Most of the men elected to the 1854 California Senate were not from California. At best, they were only residents in the last five years having migrated to California in 1849 during the Gold Rush. While some men had put down roots in one location early on, the new residents in California were mobile, moving between different mining claims, from tent to cabin to wood frame house, and were constantly displaced by floods and fire.

Consequently, having a state capitol that had moved from Vallejo, to San Jose, then to Benicia, was inconvenient, but also in accordance with the experience of most California newcomers. The state was just a toddler compared to its established counterparts on the Eastern Seaboard with rich colonial histories. California was a petri dish of different organisms growing on the substrate of mining, agriculture, and transportation. Small communities were forming all over the state and only time would determine if they would be viable.

Sacramento was one of those communities that exploded. It was the gateway to the mining districts along the forks of the American River. The Sacramento River offered the watercourse to deliver men and supplies from San Francisco. Sutter’s Fort was seen as a modest symbol, that in addition to providing some shelter, demonstrated that the interior of California was suitable for habitation.

Land speculators quickly secured title to the land from John Sutter’s son and began mapping and selling lots. Sacramento had its problems. There were questions over Sutter’s land title that led to a settler’s riot. There was a cholera outbreak and the flood of 1850 that surprised many of the new inhabitants. But Sacramento had many advantages such as two rivers, flat topography, arable soil for agriculture, and wide-open expanses for ranching.

Communities live and die by their associated business interests. There must be wealth generators in order for the community to create a sustainable circulation of goods, services, and a money. Sacramento had the base business to sustain itself. Not only was Sacramento importing mining supplies, building materials, and people, it was also exporting gold and a growing list of agricultural products. This meant that Sacramento was less dependent on one industry and slightly more insulated from macro-economic downturns.

The Whig Who Put Sacramento On The Map

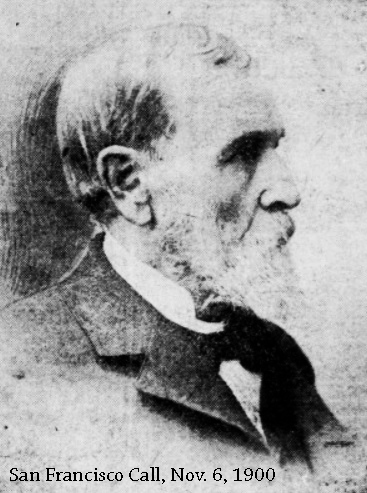

One of the men who saw Sacramento from the beginning was Amos P. Catlin. He passed through Sacramento on his way to the mines at Mormon Island on the South Fork of the American River. Catlin was born in Red Hook, New York in 1823 and was a practicing lawyer in New York City when he decided to travel to California in 1849 to mine for gold. By 1850 he was active in the local Bar association, mining organizations, and the Whig political party. Catlin’s home base at this time was one of those new mining communities, Mormon Island.

Catlin’s first attempt for elected office was as a Whig for an Assembly seat in 1851, but he was not successful. He would continue to pursue his mining interests and his stature as a reasoned individual with respect to the development of the mines would increase. Foreshadowing his employment at the Sacramento Daily Union as an editor in the 1860s, Catlin’s reports on the mining industry were published in the newspaper. In November of 1851 he provided an optimistic view of future mining in the region, “The upturned bars, the piles of poor earth will be sluice-washed by the torrent, the gold lodged in crevices and pockets, and the sand again formed into bars and banks. Let industry increase, economy be practiced, skill be applied, and desires moderated and the results will be the same.”

Catlin was referencing the winter and spring freshets, the raging torrents of the American River from heavy winter rains or spring snowmelt, that would deposit more placer gold in the sand bars as a means of replenishing the gold dust. This was not to be the case. Even though these freshets did replenish some placer gold, it was never at the levels originally mined in river beds. The volume of placer gold needed to sustain mining along the forks of the American River were contain in the banks and benches next to the river. These dry diggings, next to the river, needed water from above the mining claim to be efficiently worked.

