store. Tom Long also showed the bloody clothes to people around town. The dagger was given to Constable Kimble.

Among the many visitors to the Lamblet home after the murder was Mrs. Currier. She watched over Francois as he furtively tried to sleep. In what seemed like a state of delirium, Francois awoke and said “Oh, my God, I did do it!” He asked Mrs. Currier to come near him so he could tell her the whole truth. She stated that Francois told her that on the night of the attack he was awaken by someone trying to cut his throat and his wife seemed to be suffocating. He saw no one in the room, but nonetheless, made a hasty exit through the window.

Francois asked if Rosalie had many knife wounds on her. Mrs. Currier replied that she had and it must have been the work of two assailants. Francois disagreed with her. The wounds were inflicted by the hand of one person he told her. Francois then asked Mrs. Currier why people around town thought he killed his wife. She avoided answering the question. Francois then complained about the cost of the coffin Rosalie was to be buried in. He thought a less expensive coffin would have worked just as well.

Then Francois made a comment that would cast a tint over the whole investigation. He told Mrs. Currier that Mr. Bugbey was his friend and would do almost anything on his behalf to help him. Bugbey, he perceived, was smarter than the lawyers and he knew a dammed sight more than most of them.

Eva Jolly visited the Lamblet home shortly after the murders and saw blood in the bed room and bloody hand prints near the kitchen and on chairs. She testified that Francois said he knew nothing about the murder and saw no one. Deputy Bugbey then arrived at about 2 o’clock in the morning.

At the request of Francois, Bugbey cleared the room so the two of them could have a private meeting. Francois confided that he had an unpleasant business transaction over a piece of property. He was going to have to foreclose on the property he had sold to a local gentleman. He felt the impending foreclosure may have induced the man to attack him and his wife. Lamblet was awarded a judgement against a T.J. Patten in early May. However, the man in question was found and proved to have an alibi for the night of the murder.

The potential bias of Bugbey for Francois surfaced when Mr. Crable was called to testify. He recalled talking to Bugbey the day after the murder at the Lamblet’s house. Allegedly, Bugbey told Crable that Francois was a friend and he was going to stand by him, even though he had a warrant for his arrest in his pocket. Crable also mentioned that he had words with Bugbey indicating a disagreement on how Bugbey was conducting the investigation.

Bugbey refuted Crable’s testimony saying he never showed the man the warrant. Additionally, Bugbey did not recall ever telling Crable that he thought Francois was innocent and he would stand by him because he was a friend. He further testified that he had worked to find the murderer in an impartial manner and always kept guards at the Lamblet house.

A recurring line of questioning centered on the marital harmony between Rosalie and Francois. Eva Jolly knew of no quarrels between them. Lizzie James testified she never saw Rosalie or Francois have a serious argument, “They sometimes passed words at each other, generally using French words so that I could not understand.” Ann Custer, a next door neighbor, said she often saw Francois drunk and promised to help Rosalie if she ever asked. She often heard them quarreling.

Esther Hysman lived at the Lamblet’s for two years, but left boarding there about 6 months before the murder. She said Rosalie and Francois used to quarrel when Francois was drunk. She witnessed Francois strike Rosalie with chairs twice and call her names. He was jealous of her and thought she may have been encouraging inappropriate attention from other men. Eugenia Mette, Rosalie and Francois daughter, testified she never saw her father strike her mother or threaten her. Of course, she had not lived at home since marrying Henry Mette back in 1866. Clara Euer, the Lamblet’s youngest daughter echoed her sister’s description of the Lamblets as never quarreling and she never knew her father to carry a weapon.

Testimony at the trial illuminated the numerous inconsistencies and contradictions in Francois’ description of the night of the attack. He alternately told people he felt someone grab his neck and told others he was not grasped. Even though Francois said the attack occurred primarily in the bedroom, most of Rosalie’s blood was found in the front room. Bugbey even noticed how the walls and doors leading to the dining room looked as if the blood had been squirted from a syringe.

Two points of concern centered around how the assailant may have entered the home and why the Lamblet’s dog never barked at an intruder entering the property. The Lamblet house had a back door made out of wood lattice in order to let any stray breeze enter the house during the summer months. There was hole at the bottom of the door where the lattice had been broken apart approximately 16 inches in diameter. Lizzie James said the hole was made by Rosalie’s poodle dog jumping through it to get some meat. The hole was examined by several men who climbed through it to prove the assailant could have gained access to the house via the hole.

There were also numerous questions posed about the dog Francois kept. Some people characterized it as vicious, savage and always barking. Other witnesses testified they were never bother by the dog and did not consider him threatening. Regardless, none of the neighbors heard the dog bark either before or during the murder. George Custer, Francois’ neighbor, said he heard the iron hook of the Lamblet gate fall closed. He then saw Francois running from the gate and yelling murder or muertre.

Custer had a light burning bright in his house, as were a couple of other homes in the neighborhood indicating that Francois did not need to run all the way into town, but could have inquired for help at a neighbor’s house. Custer and his wife went out into their backyard to attempt to ascertain what the commotion was about. They were greeted by the Lamblet’s dogs barking at them. Up until that time they had not heard the dogs that evening. After a short period, Francois returned with a group of men following him with lanterns.

The testimony of Mrs. L. How, who was an editor at the Folsom Telegraph, was most intriguing. She said she visited Francois on Saturday following the murder. She said Francois recounted that while both he and Rosalie were sleeping, Rosalie jumped up and starting shouting murder three times. Francois thought he was struck by something. He ran into the dining room and Rosalie followed him screaming murder, murder, murder. Her arms were raised up and flailing. At that point Francois jumped out the window. When he was outside, he heard her groans growing weaker and weaker, and he knew she was dying.

