An ancient river bed several hundred feet thick of eroded rock and gold once flowed toward the Pacific Ocean. Then massive lava flows covered the river. Millions of years later the remnants of the river bed with the placer gold top with lava was named Table Mountain north of Oroville, California.

Gold found, Cherokee gets named

A group of Native Americans from Georgia settled in the area working the exposed auriferous gravel deposit north of Table Mountain and called the area Cherokee. By 1855 there were several small placer mining operations working the ground. The process of extracting the placer gold from the gravel was hard work because there was no stream of river to provide the water necessary to wash the gravel from the gold. Consequently, most of the gold mining occurred during the winter months when it rained.

Rich placer gravel with no water

The placer gold deposits around Sugar Loaf Mountain and the north end of Table Mountain would yield $20 to $50 per day per man.

One of the monitors used in hydraulic mining in Cherokee Flats.

This was a good enough return on the labor to get men coming back to mine. Over time several mining operations emerged including the Cherokee, Spring Valley, Eureka, and Cherokee Flat Blue Gravel companies.

Dams, canals and siphons

The Spring Valley Company was the first mining operations to bring water to the Cherokee Flat mining area. This was a difficult task because the areas elevation and it was separated from major Sierra creeks and rivers by the deep ravine of the North Fork of the Feather River. In 1870 they began by building a dam in the Concow valley nine miles north of Cherokee Flats. Next, they ran a water ditch to the west branch of the North Fork of the Feather.

Largest inverted siphon ever built

To bridge the Feather River 1/2 mile wide ravine, the newly named Spring Valley Water Works Company brought in engineer Herman Schussler who had previously been working on the water works for the city of San Francisco. Schussler designed an inverted siphon to transport the water from the east side to the west side of the ravine.

Riveted steel plates to create a siphon tube

The inlet of the pipe was 150 feet above the outlet, with a vertical height from the lowest point to the grade line of 900 feet. The

Rivets on approximately 30″ penstock pipe line from Kunkle reservoir leading to the power house. Is this pipe original 1870’s. Even sitting in the blazing sun, it was cool to the touch with the water flowing through it.

pipe was 30 inches in inside diameter and was designed to carry 1,900 miner’s inches of water. Its thickness ranched from one-quarter of an inch to three-eights of an inch. At the lowest point it achieved a pressure of 887 fee of head or 380 psi- the greatest pressure that water had ever been carried anywhere in the world.

The pipe was supported over the ravine by means of a trestle at a height of 70 feet. All of the rest of its length was buried in a trench and covered with earth at a depth of five feet to prevent undue expansion and contraction. – Hydraulic Mining in California, A Tarnished Legacy by Powell Greenland, 2001.

On site construction

The siphon pipe from end to end was close to 14,000 feet in length. Much of the pipe was manufactured by Risdon Iron Works in San Francisco. An additional 87,000 feet of pipe was manufactured on site with steel plates supply by Risdon. The sheets of iron, shaped with the necessary arc to complete a 30 inch diameter circle, were riveted together.

Enormous amounts of money and labor to deliver water

The fabricated iron pipe along with other water canals and flumes delivered the water to Cherokee Flats. In 1871, Cherokee Hydraulic Mine began their own water conveyance systems with a dam on Butte Creek. They also had an inverted siphon with a vertical drop of 680 feet and pressure of 295 psi.

Rivals merge over water

In 1873 the Cherokee Company and Spring Valley Mine merged and retained the name of Spring Valley Mining and Canal Company. Part of the drive to merge was the constant need for ever greater volumes of water. Shortly after merging the new company completed water ditch created by a small dam on the west branch of the North Fork Feather River.

In 1873 the Cherokee Company and Spring Valley Mine merged and retained the name of Spring Valley Mining and Canal Company. Part of the drive to merge was the constant need for ever greater volumes of water. Shortly after merging the new company completed water ditch created by a small dam on the west branch of the North Fork Feather River.

A small river of water hitting Table Mountain

With the additional water and acquiring the Welsh Company Mine working the north face of Sugar Loaf Mountain, there were nine hydraulic monitors operating with nozzles sizes of from 5 to 7 inches in diameter. They were operating under 250′ of pressure head, 105 psi, and the seven inch giants were pouring 1,000 miner’s inches of water against the hill side.