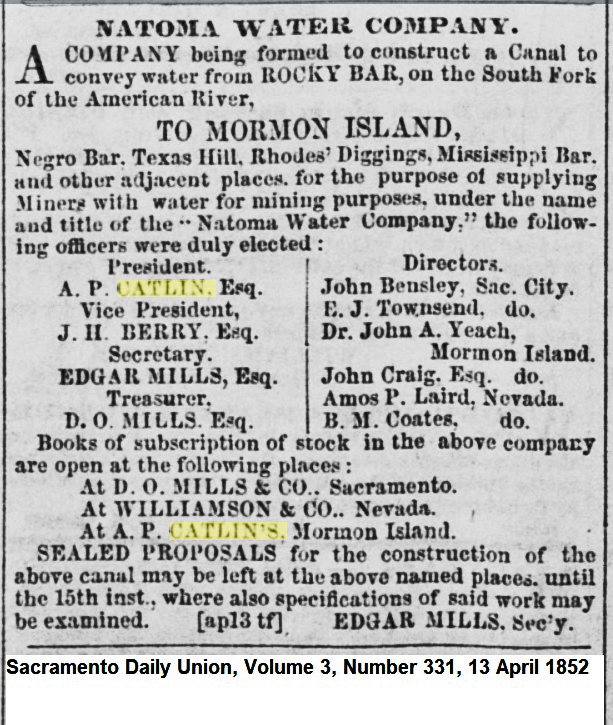

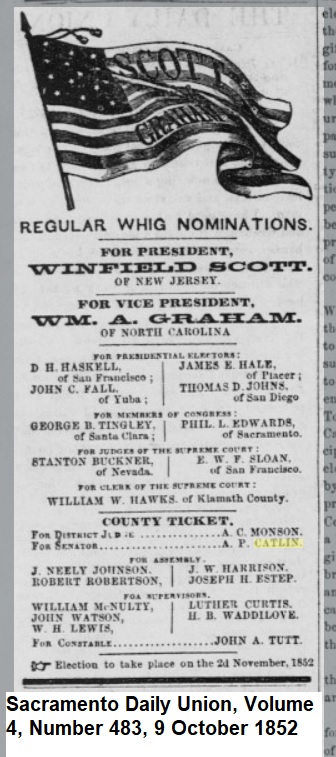

In April of 1852 Catlin organized the Natoma Water Company to build a water ditch from east of Salmon Falls, on the South Fork of the American River, down to Mormon Island, Negro Bar, and Texas Hill. Darius Ogden Mills was the treasurer of the newly formed company. Catlin continued his involvement in politics being nominated by the Whig Party as a Senate candidate. His candidacy was successful and he was elected a State Senator for the third session from the 9th district to commence in 1853.

The Whig political party was already in its waning days by 1853. California was a completely different political landscape from the East Coast or southern states. Catlin admired Henry Clay, one of the founders of the Whig party and aligned himself with federalist positions. While the California Whigs did not ignore national and international issues of the day, California politics were about how the state’s infrastructure and government institutions would develop to best serve the growing population and developing industries.

The Senate of 1853 was comprised of 27 Senators, 20 of whom were Democrats. Catlin was in the minority. The legislature was meeting in Vallejo and Catlin was assigned to the Commerce and Navigation Committee. Before the session was over, the legislature moved their meeting space over to Benicia.

California came into existence without a defined structure of land title. Many of the miners, and even settler’s in Sacramento, were improving land without any clear title or rules. Was the land in a Spanish Land Grant, local land speculator control, or was it part of state or federal public lands? Without maps that had been properly surveyed or a clear system to adjudicate the rights of those settlers, there was much consternation over land ownership. Catlin introduced petitions containing the names of 500 citizens from Sacramento requesting a law releasing the interest of the State to land within the city limits.