From all of the evidence presented and all the testimony recounted, Francois’ description to Mrs. How of the attack is the most cogent and plausible. I have to agree with Mrs. How with her statement at the trial, “…my belief [is] that defendant murdered the deceased.”

Absent a mystery attacker, it was Rosalie who struck Francois. Whatever argument they were having escalated. The physical altercation moved from the bedroom into the front room where Rosalie, attempting to defend herself with her arms lifted up, was stabbed and cut by Francois. This splattered blood on the walls. Francois then leapt from the window, perhaps in horror of what he had done, and listened for life. Francois admits that he did not hear further attacks on Rosalie, contrary to other statements he made.

The man who cut his neck with a razor to feign a suicide attempt, was surely capable of cutting himself with a knife on his chest to simulate an assault from an intruder. After slicing his flesh, and knowing there was no intruder, he had to buy some time. Instead of running to the nearest home with a light for help, he travelled several blocks down into town yelling muertre or murder. Upon arriving back at the Lamblet house with the party of men, Francois was surprised Rosalie was still alive as he could hear her groaning through the open window.

What man leaves a house where his wife is being brutally assaulted? Why didn’t Francois stay and defend Rosalie? Because he was the assailant. What man yells murder instead of help? Because, at that point, he didn’t want help. He needed a reasonable period of time to elapse for the mystery attacker to have run away and for Rosalie to die. What man would leave his grandson alone in the house with a murderous attacker? Francois knew that the boy was safe because he, as the knife wielding assassin, had fled the scene.

On March 12th, Catlin and Edgerton, attorney’s for Francois, concluded their review of the evidence and closing arguments. George Blanchard then followed with his closing arguments for the people. Judge Clark then gave instructions to the jury and they retired into deliberations in the afternoon. The jury returned three hours later with a verdict of “not guilty.”

Francois Lamblet removed himself from Folsom and settled in Grass Valley where he opened another barber shop. He worked and resided there for another 10 years, dying on July 12, 1889. Sophary Euer, his son-in-law, was the executor of his estate. To Eugenia Mette, his oldest daughter, Francois left $1. To Clara Euer, his youngest daughter who was residing in Clarksville, El Dorado County at the time of his death, Francois left all of his property in Grass Valley including the barber shop furniture and fixtures.

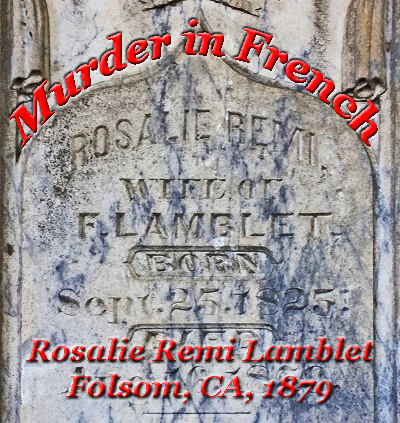

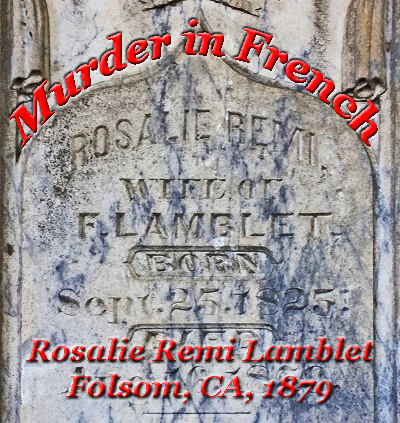

Rosalie Remi Lamblet is buried next to her son, Camille, in the Folsom Cemetery.

Notes and Sources

- Most of the newspaper accounts spell the last name with two t’s: Lamblett. I have chosen to use the spelling of one ‘t’ listed on official documents.

- On April 19, 1877, the Sacramento Valley Railroad was consolidated with the Folsom and Placerville Railroad to form the Sacramento and Placerville Railroad.

- Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 29, Number 4508, 2 September 1865

- Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 8, Number 57, 9 May 1879

- Daily morning times, Volume I, Number 30, 17 August 1879

- Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 8, Number 137, 18 August 1879

- Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 8, Number 138, 19 August 1879

- Los Angeles Herald, Volume 12, Number 66, 21 August 1879

- Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 8, Number 141, 22 August 1879

- Placer Herald, Volume 28, Number 3, 23 August 1879

- Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 8, Number 164, 18 September 1879

- San Jose herald, Volume XXVII, Number 68, 18 September 1879

- Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 8, Number 166, 20 September 1879

- Daily Alta California, Volume 31, Number 10760, 29 September 1879

- Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 8, Number 173, 29 September 1879

- Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 8, Number 177, 3 October 1879

- Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 8, Number 180, 7 October 1879

- Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 8, Number 183, 10 October 1879

- Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 8, Number 199, 29 October 1879

- Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 11, Number 11, 5 March 1880

- Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 11, Number 12, 6 March 1880

- Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 11, Number 14, 9 March 1880

- Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 11, Number 15, 10 March 1880

- Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 11, Number 16, 11 March 1880

- Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 11, Number 17, 12 March 1880

- Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 11, Number 18, 13 March 1880

- Morning Union, Volume 42, Number 5755, 15 June 1889

- Morning Union, Volume 43, Number 5779, 13 July 1889

- Morning Union, Volume 44, Number 6013, 16 April 1890

- Great Registry, Voter Registration

- Census Date 1870, 1880

- Nevada County Probate Documents

- U.S. Find A Grave Index

- Benjamin Norton Bugbey, Sacramento’s Champagne King, Kevin Knauss, 2019.