It was a mystery to me why there were so many documents of Theodore Judah in the Amos Catlin Collection at the California State Library. Then I read a letter Catlin composed to Theodore’s widow, Anna Judah, in 1889. This letter, and many others by Anna to Catlin, revealed not only the close relationship that Catlin had with Theodore Judah, but the enduring bitterness Anna Judah still harbored toward the Big Four of the Central Pacific Railroad.

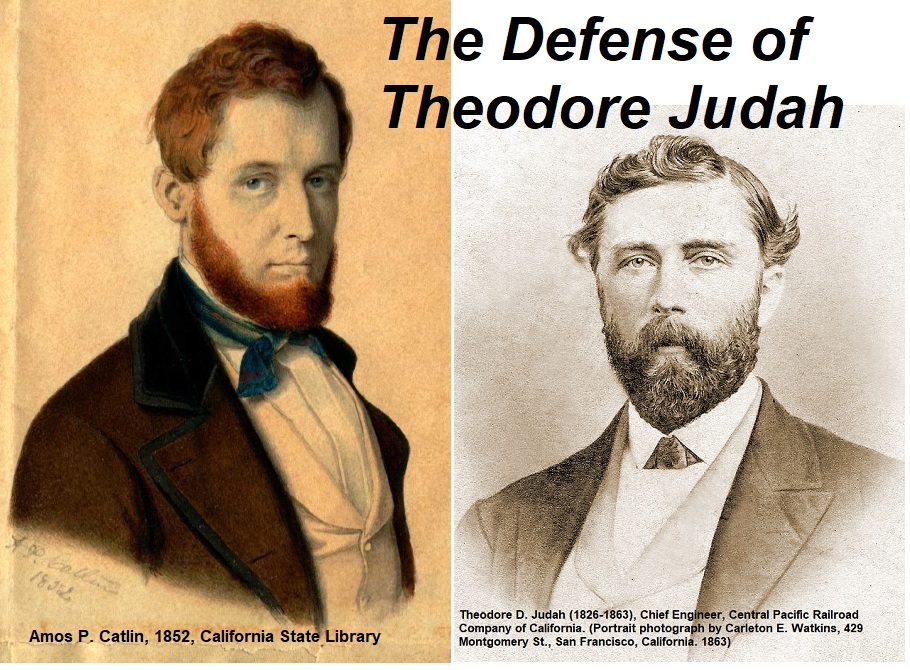

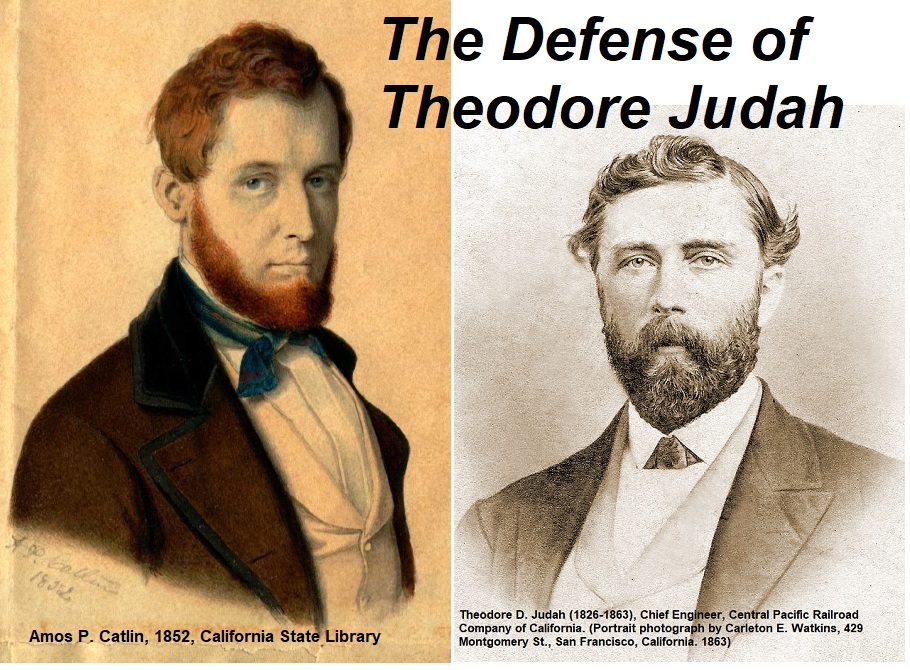

Today we recognize Theodore Judah as the motivated engineer who determined a practical rail route over the Sierra Nevada mountain range and the man, with the energy of a steam engine, who lobbied Congress to pass the act to enable the Transcontinental Railroad in 1862. Unfortunately, Judah’s perspective how the railroad fledgling railroad should be operated brought him in to conflict with the other investors of the Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR.)