The fear of some Sacramento property owners was a protracted legal battle between the Sutter land grant, of Spanish origin, federal public land, and State interest. If any interest California might try to assert was removed from the land, future adjudication of the titles would be made easier. Catlin understood that a muddled title was a certain road block to future development. His interest in the progression of Spanish Land Grant titles would serve him well as he would go on to argue on behalf of the executors of the Folsom Estate’s ownership of the Leidesdorff land grant map before the U. S. Supreme Court in 1864.

Even though Catlin did not live in Sacramento, he worked to position Sacramento as a modern city that could attract capital, business, and possibly a government workforce. To that end, he introduced legislation to allow Sacramento to sell bonds to build a State Hospital and a bill that would entitle Sacramento County to three Senators and six Assembly members. His final push to put Sacramento on the map was legislation to move the State’s capital to Sacramento. Near the close of the 1853 session, the Senate voted against Catlin’s bill and Benicia retained the capital.

With the legislative session concluded, Catlin went back to the Natoma Water and Mining Company full time. He attended a convention of water companies, a growing industry in the foothills, focused on some of the emerging challenges faced by corporations damming rivers and cutting canals into land they did not technically own. Catlin was appointed to a committee to draft resolutions to be sent to Congress requesting certain privileges for the water canal’s constructed infrastructure. The recognition of land ownership on federal lands where the water ditches were built across would not come until 1866.

Catlin was involved with bringing water down from the mountains for mining and agriculture. Other efforts to ease the burden of traveling to the foothills and mines had been underway with the organization of the Sacramento Valley Railroad. The American River was only navigable for several miles upstream of Sacramento. It was a 23 mile trek to Negro Bar and another three miles to Mormon Island from Sacramento by foot, horseback or wagon. The region needed what the East Coast already had for moving people and freight: a railroad.

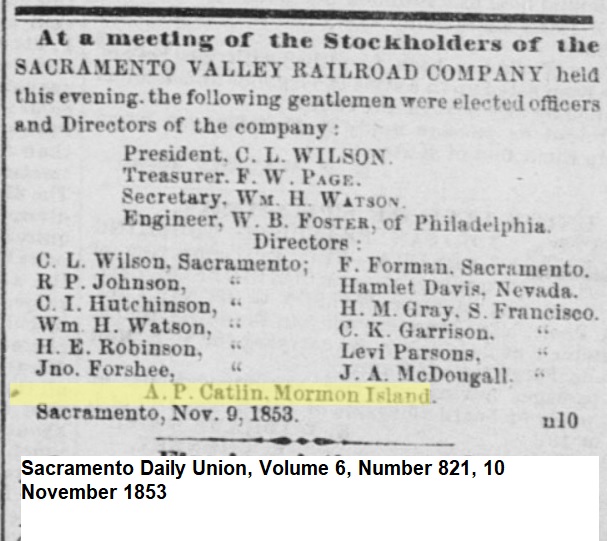

The Sacramento Valley Railroad (SVRR) was having financial challenges. Upon the third organization of the company, Catlin bought twenty shares of stock. With this 1853 iteration of the railroad, C. L. Wilson was the President and Catlin was named as a director on the company’s board. It must have been encouraging for the SVRR to have Catlin, a practicing attorney and State Senator, listed in the organization. Unfortunately, the Sacramento Valley Railroad would still have to be reorganized in the future before it was partially completed.

Senator Catlin Introduces Bill To Move California Capital To Sacramento

The fifth session of the California Senate opened in Benicia in January 1854. Catlin’s first order of business was to have the Senate request that the Secretary of State furnish them information about the publication and distribution of a map of the State. He was assigned to the Claims, Commerce and Navigation, and Judiciary Committees. On January 13, 1854, the Sacramento Daily Union published a brief mention of the Senate proceedings, “Nothing of particular interest transpired in either branch of the Legislature, yesterday. Mr. Catlin, in the Senate, gave notice of intention at an early day to introduce a bill for the permanent location of the seat of Government.”