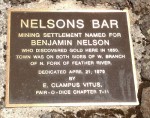

Locating the water works of history

The details are sketchy as to when the Kunkle reservoir was built. If my research is correct, that the Schussler siphon cross the Feather between Nelson Bar Road and Concow creek, it would most likely indicate that the Spring Valley Company built it. The water ditch runs from where the Schussler siphon would have reached the west side of the ravine into the Kunkle reservoir.

Was power generation part of the original plan?

While most of the ditch is open, the water is taken through tunnels, pipes and flumes to minimize its length and in turn the initial cost of

Hand place stones making up the foundation of the dam at Kunkle reservoir.

construction. One piped section starts at the base of Kunkle reservoir and terminates at the PG&E Lime Saddle Power Plant. The water has a 415 foot fall from the base of the dam into the turbines at the power plant. It has been recorded that the Spring Valley Mine operated 24 hours a day with the aid of arc lamps. I am not sure if this power plant was part of the electrical system for the mine or if it was added later.

Current pipe indicates hand made steel penstock

The steel riveted pipe conveying the water from Kunkle reservoir is similar to what is described as the type of pipe manufactured for the siphon and other parts of the Spring Valley Water project. It is evident that a rock crib was constructed to cradle the steel riveted pipe as it exits the dam and heads south to the power house. Is this the original pipe from the 1870’s? Are the hand placed stones that make up the foundation of Kunkle reservoir original construction?

Mining debris removal adds expense

View of Cherokee hydraulic mining district from Google Earth Street view. Looks very similar to Malakoff Diggins.

All the water and tailings washed from Sugar Loaf Mountain and the north end of Table Mountain had to go some place. The highest yielding gravel was below the flats that the hydraulic mining companies were working. As they created a bath tub they created an additional drainage tunnel 3000 feet long to deliver the water and tailing into Sawmill ravine (on the north side of what is todays Highway 70). This dumped all the debris into Dry Creek.

Debris dams stop hydraulic mining

Lawsuits over the hydraulic mining waste destroying down stream farms and orchards led the Spring Valley Company to purchase all the property and create a huge debris field of mine tailings or “slickens” as they were often called. But the lawsuits against the hydraulic mines of the Cherokee Flat area and other operations didn’t stop. In 1884 the Sawyer Decision virtually shut down hydraulic mining in California. In order to operate with out injuring the property rights of downstream land owners the hydraulic mines of Cherokee Flat and Malakoff Diggins had to install debris dam to capture their tailings from entering creeks and rivers.

That’s a lot of gold

The added expenses along with dwindling gold being extracted from the mercury laden sluices forced most hydraulic mines in the

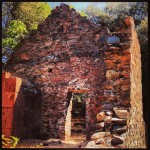

Many early Cherokee buildings were built with stone walls and foundation.

Cherokee area to shut down by the late 1880’s. Different production methods were tried over the years that avoided discharging waste water. When all mining operations ceased at the turn of the 20th century it was estimated that the Cherokee Flat mines produced $13,000,000 in 1911 figures. That makes it one of the most productive hydraulic mines in California.

Thanks to Powell Greenland

Most of reference material was gleaned from Hydraulic Mining in California, A Tarnished Legacy by Powell Greenland, The Arthur H. Clark Company, Spokane, Washington, 2001. Other references were found on line and noted with hyperlinks when available. I have tried to be as diligent as possible and not create any history or report something in error. If I have misrepresented a location or historical fact please let me know so I can make the necessary corrections.

Most hydraulic history inaccessible

The closest I was able to get to Cherokee and Spring Valley hydraulic mining sites.

Unlike Malakoff Diggins State Park, the different parts that make up the Cherokee Flats mining district from the actual mining site, tunnels, water canals and siphon locations are on private property. If you have access to any of the property that is historically significant and would like it documented, please contact me. Hydraulic mining and its legacy is an important part of California history and should be properly documented for future generations.

Photos and video of Table Mountain Cherokee trip

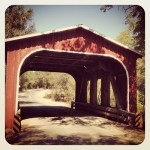

Below is a photo gallery of the places I was able to visit while on a trip to learn about Cherokee Flats mining district. Cherokee Road takes you from the north end of Oroville up and over Table Mountain and down into the ghost town of Cherokee. It is a beautiful drive. I did detour to the covered bridge in Oregon City just off of Cherokee on Derrick Road. The other photos were taken along the Miocene Ditch water canal, Lake Oroville and Kunkle reservoir. See also Table Mountain Hike post

Click on thumbnail to enlarge picture or map.

Historical hydraulic mining photos acquired in 2014