Theodore Judah and the Associates

Of the original investors, corporate officers and directors, the men who have gained the most notoriety from their association with the CPRR were Leland Stanford, Charles Crocker, C. P. Huntington and Mark Hopkins. Judah, who was the Chief Engineer of CPRR, had differences of opinion regarding some aspects of construction along with management of the company. A typical request to construct it differently from Judah’s design occurred in January 1863. Charles Crocker wrote to Theodore Judah, who was Chief Engineer of the CPRR, requesting they use wooden piers for the bridge over the American River at Sacramento instead of Judah’s specified stone piers.[1]

That Judah frequently clashed with the other directors on the board of the CPRR is an understatement. But after much conflict over the building of the railroad, Judah determined that he had to find other investors to buy out the four main investors of Stanford, Crocker, Huntington, and Hopkins. Unsubstantiated rumors floated through Sacramento about an agreement between some associates and Judah that he could buy them out for $100,000 each. Regardless, Theodore and Anna journeyed to New York in October of 1863 to find new investors. Theodore contracted yellow fever and died in New York on November 2nd.

Almost immediately after the death of Judah a revisionist history began to take shape. Newspaper editorials downplayed the role Judah had in the design of the route over the Sierra’s and his role in the CPRR. Some people attributed the negative light shone upon Judah to Collis Huntington. There were those who questioned if Judah actually undertook a proper survey of the route over the Sierras. However, as the CPRR progressed up and over Donner Summit, praise and celebration was heaped on the four corporate officers, who were also positioning themselves for large profits from government subsidies and land grants. The memory of Judah was fading with each passing train.

Catlin Asks Anna Judah To Help Preserve Theodore’s Legacy

Sacramento Cal. June 9, 1889

“My Dear Mrs. Judah, a subject which has often been upon my mind, and upon which I have often intended to write to you has quite recently been renewed itself with more than usual force. History is now being made for California and much of it false. You know with what studious zeal efforts have been in a certain quarter to bury the memory of Theo. D. Judah out of sight to the future reader of the history of California. You know also how some of his friends have endeavored at times to preserve that memory.

The historian Hubert Howe Bancroft is now engaged upon that part of his great work which covers the period of Mr. Judah’s work in California, and he is particularly anxious to get reliable data in regard to Mr. Judah’s connection with the beginning of the overland RR enterprise. Mr. Bancroft has not failed to discover in a general way the real motive power which lay at the foundation of that enterprise. He wants to do justice to Mr. Judah and has applied to me for information but especially for material.”[2]

So began a long letter by Amos Catlin to Anna Judah who was living in Greenfield, Massachusetts. Catlin had dictated his own short biography to Bancroft’s “The History Company” in 1888. Of course, Theodore Judah was no longer alive to recount his involvement in the Transcontinental Railroad. Bancroft turned to Catlin because as prominent attorney in Sacramento it was known that he valued accurate historical descriptions and Catlin was more than a casual observer to the railroad developments in California.

Catlin was on the Board of Directors of the Sacramento Valley Railroad. When Col. Charles Lincoln Wilson, who originally recruited Judah to design the SVRR, started the California Central Railroad, Catlin invested money in the railroad and the town of Lincoln. Catlin was also good friends with Theodore and Anna when they lived Sacramento region. When Judah was short on cash while pursuing his Sierra Nevada surveys for the rail route, Catlin lent him money.[3] Catlin also lent Judah ten of his shares in the California Central Railroad, valued at $100 each, potentially as collateral for another loan from someone else.[4]

In Catlin’s letter to Anna he tried to be as specific as possible about learning of particular details.

“I was much chagrined with myself to find that I could not find among my papers (which are much scattered and not preserved with method) copies of Mr. Judah’s reports. I hope you have preserved them. There was one especially that I would much like to see. It was the one in which he planned the very kind of cars now called Pullman Cars…”[5]

Catlin relates to Anna that he had met with Bancroft and Bancroft asked him who he thought were the four most influential men in getting the Pacific Railroad started. Catlin named, in order of importance, 1. Judah, 2. Col. Charles L. Wilson, 3. Aaron Sargent, and 4. McDougal. Sargent and McDougal being invaluable in getting the railroad acts passed in Congress.[6]