Many in the legislature did not regard Catlin’s bill to permanently move the State capital to Sacramento with any seriousness. While Benicia did not have the economic engine that Sacramento was developing, it was quiet and easy to get to as it was situated on the Carquinez Strait where steamers from San Francisco up to Sacramento passed on a daily basis. A bigger issue pressing on the legislature was the State’s debt. California was spending more than it was collecting in tax revenue. The prospect of spending more money to move the capital again did not make financial sense.

One estimate to move the capital from Benicia was $46,000. Catlin was very much a fiscal conservative and did not like deficit spending. It’s probable that Catlin would have objected to moving the capital, if the bill was introduced by any other Senator, solely on its cost. There must have been some legislators who saw Catlin’s removal bill as a means of feathering his own nest from the stand point of his investments in the Sacramento Valley Railroad and the Natoma Water and Mining Company.

Sacramento City Pledges To Cover Cost Of Removal

To ease the cost objections, and underscore the seriousness of which Sacramento residents wanted the capital, the City of Sacramento pledged to indemnify the State upwards of $30,000 to move the capital from Benicia to Sacramento. Sacramento Mayor Hardenbergh pledged the funds on bond offered by Ferris and Smith to cover the costs of moving the archives, furniture, and other State officers to Sacramento. After a flurry of activity, Catlin’s bill was defeated in mid-January of 1854. It seems the senatorial contingent from San Francisco combined with Nevada County did not find the bill agreeable and led the question to defeat by a vote of 14 to 19.

In 1854 it was estimated that the population of California was 264,000. The majority of the population, 154,000, resided either in Sacramento County or counties to the north of Sacramento. There were 14 stage lines operating out of Sacramento on a daily basis. Two to Four steam boats traveled from San Francisco to Sacramento every day and made runs as far north as Marysville.

California Residents Want A Sacramento Capital

Up to this point, it seems as if the legislators were representing their political interests and not necessarily their constituency. The news of the defeat of Catlin’s bill finally reached distant communities and those residents had a different opinion from their elected representatives. For many immigrants, Sacramento, and Sutter’s Fort in particular, held a special place in their hearts. It was where most men began their grand adventure in California. In addition, Sacramento being the State’s capital only made sense in terms of transportation and communication of the day.

In late January the Grass Valley Telegraph published an open letter signed by many prominent citizens advocating for the removal of the capital from Benicia to Sacramento. The letter argued that, “…Sacramento in every light in which she may be considered is the great interior central city of the State, commanding all the advantages of a frequent, rapid and varied communication with every part of California, thus affording with readiness all the means and facilities of general intelligence and knowledge, which are eminently necessary to the enactment of wise and useful laws. The easy accessibility of the Capital of a State to the constituency of the Legislature is a matter of important moment among the interests of a Commonwealth.”

In early February, Senator Sawyer presented petitions from the residents of Mokelumne Hill and Jackson favoring Sacramento as the capital. A joint resolution was introduced in the Assembly to remove the State’s capital from Benicia to Sacramento. At the end of January, Assemblyman Pratt presented a petition from the citizens of Ione Valley requesting the removal of the capitol to Sacramento. The citizen correspondence helped keep the joint resolution alive in the Assembly.

The citizens of Sutter Creek made perhaps one of the more elegant appeals for Sacramento to their elected representatives in their resolution.

“Whereas, in the opinion of this meeting, Sacramento city is more acceptable to a majority of the citizens of California than any other point proposed for the permanent capital of the State; and whereas, her citizens have evinced a spirit of energy, perseverance and liberality unsurpassed in the history of this, or perhaps any other state; and whereas, in the opinion of this meeting, it would be greatly to the interest of this county, as well as of the State at large, to locate the State capital permanently in that city ; therefore, Resolved, That we respectfully request the Calaveras delegation now in the Legislature of this State, to use their utmost exertions to locate the capital permanently at Sacramento city.”

The opinion of the electorate was becoming increasingly clear and the matter for removal was referred to the Committee on Public Buildings in the Assembly. The limitations of the resources in Benicia were also becoming an issue. Committees could not meet because there were not enough rooms in the buildings in Benicia where the legislature and executive officers were trying to conduct business. The lack of meeting space was causing delays for getting bills examined and pushed through the process.

Any Place But Benicia

The regional newspapers started to sniff that the politics were changing and that there was a desire to vacate Benicia. The Stockton newspapers were advocating that the capital be located in Stockton. Senator Crabb presented a proposal offering the Stockton Court House, plus, the city would pay for the move. Crabb argued that the climate was the same as Sacramento, had river access, and as a bonus, also hosted the State’s Insane Asylum, where legislators could take a brief respite from their hallucinations of grandeur.

The Mariposa Chronicle pitched their location in the foothills as a grand place for California’s capital. The Daily Alta newspapers detailed the advantages of San Francisco as the capital. The Assembly passed the joint resolution for the removal of the capital to Sacramento and sent it over to the Senate. The smaller Senate body could not see its way forward to accept the Assembly resolution and it was voted down.

In early February, Catlin gave notice he would introduce another bill to move the capital to Sacramento. Much of the blame for the defeat of the Assembly resolution in the Senate was attributed to the Democratic caucus. Serious consideration of any move was derailed by political scandal. Senator Peck from Butte County alleged that a J. C. Palmer attempted to bribe him in voting for David Broderick for U. S. Senator. The investigation consumed the Senate’s time. Eventually, the Senate concluded the allegations were without merit.

As all bribery investigation was taking place, along with other committee meetings, another reality emerged, the legislators were bored in Benicia. It was becoming difficult to get a quorum in either the Assembly or the Senate. Many legislators were asking for a leave of absence, from Saturday through Monday, to go home to their family or just get out of town. The short boat trip to San Francisco from Benicia meant that some elected officials were in no shape to work after a little relaxation in the city.

The San Francisco Chronicle called for any location to be the capital except Benicia. Other newspapers were more targeted in their editorials for a new capital. San Francisco was more interesting, but offered too many diversions. There was a fear of the legislators debasing themselves in debauchery and whimsy in a metropolis like San Francisco. What was needed was a quiet, staid, repressed location where elected officials could focus on business and not get into trouble: Sacramento.

Catlin titled his new bill, “To provide for the permanent location of the seat of government at Sacramento.” After its first reading on February 15th, it was sent to the Finance Committee. The Finance Committee reported out the next day that they had no recommendation on the bill. When the bill was brought up again for another reading, Catlin reiterated that the legislature could meet in the Sacramento County Court of Sessions building at 7th and J streets, and the $30,000 offer by the City of Sacramento to cover the move.

Senator Bryan questioned the legality of the Mayor or town council offering such bonds to cover the relocation expense as potentially exceeding the authority of its charter. This argument went nowhere and the bill was passed 15 to 12. Upon a motion to reconsider the vote, other Senators called into question the title of the bill. Senator Crabb wanted to strike out Sacramento and insert “’’capital of the State.” Another amendment called for changing the title to “…seat of government in San Jose.”

Catlin Calls For Point of Order!

As the motion to reconsider was devolving into a web of procedural votes and amendments, all designed to stymie the bill, Catlin called out for a point of order. Once he had the floor, Catlin explained that no amendment could be offered changing the title that might lead to a change of the subject matter of the bill since the Senate had already approved it. The Chair of the Senate sustained Catlin’s point of order. The motion to reconsider failed. Catlin then offered a resolution that the Secretary of the Senate be instructed to report the bill to the Assembly immediately.