Catlin asked Anna for specific dates regarding Judah’s trips to California, Washington, the name of the steamer they sailed on back to New York, and the object of his trip New York. He also relates information gleaned from Wilson and others that Stanford & Co. never thought a railroad could be built over the Sierras and the proposed $100,000 buyout options.[7]

“While writing I have indulged in a perusal of your letter to me dated at Erie, PA, April 9, 1865. I have often read it before with conflicting emotions of pleasure and sorrow.”[8] The sorrow that Catlin had was over the contentious settlement negotiations between the CPRR and Anna. In March of 1864, Edwin Crocker, brother of Charles Crocker and attorney for the CPRR, essentially demanded Anna turn over all of Theodore Judah’s paperwork to Collis Huntington in New York.[9]

As fellow attorneys in Sacramento, Edwin Crocker may have asked that Catlin correspond with Anna to give them Theodore Judah’s scrapbooks and other documents. Presumably, there was historical content and potentially contractual documents related to Judah’s separation with the CPRR. Aside for her enmity towards the CPRR, Anna was shrewd and knew that Crocker and Huntington would exploit Theodore’s papers against her.

Anna wrote to Catlin on April 9, 1865.

“I take up my pen to give you answer. Would that I could meet you face to face, for it seems impossible for me to write what the fullness of my heart dictates towards one who has so generously defended my husband’s good name. Sometime ago I wrote a letter of thanks to Mr. Upson and associates for an article published in the [Sacramento] Union and which I now infer was from your pen.[10] God bless you for every word you have uttered by mouth or pen in defense of your departed friend. He is gone! And the places that knew him, shall know him no more, but his works they follow him and make green his memory in all true hearts.

I have carefully considered the import of your letter and while feeling deeply grateful to you our friend, who must know, that to me the reputation of my husband is of the first earthly importance. Yet under all the circumstances feel that I cannot (such is my present impression) comply with your request as regards these letters though they would settle the right in this matter at once. Let me say to you as a friend Mr. Catlin, when the Central Pacific R. R. of California and Mr. Crocker have carried out in good faith their settlement made with my husband, and which is now my all, then will I recognize their privilege to call upon me to aid them in this controversy.

But until such settlement has been made, I must decline in any way interfering in & furnishing the evidence I have. I neither ask or desire anything but strict and impartial justice, based upon the contract I hold, from those who have been made rich by the professional skill and energy of my husband, and in whose service his days were greatly shortened, all of which I believe you know to be truth.”[11]

Anna Judah Responds With Theodore Judah Documents

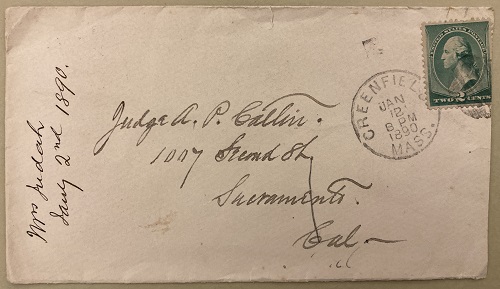

When Anna received Catlin’s 1889 letter, she responded enthusiastically. Over the next two years she would write eleven letters to Catlin and send a variety of documents, some of which reside in the Catlin Collection at the California State Library. What is apparent is that seventeen years after Theodore’s death, she can finally discuss the events of those “other days” when the Judah, Catlin, and Upson families gathered like “brothers and sisters.”

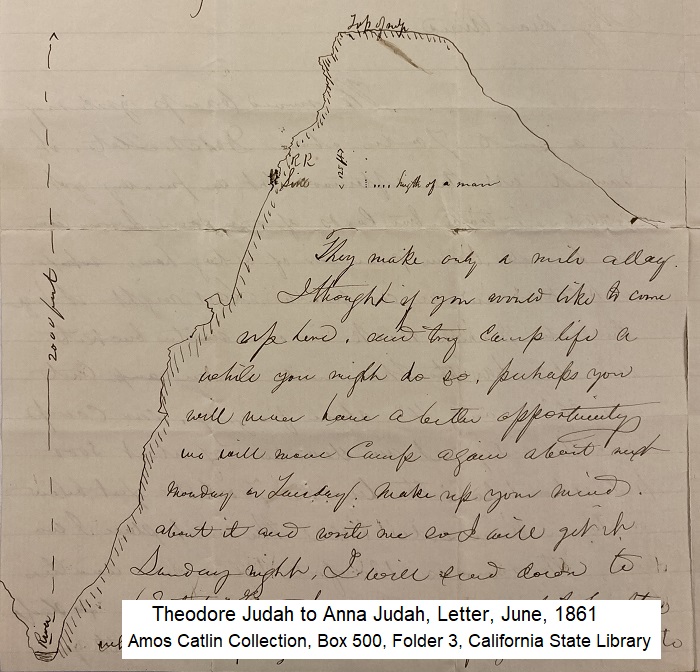

Anna forwards several letters Theodore wrote to her while he was in the Sierra’s determining the best railroad route. It is obvious that Theodore and Anna shared a deep friendship and love for one another. In Theodore’s June 13, 1861, letter to Anna, he invites her up to the mountain camp.