The foes of a Sacramento capital were ready in the Assembly. As in the Senate, the Assembly had a majority of members in favor of removal from Benicia. The strategy was to make the bill unpalatable with amendments in either the Assembly or Senate. One amendment was to discontinue legislative per diems while the respective houses were being moved. Another amendment substituted Marysville for Sacramento as the relocation site.

When the different amendments had been offered and voted down, Assemblyman Hunter from Los Angeles resorted to bribery allegations. Hunter said he had heard from a good authority that the capital had not been moved to Sacramento earlier because Mayor Hardenbergh would not buy Judge McGowan a house for $3,000. This exploded the Assembly into a flurry of disbelief and recriminations. Assemblyman Conness, born in Ireland and later selected as a U. S. Senator in 1863, objected to the insinuation without evidence.

Assemblyman Hunter continued that the constant interruptions of a certain gentleman reminded him of the Irishman’s fly that was in everybody’s dish. Hunter was chastised for his bigoted remarks pertaining to a person’s nationality. The San Francisco representatives were particularly irked. Assemblyman Bradford surmised that any man who left his native country of his own accord and adopted the laws and customs of the United States, was one more to be honored than one born on this soil, and was thus an American citizen by accident.

Legislators Start Work in Sacramento, March 1854

After a few more failed amendments, the bill was passed and sent to the Governor to sign. On February 25, 1854, Governor Bigler signed the bill to permanently move California’s capital from Benicia to Sacramento. Sacramento then rushed to get the court house in order. The California legislature held it first working session in Sacramento on March 3rd.

It was quite a battle in a short period of time for Catlin to get his legislation approved. With the State’s capital, Sacramento would become the center of political activity hosting numerous conventions throughout the 19th century. Catlin would get pushed out of the Whig Party. He migrated to the Know Nothing Party and finally became a reluctant Republican. Catlin would be elected to the Assembly in 1856.

There was a general sentiment that the capital would eventually move to Sacramento, but perhaps not as soon as March 1854. Every location had its natural hazards and for Sacramento it was flooding. The city had been working to raise the levees around the city in 1854. Of course, no one was prepared for the massive flood of 1862 that saw Governor Leland Stanford travel by rowboat in Sacramento to his inauguration. With Sacramento awash in water for months, I wonder if some Californians had second thoughts about Sacramento being christened the State’s capital?

However, by 1862 California’s government was tightly tucked into Sacramento so there was little possibly of it moving again. Catlin never left Sacramento, he moved to the city permanently in the 1860s. He would go on to become a Superior Court Judge in 1890 and died in Sacramento in 1900. In the 20th century, Sacramento saw its prominence dwarfed as the Bay Area and Southern California gained population, industry, and political influence.

Sacramento On the Map Because Of California Capital

Some people may dispute my assertion that Catlin put Sacramento on the map. I am speaking more of the enduring legacy of Sacramento as a city in the 21st century. The attributes that made Sacramento so indispensable in the 19th century have evaporated. No one travels by steamer to Sacramento to mine for gold in the foothills. The mighty railroad industrial complex was shuttered in the 1980s. Our communication system no longer depends on an interconnected system of stage coaches, telegraphs, and steam engines, which, in the 1850s, was a real selling point for Sacramento.

In 2020, if you stripped away the State Capitol and all the associated government agencies, Sacramento would look very similar to Redding, Chico, Stockton, Modesto, or Fresno, all of which are nice towns, but lacking any national identification. The Sacramento region, with the economic engine of the State’s workforce, has helped lure professional basketball, minor league baseball, and soccer teams to the area. But none of those sports team really puts Sacramento on the map. It is the dome of the capitol, facilitated by Amos P. Catlin’s legislation in 1854, that makes Sacramento visible on the national stage.

This post is part of a series on Amos P. Catlin that will be woven into a book I am writing about him. The source material was primarily from the California Digital Newspaper Collection. If you would like specific newspaper dates, please contact me and I will forward them to you. For more information on Amos P. Catlin, you can visit my webpage on him: Amos P. Catlin, Sacramento.