“I thought if you would like to come up here and try camp life a while you might do so. Perhaps you will never have a better opportunity… I will send – to Dutch Flat – myself to be there when the stage gets in. If you decide to come, let me know the day you will start and I will meet you in DF or if you choose you can come up Sunday…In case you come you had better bring up only a large carpetbag. Also, a pillow, two pillow slips, two sheets and a large comfortable which can be rolled up in a bundle. Bring plenty of reading matter and a book to press flowers, and your sewing or knitting work. Also, if any of your female friends would like to take the trip with you they can.”[12]

Anna does her best to address the questions that Catlin has about Judah. After Judah’s death rumors were floated that the Judah was done with the railroad and he and Anna would be traveling to Europe. To these hurtful rumors, Anna replied to Catlin, “Mr. Judah had no more thought of leaving the “Pacific Rail Road” till it was completed, than he had of going to the jungles of Africa to live the remainder of his days.”[13]

As Anna wrote more to Catlin her hurt, disappointment, and bitterness seeped into the correspondence. She recounts a heated discussion with Collis Huntington. “One volley was this, You can do what you like with me. I must submit, but you nor your associates can never take my husband’s name from the Pacific R.R….He built his own monument and it is as lasting as the pyramids of Egypt.” Huntington replied, “You are exercised Mrs. Judah. To me other words about as feeling as much as today I did not know what I was talking about. I think he was glad to beat a retreat. I don’t know he cared one farthing. Oh, it was cruel as the grave.”[14]

As Anna notes, she was powerless and the corporate officers of the CPRR had become millionaires on her husband’s skill and dedication to the Pacific Railroad. She was forced to take 6 percent CPRR bonds, instead of 7 percent, diminishing her income. With regards to Judah’s plans in New York, all Anna would write was that Theodore was reticent to talk about his plans, even with close associates.[15]

In a March 1891 letter Anna wonders if any of the history makes any difference to the victors who get to write the story. “They could not build the road without him [Judah]. No set of men could. Dead, they [Big Four] could do all they have done…Theodore used to say it will all be useful someday when we write a history of the P. R. R. and other papers. My dear friend, I do not know that there is any use in trying to establish the facts of those days beyond what has been. Do not suppose we could for if one were to make the “R. R. Magnets” antagonistic. They would lie out of everything. They have fed on the food so long. They think (if they can consider it) that they did everything from the beginning.”

For so long it seems that Anna Judah had bottled up a lot of rage against the Big Four of the CPRR. Catlin allowed her to express her rage against the men she felt were partly responsible for her husband’s death and her limited monetary resources. Her last couple letters were softer in tone and more inquiring of Amos and his children. In August 1891, she writes Catlin and wonders if all of the papers, scrapbooks, and journals she sent were of any historical value.[16]

As Amos Catlin had been elected Sacramento Superior Court Judge in 1890, he did not have as much time to write to Anna. She valued the correspondence with Catlin and the time spent in day dreams of her time in California with her long-departed husband, Theodore. Anna Judah died in September, 1895, after she made a significant contribution to defending and preserving the legacy of her husband.

[1] Amos Catlin Collection, Box 500, Folder 6, California State Library

[2] Amos Catlin Collection, Box 500, Folder 11, California State Library

[3] Amos Catlin Collection, Box 500, Folder 16, 1859, July 18, Promissory Note for $1,600 to Catlin from Judah, California State Library.

[4] Amos Catlin Collection, Box 500, Folder 16, 1859, August 29, Note from Judah to Catlin, California State Library.

[5] Amos Catlin Collection, Box 500, Folder 11, California State Library

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Amos Catlin Collection, Box 500, Folder 8, California State Library

[10] Lauren Upson was editor of the Sacramento Daily Union until 1864. Amos Catlin worked as an editor at the Sacramento Union in 1863 and 1864.

[11] Amos Catlin Collection, Box 500, Folder 9, California State Library

[12] Amos Catlin Collection, Box 500, Folder 3, California State Library

[13] Amos Catlin Collection, Box 500, Folder 12, California State Library

[14] Ibid

[15] Ibid

[16] Ibid